In a year of declining death-penalty usage across the United States, nowhere was the erosion of capital punishment as sustained and pronounced in 2019 as it was in the western United States. Continuing a wave of momentum from Washington’s judicial abolition of capital punishment in October 2018, one state halted executions and dismantled its death chamber, another cleared its death row, two cut back on the circumstances in which the death penalty could be sought and imposed, and the entire region set record lows for new death sentences and executions.

Calling capital punishment in California — the nation’s largest death-penalty state — “by all measures, a failure,” Governor Gavin Newsom announced in March 2019 that he was imposing a moratorium on executions and closing down its execution chamber. Newsom said the state’s death penalty “has discriminated against defendants who are mentally ill, black and brown, or can’t afford expensive legal representation. It has provided no public safety benefit or value as a deterrent. It has wasted billions of taxpayer dollars. But most of all, the death penalty is absolute. It’s irreversible and irreparable in the event of human error.”

California was the fourth western state in less than a decade in which governors had halted executions, and the move set aside the threat of imminent execution for more than 700 death-row prisoners, comprising more than a quarter of the entire U.S. death-row population. California joined fellow western states Colorado, Oregon, and Washington in putting executions on hold, and Newsom expressed hope that the moratorium would be an interim step towards the goal of repealing the state’s death penalty.

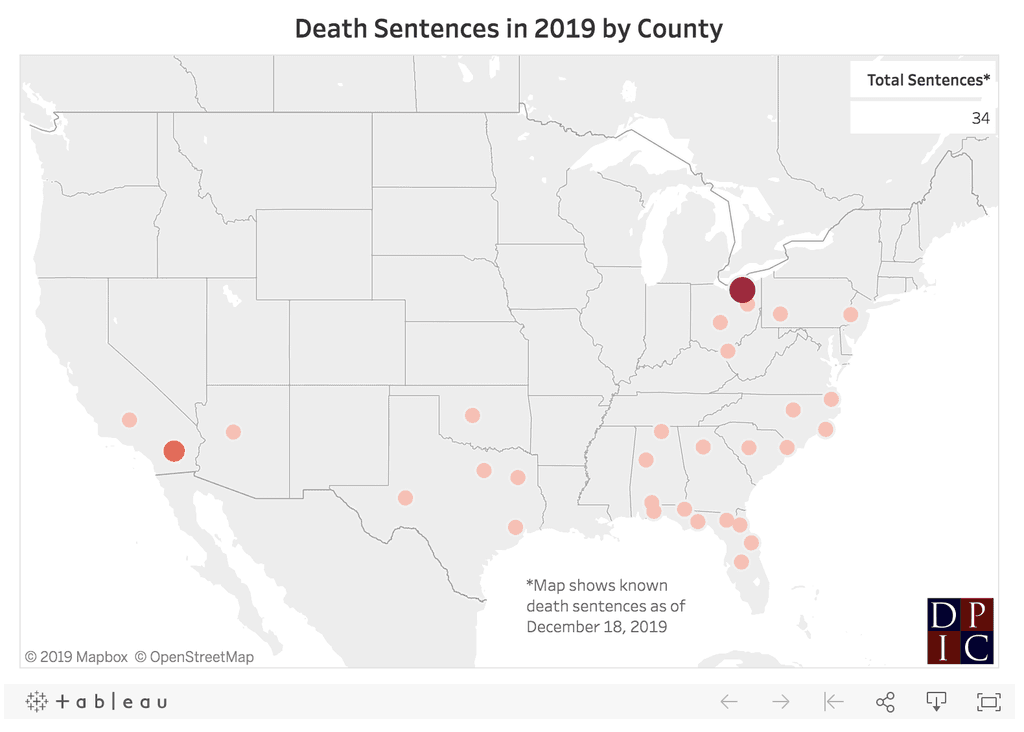

Historically, the West has accounted for fewer than 6% of executions in the United States since 1976. But executions have halted completely in the region in recent years. 2019 marked the fifth consecutive year with no executions west of Texas. Alaska, Hawaii, and New Mexico have no death penalty. California, Colorado, Montana, Nevada, and Oregon have not executed anyone in more than a decade, and will be joined by Utah in June 2020. New death sentences are also at historic lows for the region. The four new death sentences imposed in 2019 were the fewest in the West since California reinstated its death penalty in 1977, and fell by half from the prior record low set in 2018. Only three counties west of Texas sentenced anyone to death. (Click here to enlarge map.)

Courts and legislatures across the west also chipped away at the region’s use of capital punishment.

In June, the New Mexico Supreme Court cleared the state’s death row, resentencing its two remaining prisoners to life in prison a decade after the state legislature had prospectively abolished capital punishment. Relying on a state-law requirement that death sentences be proportional to punishments imposed in similar cases, the court found “no meaningful distinction” that justified the death penalty for the two prisoners still on death row as compared to “other equally horrendous cases in which defendants were not sentenced to death.”

In August, calling the state’s death penalty “dysfunctional,” “costly,” and “immoral,” Oregon Governor Kate Brown signed a bill significantly limiting the crimes for which capital punishment can be imposed in the state. The new law reduced the categories of murder punishable by death in the state from 19 to four. The death penalty now can be imposed only in cases involving acts of terrorism in which two or more people are killed, premeditated murders of children aged thirteen or younger, prison murders committed by those already incarcerated for aggravated murder, and premeditated murders of police or correctional officers.

Arizona also reduced the circumstances in which the death penalty could be imposed, eliminating death-eligibility in circumstances that had been repeatedly challenged as vague or overbroad: when the defendant “knowingly created a grave risk of death” to someone in addition to the murder victim or the murder was committed “in a cold, calculated manner without pretense of moral or legal justification.”

Abolition movements appeared to gain momentum in several state legislatures, though each effort at repeal ultimately stalled in 2019. In Wyoming, a bipartisan abolition bill passed the House and a Senate legislative committee, receiving significant Republican support in one of the country’s most conservative legislatures. The bill failed by an 18-12 vote before the full Senate but garnered the support of 1/3 of Senate Republicans. Colorado’s repeal bill failed amid criticisms that the proposal was being rushed through the legislature. Proponents vowed to try again, adopting a more conciliatory and bipartisan tone. The Intercept reports that legislative movements to repeal the death penalty are also active in Montana, Nevada, and Utah.

Sources

Death Penalty Information Center, The Death Penalty in 2019: Year End Report; DPIC databases; Liliana Segura, Jordan Smith, The Abolitionists: A Push to Repeal the Death Penalty Gains Ground Across the Western United States, The Intercept, December 3, 2019.

DPIC analysis by Robert Dunham.