Below is an essay for our thirty-day series on John Paul Stevens by James Liebman, the Simon H. Rifkind Professor of Law at Columbia Law School. Liebman was a clerk for Justice Stevens during the 1978 Term and has since argued several capital and habeas corpus cases before the Supreme Court.

As he prepares to retire from the Supreme Court, Justice Stevens is justly being hailed for his intellect, independence, leadership, and grace. I would add another encomium: innovative legal problem solver. I don’t mean someone who looks to the law to solve social problems. I mean a judge who looks to the law to solve its own problems – someone who believes deeply in the law’s integrity but instead of assuming the law is perfect, assumes it has a capacity for self-correction.

The meaning of the Eighth Amendment as applied to the death penalty is an example of a legal problem Justice Stevens has led the Court in trying to solve. The Eighth Amendment is problematic, of course, because it obliges judges to invalidate “cruel and unusual punishments” while providing so little evidence of its meaning that it tempts judges to enforce their own, not the law’s, values. Nor are there easy fixes, such as Justice Scalia’s idea that the provision only bans punishments not authorized by statute – as if “cruel and unusual” meant “cruel and illegal” and didn’t bear at all on whether, for example, Congress or a state legislature could prescribe death as a punishment for illegal immigration.

Justice Stevens joined the Court soon after Furman v. Georgia (1972) interpreted the Eighth Amendment to bar wholly discretionary death sentencing. Every Justice wrote a separate opinion, and no two of the five in the majority agreed on the same Eighth Amendment rationale. Justices Brennan and Marshall thought the death penalty was cruel and unusual per se for different reasons. Justice Douglas found something like an equal protection violation in existing practice, given disparities by race and wealth. Justice White found more of a substantive due process violation: Capital convictions too rarely prompted death verdicts to provide a deterrent or retributive justification for state killing. Justice Stewart found a procedural due process problem: Absent standards, there was no explanation for why one person got death and another didn’t.

In five cases decided on July 2, 1976 – Gregg v. Georgia, Proffitt v. Florida, Jurek v. Texas, Woodson v. North Carolina, and Roberts v. Louisiana – Justices Stewart, Powell, and Stevens jointly authored opinions reaching three conclusions: (1) The death penalty for murder isn’t always constitutional or unconstitutional; (2) Louisiana and North Carolina could not punish all murders with death and instead had to “individualize” death sentencing; (3) on their faces, Florida, Georgia and Texas’s “guided discretion” statutes held out a prospect of constitutionally identifying murders sufficiently egregious to warrant death, but determining whether they did so in practice would require ongoing scrutiny. The remaining Justices voted either to validate or invalidate all five statutes, so the Stewart-Powell-Stevens opinions provided the only consistent basis for the mixed decisions.

By reversing the usual preference for as-applied over facial review, and by vowing to scrutinize the details of statutes and sentences to decide the constitutionality of particular capital-sentencing cases, categories and patterns, the plurality committed the Court and States to a process of cooperatively resolving remaining interpretive problems. Over the next seven years, a series of decisions in which only Justices Stevens and Stewart (when the latter was still on the Court) were consistently in the majority fleshed out this innovative approach.

In ruling that death is a cruel and unusual punishment for rape (Coker v. Georgia (1977)) and for minor participants in felonies resulting in death (Enmund v. Florida (1982)), the Court used counts of state statutes and jury verdicts to reveal the nation’s moral “going rate” for punishing those crimes. As a bulwark against substituting their own values for the moral judgment the Eighth Amendment clearly calls for but doesn’t fully define, the Justices took counsel from the aggregate conclusions of other democratic institutions. But to preserve its own duty to say what the law is, the Court treated the head count of statutes and verdicts as persuasive but not mechanically decisive. Later on, the Court used the same approach to find that death is cruel and unusual punishment for mentally retarded offenders (Atkins v. Virginia (2002)) and juveniles (Roper v. Simmons (2005)) who kill, and for the rape of a child (Kennedy v. Louisiana (2008)). In the 1980s, the Court had upheld the death penalty in the first two of these situations. But starting with Justice Stevens’ powerful decision in Atkins, the Court found that the democratically revealed moral center of gravity had shifted away from death more recently.

The harder question is how the Eighth Amendment distinguishes between murders that may and may not be punished by death. Here, the Court didn’t simply mine existing democratic judgments for evidence of the national going rate. Instead, in cases such as Lockett v. Ohio (1978) and Godfrey v. Georgia (1980), the Court read the Eighth Amendment to require new procedures through which democratic actors in each State would identify the “core” set of situations in which its citizens consistently find death to be appropriate. State legislatures had to specify aggravating factors beyond the elements of murder that mark death-eligibility. State courts had to interpret the factors objectively and narrowly. Juries had to consider all mitigating factors to be sure the killing remained at the core once aggravation was netted out by mitigation. Occasionally, the Court itself would look at individual cases and patterns of death verdicts to see if the State in fact had a meaningful basis for distinguishing death from non-death cases.

