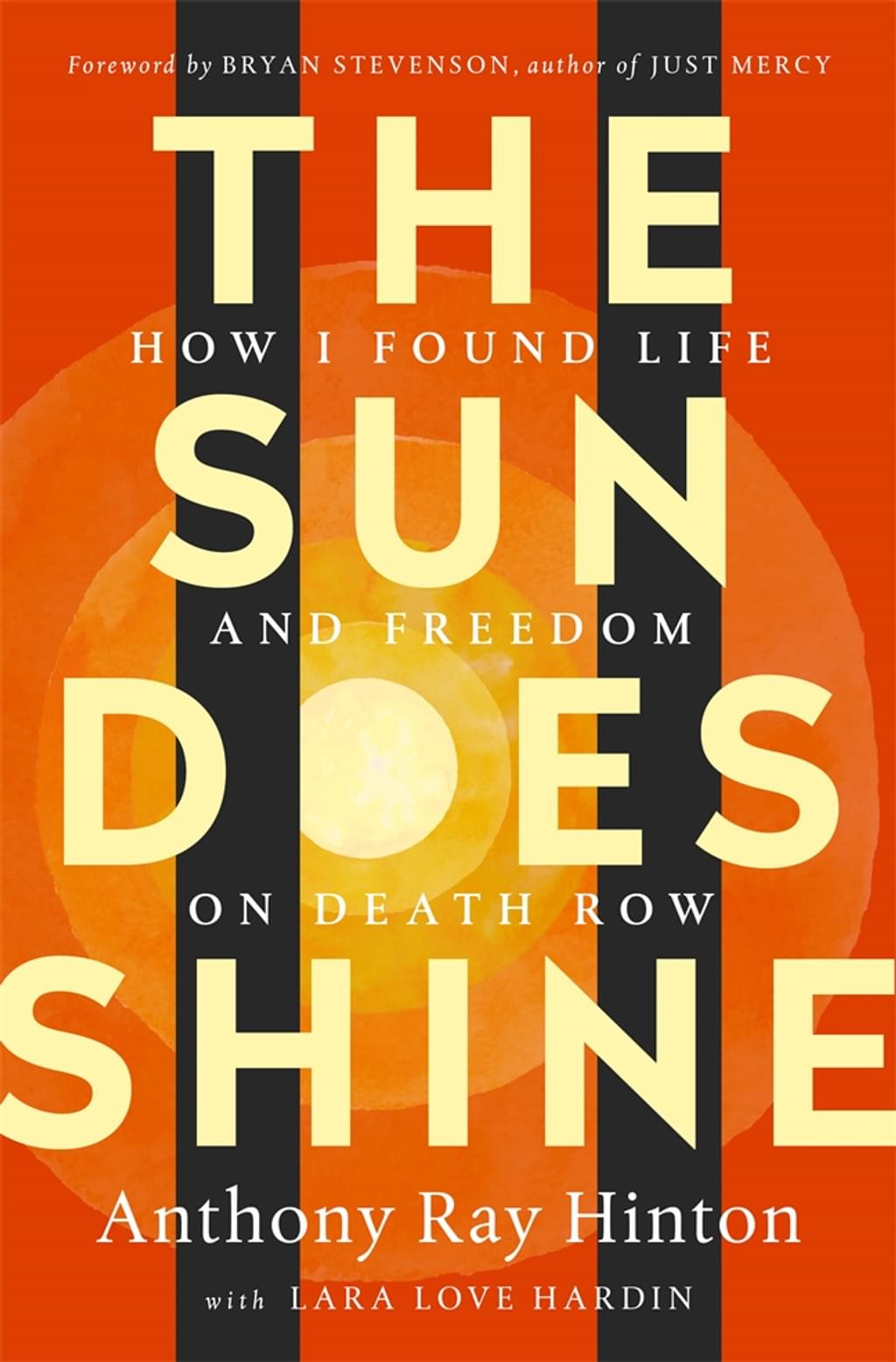

Anthony Ray Hinton spent thirty years confined on Alabama’s death row for murders he did not commit. Three years after his exoneration and release, he has published a memoir of his life, The Sun Does Shine: How I Found Life and Freedom on Death Row, that recounts stories from his childhood, the circumstances of his arrest, the travesty of his trial, how he survived and grew on death row, and how he won his freedom. The book, co-authored with Lara Love Hardin, has earned praise from Kirkus Review as an “urgent, emotional memoir from one of the longest-serving condemned death row inmates to be found innocent in America,” and “[a] heart-wrenching yet ultimately hopeful story about truth, justice, and the need for criminal justice reform.” Nobel laureate Archbishop Desmond Tutu called Hinton’s book “an amazing and heartwarming story [that] restores our faith in the inherent goodness of humanity.” The memoir begins: “There’s no way to know the exact second your life changes forever.” He was arrested in 1985 and capitally charged in connection with the murder of two fast-food restaurant managers, even though he had been working in a locked warehouse 15 miles away when that crime was committed. The prosecutor, who had a documented history of racial bias, said he could tell Hinton was guilty and “evil” just by looking at him. Hinton’s incompetent trial lawyer did not know and did not research the law, and erroneously believed the court would not provide funds to hire a qualified ballistics expert to rebut the state expert’s unsupported claim that the bullets that killed the victims had been fired from Hinton’s gun. Instead, his lawyer hired a visually impaired “expert” who did not know how to properly use a microscope, whose testimony was destroyed in front of the jury. Hinton was convicted and sentenced to death. Hinton speaks candidly about the psychological effect executions of other prisoners had on him as he feared execution for crimes he did not commit. Writing about the 1987 execution of Alabama prisoner Wayne Ritter, Hinton says, “I didn’t even realize they had executed [him] until I smelled his burned flesh.” Faced with this gruesome reality, Hinton realized, “I wasn’t ready to die. I wasn’t going to make it that easy on them.” In 2002, three top firearms examiners testified that the bullets could not be matched to Hinton’s gun, and may not have come from a single gun at all. In 2014, the U.S. Supreme Court unanimously held that Hinton had been provided substandard representation and returned his case to the state courts for further proceedings. Prosecutors decided not to retry him after the state’s new experts said they could not link the bullets to Hinton’s gun. Hinton’s lead attorney in the efforts to overturn his conviction and obtain his freedom was Bryan Stevenson, Executive Director of the Equal Justice Initiative and author of Just Mercy. In the forward to The Sun Does Shine, Stevenson writes that Hinton’s story “is situated amid racism, poverty, and an unreliable criminal justice system.” Hinton, he writes, “presents the narrative of a condemned man shaped by a painful and tortuous journey around the gates of death, who nonetheless remains hopeful, forgiving, and faithful.” Hinton—the 152nd person exonerated from America’s death rows since 1973—says he hopes his story will increase public awareness of the risks of executing the innocent and the irreparable failures of the nation’s capital-punishment system. “The death penalty is broken,” he writes, “and you are either part of the death squad or you are banging on the bars.”

(Anthony Ray Hinton, The Sun Does Shine: How I Found Life and Freedom on Death Row, St. Martin’s Press, March 2018; The Sun Does Shine: How I Found Life and Freedom on Death Row, Kirkus Reviews, December 7, 2017.) See Innocence, Race, and Representation.