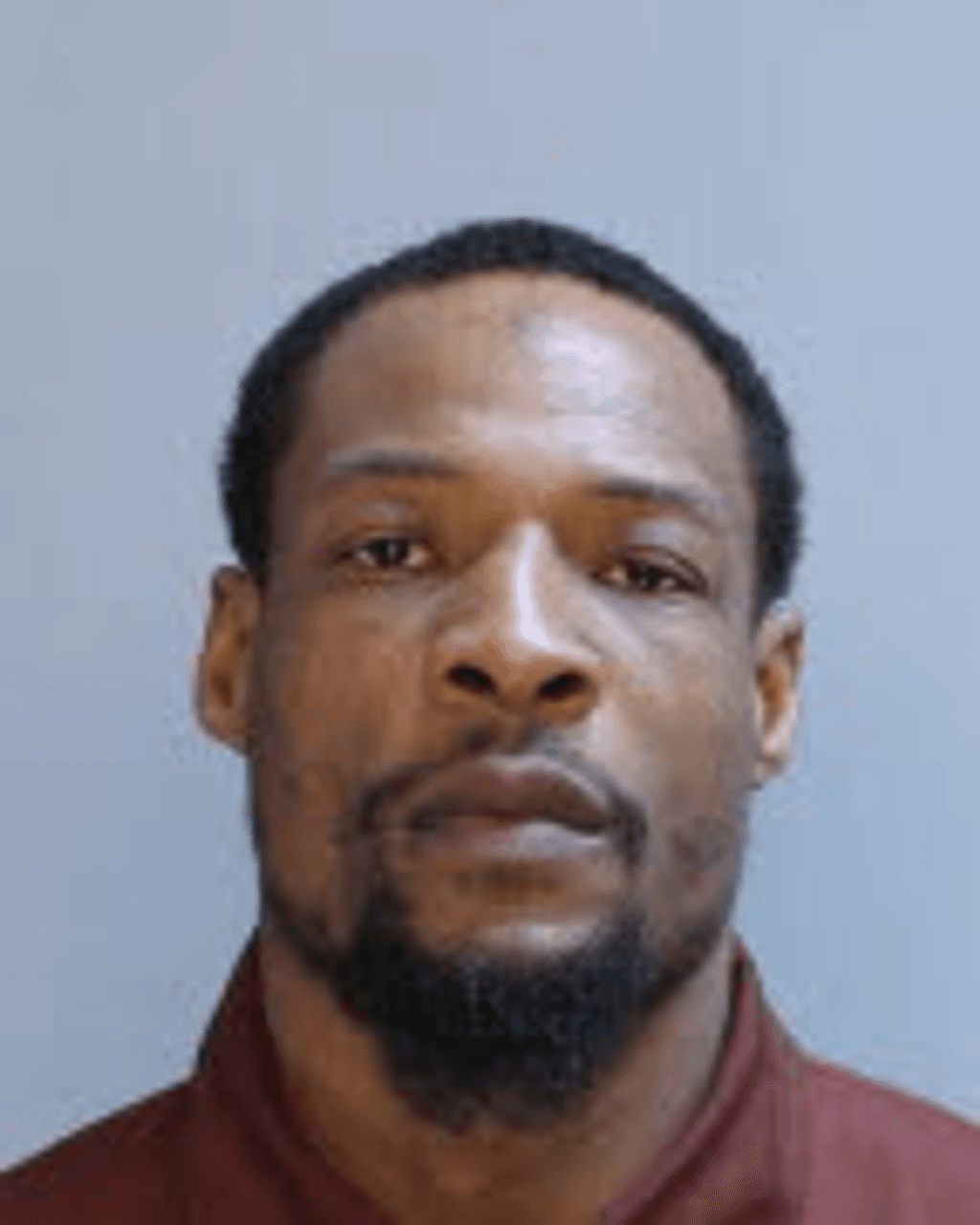

Former Pennsylvania death-row prisoner Kareem Johnson has been exonerated, thirteen years after being wrongfully convicted and sentenced to death by a Philadelphia jury. On July 1, 2020, the Philadelphia Court of Common Pleas completed his exoneration, formally entering an order dismissing all charges against him in his capital case. On May 19, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court had barred his reprosecution because of prosecutorial misconduct that exhibited a conscious and reckless disregard for his right to a fair trial .

