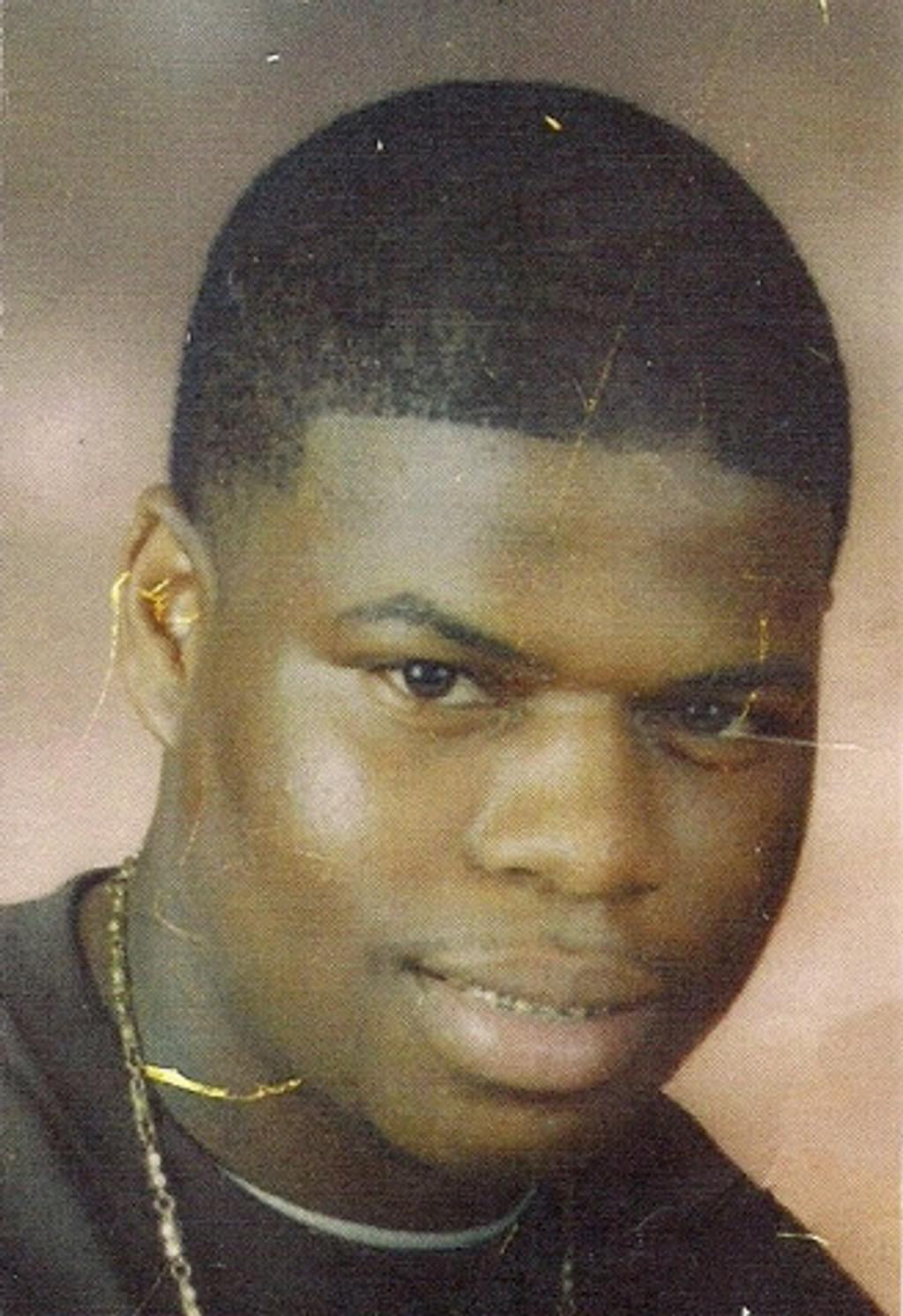

By a vote of 6-3, the U.S. Supreme Court overturned a Texas Court of Criminal Appeals (TCCA) ruling upholding the death sentence imposed on Terence Andrus (pictured). The Court held that Andrus’ counsel had provided substandard representation in the penalty-phase of his trial, and directed the TCCA to determine whether counsel’s deficient performance may have affected the jury’s sentencing decision.

The unsigned decision, issued June 15, 2020, was joined by Chief Justice John Roberts, Justice Brett Kavanaugh, and the Court’s four liberal and moderate Justices, who found that Andrus’ court-appointed lawyer had unreasonably failed to investigate “abundant” mitigating evidence that could have been presented to the jury to spare Andrus’ life. That evidence included an extensive childhood history of abuse and neglect, solitary confinement Andrus was subjected to in a juvenile facility, and a history of suicide attempts.

