By Mary Beckman

www.sciencemag.org

Crime, Culpability and the Adolescent Brain

This fall, the U.S. Supreme Court will consider whether capital crimes by teenagers under 18 should get the death sentence; the case for leniency is based in part on brain studies.

When he was 17 years old, Christopher Simmons persuaded a younger friend to help him rob a woman, tie her up with electrical cable and duct tape, and throw her over a bridge. He was convicted of murder and sentenced to death by a Missouri court in 1994. In a whipsaw of legal proceedings, the Missouri Supreme Court set the sentence aside last year. Now 27, Simmons could again face execution: The state of Missouri has appealed to have the death penalty reinstated. The U.S. Supreme Court will hear the case in October, and its decision could well rest on neurobiology.

At issue is whether 16- and 17-year-olds who commit capital offenses can be executed or whether this would be cruel and unusual punishment, banned by the Constitution’s eighth amendment. In a joint brief filed on 19 July, eight medical and mental health organizations including the American Medical Association cite a sheaf of developmental biology and behavioral literature to support their argument that adolescent brains have not reached their full adult potential. “Capacities relevant to criminal responsibility are still developing when you’re 16 or 17 years old,” says psychologist Laurence Steinberg of the American Psychological Association, which joined the brief supporting Simmons. Adds physician David Fassler, spokesperson for the American Psychiatric Association (APA) and the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, the argument “does not excuse violent criminal behavior, but it’s an important factor for courts to consider” when wielding a punishment “as extreme and irreversible as death.“

The Supreme Court has addressed some of these issues before. In 1988, it held that it was unconstitutional to execute convicts under 16, but it ruled in 1989 that states were within their rights to put 16- and 17-year-old criminals to death. Thirteen years later, it decided that mentally retarded people shouldn’t be executed because they have a reduced capacity for “reasoning, judgment, and control of their impulses,” even though they generally know right from wrong (see sidebar on p. 599). That is the standard Simmons’s lawyers now want the court to extend to everyone under 18.

Cruel and unusual?

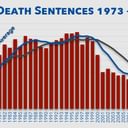

Simmons’s lawyers argue that adolescents are not as morally culpable as adults and therefore should not be subject to the death penalty. They claim that this view reflects worldwide “changing standards of decency,” a trend that has been recognized in many U.S. courts. Today, 31 states and the federal government have banned the juvenile death penalty. The latest to do so, Wyoming and South Dakota, considered brain development research in their decisions. Putting a 17-year-old to death for capital crimes is cruel and unusual punishment, according to this reasoning. “What was cruel and unusual when the Constitution was written is different from today. We don’t put people in stockades now,” says Stephen Harper, a lawyer with the Juvenile Justice Center of the American Bar Association (ABA), which also signed an amicus curiae brief. “These standards mark the progress of a civilized society.“

The defense is focusing on the “culpability of juveniles and whether their brains are as capable of impulse control, decision-making, and reasoning as adult brains are,” says law professor Steven Drizin of Northwestern University in Chicago. And some brain researchers answer with a resounding “no.” The brain’s frontal lobe, which exercises restraint over impulsive behavior, “doesn’t begin to mature until 17 years of age,” says neuroscientist Ruben Gur of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. “The very part of the brain that is judged by the legal system process comes on board late.“

But other researchers hesitate to apply scientists’ opinions to settle moral and legal questions. Although brain research should probably take a part in policy debate, it’s damaging to use science to support essentially moral stances, says neuroscientist Paul Thompson of the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA).

Shades of gray

Structurally, the brain is still growing and maturing during adolescence, beginning its final push around 16 or 17, many brain-imaging researchers agree. Some say that growth maxes out at age 20. Others, such as Jay Giedd of the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) in Bethesda, Maryland, consider 25 the age at which brain maturation peaks. Various types of brain scans and anatomic dissections show that as teens age, disordered-looking neuron cell bodies known as gray matter recede, and neuron projections covered in a protective fatty sheath, called white matter, take over. In 1999, Giedd and colleagues showed that just before puberty, children have a growth spurt of gray matter. This is followed by massive “pruning” in which about 1% of gray matter is pared down each year during the teen years, while the total volume of white matter ramps up. This process is thought to shape the brain’s neural connections for adulthood, based on experience.

