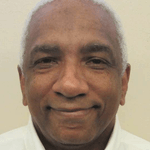

In 1986, James McWilliams (pictured), an indigent defendant, was sentenced to death by a judge in Alabama after being denied access to an independent expert who could have helped the defense understand and present his mental health issues. On April 24, 2017, the U.S. Supreme Court will hold oral argument in McWilliams v. Dunn. The question before the Court is whether, when the Supreme Court held in Ake v. Oklahoma (1985) that an indigent defendant is entitled to meaningful expert assistance for the “evaluation, preparation, and presentation of the defense,” it clearly established that the expert should be independent of the prosecution. The Brief for Petitioner (BFP) argues that “[t]he prosecution and defense can no more share the same expert than they can share the same lawyer” (BFP, p. 26).

In Ake v. Oklahoma, the U.S. Supreme Court clearly recognized that once an indigent defendant has established that his mental health is likely to be a significant factor at trial, he is entitled to receive the assistance of an expert to assist his defense. The Court in Ake recognized that “such assistance is essential to providing the defendant ‘a fair opportunity to present his defense,’ and to ensuring that facts are resolved based on the views and expertise of ‘psychiatrists for each party,’ which is consistent with the adversary system” (BFP, p. 17).

Two days before his sentencing hearing, attorneys for Mr. McWilliams, who sustained head injuries as a child and young adult, received a complex psychological report from the state’s neuropsychologist, Dr. John R. Goff. The report stated that Mr. McWilliams had “organic brain damage,” “genuine neuropsychological problems,” and “an obvious neuropsychological deficit” (BFP, p. 3), among other issues. The following day, Mr. McWilliams’s defense team received his voluminous recent mental health records, and received his prison records on the day of the sentencing. The records showed, among other things, that Mr. McWilliams was being treated with psychotropic medication. However, without the assistance of a mental health expert, attorneys for Mr. McWilliams could not review and understand the report and records regarding Mr. McWilliams’s mental impairments in time for the hearing, and without an independent expert, none of their discussions with the expert in understanding and evaluating the evidence and developing a defense strategy would be legally privileged. Mr. McWilliams’s attorneys repeatedly sought a continuance so they could consult with an independent expert and develop a mitigation case based on the evidence of Mr. McWilliams’s mental disorders and impairments. The trial court judge denied the motions and sentenced Mr. Williams to death.

Mr. McWilliams appealed his death sentence to the Alabama Court of Criminal Appeals, arguing he had been denied his constitutional right to independent expert assistance under Ake v. Oklahoma. In affirming the death sentence, the Alabama Court of Criminal Appeals held that Ake did not entitle Mr. McWilliams to anything more than the views of the psychologist who reported simultaneously to the prosecution, the defense, and the judge (BFP, p. 4). Since its decision in Mr. McWilliams’s case, the Alabama Court of Criminal Appeals has reversed itself, deciding in 2005 that Ake established a right to a mental health expert independent of the prosecution (Morris v. State).

The absence of an independent expert left Mr. McWilliams “unable to present any mitigating evidence on the only significant factor at his sentencing: his mental health” (BFP, p. 20).

The Brief for Petitioner argues that “an expert assisting the defense would have explained in lay terms to defense counsel how to present the diagnoses and information in the report and records as mitigating circumstances. Consideration of [Mr.] McWilliams’s brain damage and other mental health issues was essential to a fair and reliable sentencing determination” (BFP, p. 21).

In Ake v. Oklahoma, the U.S. Supreme Court reasoned that the right to an independent mental health expert followed from the right to counsel recognized in Gideon v. Wainwright. Underlying this case is a basic question: are poor people accused of crimes entitled to access to independent experts, just as rich people are. McWilliams v. Dunn is fundamentally about fairness, equity, and an even playing field for all in our criminal justice system.

Resources on McWilliams v. Dunn

- Brief of Petitioner James McWilliams

- Reply Brief of Petitioner James McWilliams

- James McWilliams’ Petition for a Writ of Certiorari

- Alabama’s Brief in Opposition to a Writ of Certiorari

- James McWilliams’ Reply to Brief in Opposition to a Writ of Certiorari

- Amicus Brief in Support of McWilliams from the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers, the National Association for Public Defense, National Legal Aid and Defender Association, and Twenty-Three Capital Attorneys and Investigators

- Amicus Brief in Support of McWilliams from the American Psychiatric Association, American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law, and the American Psychological Association

- Motion by two Arkansas prisoners to stay their executions, pending the outcome of McWilliams v. Dunn

- Southern Center for Human Rights resource page