Andrus’ appeal lawyers presented this evidence to the Texas state courts in his state post-conviction appeals. When trial counsel provided no explanation for failing to present the evidence, the trial court declared that counsel had been ineffective and overturned Andrus’ death sentence. On appeal, the TCCA reinstated the death sentence without explanation, summarily asserting that Andrus had not met his burden of proving ineffective assistance.

In an opinion by Justice Samuel Alito, joined by Justices Clarence Thomas and Neil Gorsuch, the right wing of the Court dissented from the majority’s ruling, calling the decision “hard to take seriously.”

Andrus was sentenced to death in 2012 for shooting two people during a 2008 carjacking attempt. According to the Court’s decision, Andrus’ attorney, James “Sid” Crowley, conceded his guilt, then “informed the jury that the trial would ‘boil down to the punishment phase,’ emphasizing that ‘that’s where we are going to be fighting.’” Yet during the penalty phase, Crowley failed to rebut the state’s case that Andrus “had displayed aggressive and hostile behavior while confined in a juvenile detention center” and that he had gang affiliations. Crowley presented Andrus’ mother as a witness, who refused to reveal information about Andrus’ upbringing, including the fact that she had been addicted to drugs throughout his childhood, leaving her children alone for days or even weeks at a time, and that she had engaged in prostitution to fund her drug habit, bringing home violently abusive men. According to the Court, as a result of his mother’s behavior, “Andrus took on the role of caretaker for his four siblings” even before he reached adolescence.

The Court recounted additional mitigation that Crowley failed to present, writing that Andrus had been sent to a juvenile detention facility for having acted as a lookout while friends robbed a woman, “where, for 18 months, he was steeped in gang culture, dosed on high quantities of psychotropic drugs, and frequently relegated to extended stints of solitary confinement. The ordeal left an already traumatized Andrus all but suicidal. Those suicidal urges resurfaced later in Andrus’ adult life.” According to the six-justice majority, “[d]uring Andrus’ capital trial, however, nearly none of this mitigating evidence reached the jury. That is because Andrus’ defense counsel not only neglected to present it; he failed even to look for it.”

Andrus challenged his death sentence under Strickland v. Washington, the Supreme Court case that established the standard for determining whether a defendant received ineffective representation. Strickland sets forth a two-part test, requiring a defendant to demonstrate that counsel’s performance was deficient and that counsel’s deficiencies were prejudicial. “To show deficiency,” the Court explained, “a defendant must show that ‘counsel’s representation fell below an objective standard of reasonableness.’ And to establish prejudice, a defendant must show ‘that there is a reasonable probability that, but for counsel’s unprofessional errors, the result of the proceeding would have been different.’” The Court said “the record makes clear” that counsel’s penalty-phase representation was deficient. Because the TCCA “may have failed properly to engage with the follow-on question whether Andrus has shown that counsel’s deficient performance prejudiced him,” the Court vacated the TCCA’s judgment and returned the case to the state appeals court to consider that issue.

Justice Samuel Alito authored a strident dissent, steeped in sarcasm. The majority’s decision, Alito said, was “hard to take seriously.” The TCCA had adequately considered the Strickland standard, Alito wrote. “Perhaps the Court thinks the CCA should have used CAPITAL LETTERS or bold type. Or maybe it should have added: ‘And we really mean it!!!.’”

The U.S. Supreme Court scheduled Andrus’ case for consideration during its weekly conferences 24 times before issuing its ruling.

Sources

Jolie McCullough, U.S. Supreme Court rules Texas death row inmate had an ineffective lawyer, orders new review, Texas Tribune, June 15, 2020; Aaron Keller, Alito Flips Out as Roberts, Kavanaugh Silently Join SCOTUS Liberals in Opinion That’s ‘Hard to Take Seriously’, Law & Crime, June 15, 2020; Benjamin Wermund, U.S. Supreme Court slams defense attorney’s work in Fort Bend death penalty case, San Antonio Express-News, June 15, 2020; Anne Bloomberg, Supreme Court finds constitutionally deficient counsel in Texas death penalty case, Jurist, June 15, 2020.

Read the Supreme Court’s ruling in Andrus v. Texas.

United States Supreme Court

Apr 17, 2024

Justices Sotomayor and Jackson Issue Dissents Over Supreme Court’s Refusal to Review Two Capital Misconduct Cases

United States Supreme Court

Mar 22, 2024