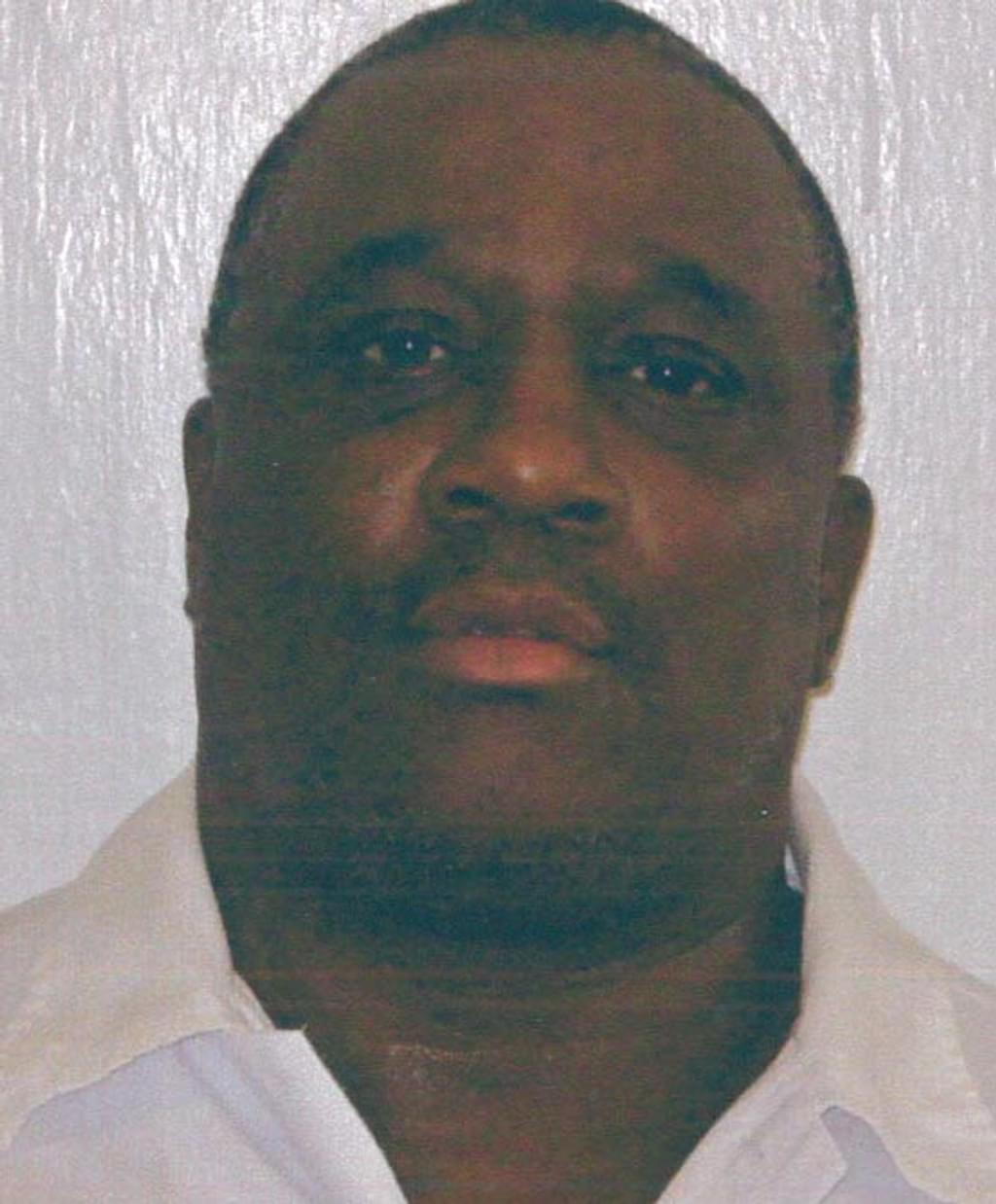

Rocky Myers (pictured) may be innocent and intellectually disabled. His jury did not think he should be sentenced to die. Alabama intends to execute him anyway. Myers’ case is rife with legal issues, but he received no federal court review because his appellate lawyer abandoned him without notice, letting the filing deadline for challenging Myers’ conviction and death sentence expire. In a recent feature story in The Nation, reporter Ashoka Mukpo tells the story of how the intellectually-disabled Myers was convicted and sentenced to death for the 1991 murder of his neighbor, Ludie Mae Tucker, even after his jury recommended 9-3 that he should be sentenced to life.

