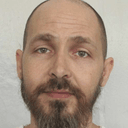

Brandon Astor Jones (pictured), the first person Georgia plans to put to death in 2016, is two weeks short of his 73rd birthday, has been on death row for 35 years, and shows signs of dementia. If his latest appeals and his application for clemency are denied, he will be the oldest person Georgia has ever executed. Jones’ case raises questions of proportionality and discriminatory application of the death penalty. He and his co-defendant Van Solomon — both African American — were sentenced to death in 1980 for killing a white gas station store clerk during a robbery. Jones denies shooting the clerk and prosecutors never determined who fired the fatal shot. His lawyers argue that the death penalty is so infrequently imposed for robbery-murders that the practice has “fallen into complete extinction.” Jones’ death sentence was initially overturned because jurors in his first trial had improperly consulted a Bible during deliberations. He was resentenced to death in the late 1990s. Solomon was executed in 1985. Stephen Bright, president of the Southern Center for Human Rights, said “We have this very strange situation now in which these people sentenced to death a long time ago — and who managed to get through all the stages of review — are now being executed.” Bright said the defendants in these “zombie case[s] … almost certainly would not be sentenced to death today.” Like Jones, all 5 inmates executed in Georgia in 2015 had been convicted at least 15 years earlier, before the establishment of the Georgia Capital Defender office. Each were provided counsel through an underfunded, ad hoc system. By contrast, no one was sentenced to death in Georgia last year. Psychologists have described Jones as exhibiting a “lifelong pattern of behavior consistent with childhood-onset bipolar disorder,” with signs of PTSD rooted in “physical, sexual, and emotional trauma” from persistent child abuse at home and in a notorious state reformatory to which he was sent as a teen.

Jones has written and published numerous essays on politics and prison life, drawing attention from penpals around the world. Many of those penpals will join Jones’ family in seeking clemency before his Feb. 2 execution date. His son, David, spoke about the impact his father’s sentence has had on their family: “I’m not oblivious to the pain that’s been created by his crime. But many lives got lost in 1979, not just one. Today, he has a lot of people who love him.”

(L. Segura, “A Life on Death Row,” The Intercept, January 31, 2016; R. Cook, “Attorneys for condemned man to plea for mercy,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, January 31, 2016.) See Arbitrariness and Upcoming Executions.