In arguing for leniency, Simmons’s supporters cite some of the latest research that points to the immaturity of youthful brains, such as a May study of children and teens, led by NIMH’s Nitin Gogtay. The team followed 13 individuals between the ages of 4 and 21, performing magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) every 2 years to track changes in the physical structure of brain tissue. As previous research had suggested, the frontal lobes matured last. Starting from the back of the head, “we see a wave of brain change moving forward into the front of the brain like a forest fire,” says UCLA’s Thompson, a co-author. The brain changes continued up to age 21, the oldest person they examined. “It’s quite possible that the brain maturation peaks after age 21,” he adds.

The images showed a rapid conversion from gray to white matter. Thompson says that researchers debate whether teens are actually losing tissue when the gray matter disappears, trimming connections, or just coating gray matter with insulation. Imaging doesn’t provide high enough resolution to distinguish among the possibilities, he notes: “Right now we can image chunks of millions of neurons, but we can’t look at individual cells.” A type of spectroscopy that picks out N‑acetylaspartate, a chemical found only in neurons, shows promise in helping to settle the issue. In addition to growing volume, brain studies document an increase in the organization of white matter during adolescence. The joint brief cites a 1999 study by Tomás Paus of McGill University in Montreal and colleagues that used structural MRI to show that neuronal tracts connecting different regions of the brain thickened as they were coated with a protective sheath of myelin during adolescence (Science, 19 March 1999, p. 1908).

In 2002, another study revealed that these tracts gained in directionality as well. Relying on diffusion tensor MRI, which follows the direction that water travels, Vincent Schmithorst of the Children’s Hospital Medical Center in Cincinnati, Ohio, and colleagues watched the brain organize itself in 33 children and teens from age 5 to 18. During adolescence, the tracts funneled up from the spinal tract, through the brainstem, and into motor regions. Another linked the two major language areas. “The brain is getting more organized and dense with age,” Schmithorst says.

Don’t look at the light

Adults behave differently not just because they have different brain structures, according to Gur and others, but because they use the structures in a different way. A fully developed frontal lobe curbs impulses coming from other parts of the brain, Gur explains: “If you’ve been insulted, your emotional brain says, ‘Kill,’ but your frontal lobe says you’re in the middle of a cocktail party, ‘so let’s respond with a cutting remark.’ “

As it matures, the adolescent brain slowly reorganizes how it integrates information coming from the nether regions. Using functional MRI-which lights up sites in the brain that are active-combined with simple tests, neuroscientist Beatriz Luna of the University of Pittsburgh has found that the brain switches from relying heavily on local regions in childhood to more distributive and collaborative interactions among distant regions in adulthood.

One of the methods Luna uses to probe brain activity is the “antisaccade” test: a simplified model of real-life responses designed to determine how well the prefrontal cortex governs the more primitive parts of the brain. Subjects focus on a cross on a screen and are told that the cross will disappear and a light will show up. They are told not to look at the light, which is difficult because “the whole brainstem is wired to look at lights,” says Luna.

Adolescents can prevent themselves from peeking at the light, but in doing so they rely on brain regions different from those adults use. In 2001, Luna and colleagues showed that adolescents’ prefrontal cortices were considerably more active than adults’ in this test. Adults also used areas in the cerebellum important for timing and learning and brain regions that prepare for the task at hand.

These results support other evidence showing that teens’ impulse control is not on a par with adults’. In work in press in Child Development, Luna found that volunteers aged 14 years and older perform just as well on the task as adults, but they rely mainly on the frontal lobe’s prefrontal cortex, whereas adults exhibit a more complex response. “The adolescent is using slightly different brain mechanisms to achieve the goal,” says Luna.

Although the work is not cited in the brief, Luna says it clearly shows that “adolescents cannot be viewed at the same level as adults.“

Processing fear

Other studies-based on the amygdala, a brain region that processes emotions, and research on risk awareness-indicate that teenagers are more prone to erratic behavior than adults. Abigail Baird and Deborah Yurgelun-Todd of Harvard Medical School in Boston and others asked teens in a 1999 study to identify the emotion they perceive in pictures of faces. As expected, functional MRI showed that in both adolescents and adults, the amygdala burst with activity when presented with a face showing fear. But the prefrontal cortex didn’t blaze in teens as it did in adults, suggesting that emotional responses have little inhibition. In addition, the teens kept mistaking fearful expressions for anger or other emotions.

