Lawyers for a North Carolina capital defendant have filed a sweeping challenge to the method by which death-penalty jurors are empaneled, arguing that the combination of a process known as “death qualification” and discretionary jury strikes produces a jury so racially and sexually unrepresentative that it violates a defendant’s right to a fair trial.

Death qualification refers to the process of removing potential jurors from service in a capital case because of their expressed opposition to the death penalty. On August 16, 2022, the ACLU filed a motion on behalf of Brandon Xavier Hill (pictured), who faces the death penalty for a double murder in Wake County, North Carolina, to bar that practice. In support of that motion, Hill’s lawyers presented two days of evidence on August 29 and September 1, 2022 to Judge Paul Ridgeway, as well as the results of a Michigan State University study of jury selection in eleven Wake County capital trials between 2008 and 2019 that documented significant racial and gender disparities caused by the death-qualification process.

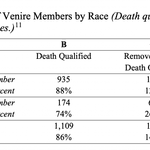

The study, conducted by law professors Catherine M. Grosso and Barbara O’Brien and updated on September 11, 2022, involved more than 1,400 prospective jurors. The researchers found statistically significant evidence of racial disparities in death qualification, with Black potential jurors removed “at 2.16 times the rate of their white counterparts.” With respect to jurors for whom no other basis for exclusion applied, they found that “Black venire members were removed on this basis at 2.27 times the rate of white venire members.”

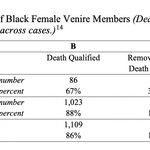

Collectively, the combination of death qualification and discretionary strikes produced two cases with no Black jurors, four with only one Black juror, and seven with no female Black jurors.

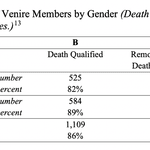

Grosso and O’Brien also found that women were deemed death unqualified at a rate that was 1.63 times greater than men were. “This disparity was driven largely by the disparate removal of Black women, who were removed under death qualification at 2.75 times the rate of other potential jurors,” they wrote in an expert report submitted to the court.

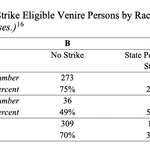

The use of discretionary peremptory strikes further diluted Black representation on death penalty juries. Grosso and O’Brien found that prosecutors “struck Black potential jurors at 2.04 times the rate it struck white venire members” with Black women excluded at 2.0 times the rate of all other jurors. “The cumulative effect of the death qualification process and the state’s exercise of peremptory strikes meant that Black potential jurors were removed at almost twice the rate of their representation in the population of potential jurors,” the researchers found. By contrast, “white potential jurors were removed at 0.8 times their rate.”

Mona Lynch, a criminology professor at University of California, Irvine, testified about the impact of death qualification on individual defendants as documented in numerous studies nationwide. “The research is very strong that Black defendants are going to suffer as a result of having disproportionate exclusion,” she told the court.

The hearing has been put on hold when one of the lawyers in the case became seriously ill. Additional evidence is expected to be presented when the hearing resumes.

‘Death Qualification’ and the Distortion of Capital Sentencing Juries

Studies have long shown that death-qualified jurors are disproportionately white and male and are more conviction-prone than other jurors. Nevertheless, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the death-qualification process in Lockhart v. McCree in 1986 against a challenge that it violated a defendant’s Sixth Amendment rights to an impartial jury drawn from a fair cross-section of the community. The Court has not revisited that decision since. Hill’s counsel present a more expansive challenge that addresses the combined impact of death qualification and discretionary strikes. They hope that the record produced in the hearing will persuade North Carolina’s courts to reconsider the permissibility of the practice under the state constitution.

The U.S. Supreme Court has said that to be constitutional under the Eighth Amendment, death-sentencing practices must reflect the evolving standards of decency that mark the progress of a maturing society. As part of that inquiry, decisions of capital sentencing juries are supposed to express the conscience of the community. Hill argues that death qualification so distorts the composition of the venire that the resulting juries are incapable of performing that constitutional function.

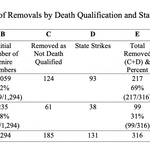

Grosso and O’Brien found that that the use of jury strikes in Wake County capital trials was disproportionate based on race and gender. Black jurors, they found, were excluded via death qualification at a significantly higher rate than white jurors. Death qualification removed 24% of Black jurors, while only 11% of white jurors were removed. 18% of women — and 33% of Black women — were excluded, while only 11% of men were removed.

The study also found statistically significant evidence that prosecutors exercised their peremptory strikes in a racially discriminatory manner. According to the researchers, prosecutors exercised their discretionary strikes to remove 51% of eligible Black jurors compared to 25% of eligible white jurors.

Grosso and O’Brien found that the combined impact of death qualification and peremptory significantly distorted the racial composition of the venire. Although Black jurors constituted 18% of the initial jury pool, they accounted for 31% of all removals. By contrast, white jurors constituted 82% of the initial venire and 69% of all removals. The combined strikes removed 42% of prospective Black jurors, compared to 20% of white jurors.

[Note: the text and images have been updated to report the results of the revised Wake County jury study, dated September 11, 2022, which included jury selection data from an additional Wake County capital trial.]

Virginia Bridges, Should North Carolina jurors against the death penalty be allowed to consider death penalty cases?, The News & Observer, September 12, 2022; In life-and-death cases, the jury box must be open to all — not just those most prone to convict, North Carolina Coalition Against the Death Penalty, August 24, 2022; Paul Brown, Death Qualified, Racist Roots, 2020; Robert Fitzgerald and Phoebe C. Ellsworth, Due Process vs. Crime Control, Law and Human Behavior, vol. 8, pp. 31 – 51 (1984).

Read the Expert Report on Wake County Jury Selection Study, revised September 11, 2022.