Johnson is the third death-row exoneration in 2020 and the 170th death-row exoneration DPIC has confirmed in the United States since 1973. He is the third former Philadelphia death-row prisoner exonerated in the last six-and-one-half months. Walter Ogrod was exonerated in June 2020 and Christopher Williams was exonerated in December 2019.

Johnson’s wrongful conviction and death sentence were a product of official misconduct, false forensic evidence, and ineffective representation. He was convicted and sentenced to death in 2007 based upon evidence and argument falsely informing the jury that DNA evidence had linked him to the murder. The prosecution, police, and a prosecution forensic analyst told the jury that Johnson had shot the victim, Walter Smith, at such close range that Smith’s blood spattered onto a red baseball cap Johnson was wearing that supposedly had been recovered at the murder scene. Philadelphia homicide prosecutor Michael Barry falsely linked Johnson to the murder through the hat, telling jurors in his opening statement that it “was left at th[e] scene in the middle of the street [and] has Kareem Johnson’s sweat on it and has Walter Smith’s blood on it.”

Officer William Trenwith then testified that he had found the hat laying 8–10 feet from Smith’s body. He further told the jury that, in his years of investigating homicide, he had never seen blood travel that far a distance from a victim’s body. Based on that testimony, Barry told jurors: “We know that he [Kareem Johnson] got in real close, within 2½ feet, close enough so that Walter Smith’s blood could splash up onto the bill of the cap he was wearing.” Barry argued: “Do you know who says the killer wore the hat? Walter Smith says the killer wore the hat. He says it with his blood.”

In fact, there was no blood on the red hat, nor did the police property receipt for the hat contain any indication of blood. Smith’s blood was actually on a second hat — a black hat he was wearing at the time he was shot in the head. The DNA reports for the red hat also raised questions about the sweat stain attributed to Johnson. The initial DNA report on the sweat stain — which was supplemented twice without explanation — did not link the hat to Johnson.

When post-conviction counsel for Johnson discovered the discrepancies in the evidence, police and prosecutors claimed to have mixed up the hats. The Philadelphia DA’s office agreed that Johnson’s conviction should be overturned but stipulated to its reversal in April 2015 based only “on ineffective assistance of counsel at the guilty-innocence phase of trial.” Prosecutors insisted at the time of the stipulation that Johnson “agree[ ] to withdraw all other claims … including claims alleging prosecutorial misconduct of District Attorney Michael Barry.”

After obtaining additional discovery in preparation for retrial, Johnson moved to bar his retrial on double jeopardy grounds. Although the lower courts described the prosecution’s mishandling of the evidence in the case as “extremely negligent, perhaps even reckless” and called Johnson’s trial a “farce,” they allowed the retrial to proceed.

On May 19, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court reversed, finding that the misconduct — even if not deemed intentional — was so severe that retrying Johnson would violate his constitutional rights. “Under Article I, Section 10 of the Pennsylvania Constitution,” it wrote, “prosecutorial overreaching sufficient to invoke double jeopardy protections includes misconduct which not only deprives the defendant of his right to a fair trial, but is undertaken recklessly, that is, with a conscious disregard for a substantial risk that such will be the result.” The ruling expanded Pennsylvania’s double jeopardy protections to include cases not only of intentional misconduct, but also reckless disregard for the defendant’s right to a fair trial. Two justices dissented, saying that granting Johnson a retrial was a sufficient remedy for the prosecution’s actions.

The court returned the case to the trial court with directions to enter an order granting Johnson’s motion to bar retrial. The Philadelphia courts formally dismissed the charges on July 1.

Johnson is Pennsylvania’s ninth death-row exoneration and the sixth from Philadelphia. All six Philadelphia exonerations have involved official misconduct. Johnson remains incarcerated on unrelated murder charges. His innocence claim on those charges is pending in the Pennsylvania state courts.

Sources

Commonwealth v. Kareem Johnson, Philadelphia Court of Common Pleas case docket. Read the Pennsylvania Supreme Court’s May 19, 2020 opinion barring Johnson’s retrial.

Prosecutorial Accountability

Mar 28, 2024