Baird, now at Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire, says that subsequent experiments showed that in teenagers the prefrontal cortex buzzes when they view expressions of people they know. Also, the children identified the correct emotion more than 95% of the time, an improvement of 20% over the previous work. The key difference between the results, says Baird, is that adolescents pay attention to things that matter to them but have difficulty interpreting images that are unfamiliar or seem remote in time. Teens shown a disco-era picture in previous studies would say, “Oh, he’s freaked out because he’s stuck in the ’70s,” she says. Teens are painfully aware of emotions, she notes.

But teens are really bad at the kind of thinking that requires looking into the future to see the results of actions, a characteristic that feeds increased risk-taking. Baird suggests: Ask someone, “How would you like to get roller skates and skate down some really big steps?” Adults know what might happen at the bottom and would be wary. But teens don’t see things the same way, because “they have trouble generating hypotheses of what might happen,” says Baird, partly because they don’t have access to the many experiences that adults do. The ability to do so emerges between 15 and 18 years of age, she theorizes in an upcoming issue of the Proceedings of the Royal Society of London.

Luna points out that the tumultuous nature of adolescent brains is normal: “This transition in adolescence is not a disease or an impairment. It’s an extremely adaptive way to make an adult.” She speculates that risk-taking and lowered inhibitions provide “experiences to prune their brains.“

With all the pruning, myelination, and reorganization, an adolescent’s brain is unstable, but performing well on tests can make teens look more mature than they are. “Yes, adolescents can look like adults. But put stressors into a system that’s already fragile, and it can easily revert to a less mature state,” Luna says.

The amicus curiae brief endorsed by the APA and others also describes the fragility of adolescence-how teens are sensitive to peer pressure and can be compromised by a less-than-pristine childhood environment. Abuse can affect how normally brains develop. “Not surprisingly, every [juvenile offender on death row] has been abused or neglected as a kid,” says ABA attorney Harper.

Biology and behavior

Although many researchers agree that the brain, especially the frontal lobe, continues to develop well into teenhood and beyond, many scientists hesitate to weigh in on the legal debate. Some, like Giedd, say the data “just aren’t there” for them to confidently testify to the moral or legal culpability of adolescents in court. Neuroscientist Elizabeth Sowell of UCLA says that too little data exist to connect behavior to brain structure, and imaging is far from being diagnostic. “We couldn’t do a scan on a kid and decide if they should be tried as an adult,” she says.

Harper says the reason for bringing in “the scientific and medical world is not to persuade the court but to inform the court.” Fassler, who staunchly opposes the juvenile death penalty, doesn’t want to predict how the case will turn out. “It will be close. I’m hopeful that the court will carefully review the scientific data and will agree with the conclusion that adolescents function in fundamentally different ways than adults.” And perhaps, advocates hope, toppling the death penalty with a scientific understanding of teenagers will spread to better ways of rehabilitating such youths.

SIDEBAR

Adolescence: Akin to Mental Retardation?

The human brain took center stage in 2002 when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled against the death penalty for mentally retarded persons. In that case (Atkins v. Virginia), six of the nine justices agreed that executing a convict with limited intellectual capacity, Daryl Atkins, would amount to cruel and unusual punishment. Instructing the state of Virginia to forgo the death penalty in such cases, Justice John Paul Stevens wrote: “Because of their disabilities in areas of reasoning, judgment, and control of their impulses, [mentally retarded persons] do not act with the level of moral culpability that characterizes the most serious adult criminal conduct.“

When the case of Christopher Simmons, who committed murder at age 17, comes before the same justices in October, says law professor Steven Drizin of Northwestern University in Chicago, defense attorneys hope to equate juvenile culpability to that of mentally retarded persons. “Juveniles function very much like the mentally retarded. The biggest similarity is their cognitive deficit. [Teens] may be highly functioning, but that doesn’t make them capable of making good decisions,” he says. Brain and behavior research supports that contention, argues Drizin, who represents the Children and Family Justice Center at Northwestern on the amicus curiae brief for Simmons. The “standard of decency” today is that teens do not deserve the same extreme punishment as adults.

The Atkins decision provides advocates with a “template” for what factors should be laid out to determine “evolving standards of decency,” says Drizin. These factors include the movement of state legislatures to raise the age limit for the death penalty to 18, jury verdicts of juvenile offenders, the international consensus is on the issue, and public opinion polls. In 2002, the court also considered the opinions of professional organizations with pertinent knowledge, which is how the brain research comes into play. Last, the justices considered evidence that the mentally retarded may be more likely to falsely confess and be wrongly convicted‑a problem that adolescents have as well.

-M.B.

Crime, Culpability and the Adolescent Brain

Related News & Developments