Mukpo reports that the prosecution evidence against Myers was problematic. Two informants initially told police that, on the night of the murder, another man—Anthony “Cool Breeze” Ballentine— had traded a VCR stolen from Tucker’s house for crack cocaine. Another witness corroborated their story, informing police that she had seen Ballentine, wearing a white shirt stained with blood, run into an alley near Tucker’s house. Weeks later, another man, Marzell Ewing, who had known Ballentine for 30 years, came forward to claim a reward for information about the murder. He told police he’d seen a short, stocky man near the crime scene, carrying the stolen VCR. After his statement, the original informants changed their stories, naming Myers as the man who had traded the VCR for drugs. Myers later admitted that he had found the VCR in an alley next to his house—a common drop spot for stolen goods. Because of his intellectual disability, Myers was unable to tell police when he had found the VCR, leading police to conclude he was lying. In 2004, Ewing recanted his story. In a signed statement, he revealed that a detective had offered to eliminate the record of a prior arrest if Ewing testified against Myers. Ewing’s statement admitted that his testimony was “not truthful. I did not see who brought the VCR to the shot house that night.”

Other evidence also suggested Myers is innocent. Before she died, Tucker was able to describe her assailant to the police and the clothing he was wearing. Although Tucker knew Myers, she did not identify him as her attacker. Multiple witnesses testified at Myers’ s trial that he had been wearing a dark shirt the night of the murder, not the light shirt described by Tucker. No physical evidence linked Myers to the murder and none of the fingerprints found at the crime scene matched his. Mae Puckett, one of the jurors in Myers’ case, said she and a few other jurors were not convinced of his guilt but felt pressured by the majority of the jury to vote for guilt. One white juror later spoke to Myers’ defense team, referring to him as a “thug” and describing him with a racial slur. “I never thought for a moment that he did it,” Puckett said, but she and the other jurors who doubted his guilt agreed to vote for convict if the jury would recommend a life sentence. Nonetheless, exercising a since-repealed power to override a jury’s vote for life, the trial judge sentenced Myers to death.

After Myers was sentenced to death, a Tennessee attorney, Earle J. Schwarz, agreed to represent him pro bono in his post-conviction appeals. But when the state courts denied Myers’ appeal, Schwarz never told Myers and never filed a federal habeas corpus petition, causing Myers to miss the federal filing deadline. “Mr. Schwarz decided that he could no longer represent Rocky, but unfortunately he just sat in a room and said that quietly to himself,” said Kacey Keeton, who now represented Myers. “He didn’t tell Rocky, he didn’t call the courts and let them know, he didn’t tell the prosecutors, he just quit doing anything.” On behalf of Myers, Keeton is now seeking clemency from Governor Kay Ivey, Myers’ last chance to avoid execution. “The fact that we are potentially executing a man who did not have his day in court because an attorney screwed up should give everybody pause,” Keeton said.

Studies suggest that wrongful capital convictions are more likely in cases of judicial override or non-unanimous jury votes for death. Five of Alabama’s six death row exonerations, involved either judicial override or non-unanimous jury votes for death In 2002, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the death penalty cannot be imposed on intellectually disabled defendants.

Sources

Ashoka Mukpo, Alabama Is Going to Execute Rocky Myers. He Might Be Innocent., The Nation, February 19, 2019.

See Innocence, Intellectual Disability, and Arbitrariness.

Intellectual Disability

Apr 01, 2024