After Justice Stewart left the Court, Justice Stevens elaborated the approach. In Stevens’ view, States deserved flexibility in developing strategies for identifying the core. For example, his majority opinion for the Court in Zant v. Stephens (1983) allowed States to use narrow aggravators, a broad invitation for “mercy,” and appellate review of sentencing patterns to be certain that capital verdicts cluster at a discernable core and to overturn outliers. In a separate opinion respecting the denial of certiorari in Smith v. North Carolina (1982), Stevens praised States that instead allowed juries to impose death only when aggravation substantially outweighed mitigation. As Stevens suggested in his dissent in McCleskey v. Kemp, discussed below, the Court could complete the process of surfacing and enforcing a democratically validated moral consensus about the murders for which death is and is not “cruel and unusual punishment” by comparing each State’s core to the others and invalidating outliers.

Starting in the late 1980s, however, a changing majority of the Court backed away from this jurisprudence. With Justice Stevens in dissent, the Court approved aggravating factors that hardly narrow at all (Walton v. Arizona (1990); Payne v. Tennessee (1991)), refused to determine if States consistently apply suspect aggravators (Arave v. Creech (1993)), let States limit the uses juries make of mitigation (Graham v. Collins (1993)), allowed death sentences in cases nowhere near the aggravated core, as when aggravation and mitigation are equal (Kansas v. Marsh (2006)), let states limit capital juries to strong death penalty supporters (Uttecht v. Brown (2007)), and allowed state supreme courts that had promised to review death sentencing patterns to stop doing so (Walker v. Georgia (2008)).

McCleskey v. Kemp (1987) was the decisive case. It reviewed the constitutionality of Georgia’s capital statute as applied in light of a study showing that after controlling for legitimate factors, offenders convicted of killing whites were four times more likely to receive death than killers of blacks. Justice Powell concluded for five justices that the Court had done all it could to control racially disparate death-sentencing patterns. Those that remained were the price of maintaining social order – a conclusion Justice Powell publicly regretted after he left the Court. Justice Brennan’s passionate dissent argued that racially skewed decisions to take life are too high a price to pay for any social good.

Justice Stevens’ short dissent was the swan song of the problem-solving approach. He noted that the case didn’t present tragic choices; legal devices at hand could solve the interpretive problem. The study before the Court showed that racial disparities vanished when aggravation substantially outweighed mitigation. If the Court held to its earlier insistence that States define a core set of only the worst of the worst cases, and if the Court were willing to review States’ “cores” for invalid outliers, which Georgia’s appeared to be, the Eighth Amendment would yield a democratically attested meaning that sacrificed neither social order nor fundamental principles of equality.

In Baze v. Rees (2008), the Court upheld executions by lethal injection. In a separate opinion, Justice Stevens wrote that he had changed his mind about the death penalty and now viewed it as cruel and unusual punishment in all cases for lack of sufficient justification. Stevens offered several reasons for his change of heart, but a main one was the Court’s refusal to do its part – after many States had done theirs – to surface a democratically validated national consensus through which the Eighth Amendment could identify death verdicts that were and were not cruel and unusual.

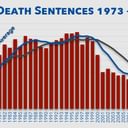

It is characteristic of Justice Stevens’ commitment to the integrity of the law and the Court that, even after concluding that the Court’s thirty-six-year effort to identify crimes for which death is an appropriate punishment had failed, he nonetheless vowed to continue applying the Court’s doctrine as best he could. It is also characteristic of Justice Stevens that, in losing the battle on the Court, his strongly reasoned view won the day in the democratic institutions to which he appealed for interpretive guidance. Since 1999, the number of death sentences imposed in the nation has dropped from three hundred to about one hundred a year, and the number of executions has declined. Even vocal pro-death-penalty prosecutors are committed to limiting the death penalty to “the worst of the worst.” One reason for the change is the gradual adoption by many jurisdictions of the narrowing steps Justice Stevens advocated.

The legal problems the death penalty and the Cruel and Unusual Punishment Clause pose are far from being solved. But by showing how a provision as problematic as the Cruel and Unusual Punishment Clause can be read to enlist other democratic actors in helping to cure its imperfections while preserving its integrity, Justice Stevens has provided a model for solving the biggest problem the Court is thought to face – the counter-majoritarian difficulty.

(E. Miller, “Justice Stevens as Legal Innovator: The Capital Cases,” SCOTUSblog, May 3 2010; posted May 14 2010).