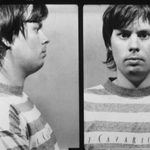

Twenty-two years after Walter Ogrod (pictured) was sentenced to death for a murder he insists he did not commit, a new Philadelphia District Attorney’s administration has dropped the office’s long-time opposition to Ogrod’s request for DNA testing and has referred the case for review by a revitalized Conviction Integrity Unit.

As that review proceeds, an hour-long documentary on the case — aired April 8 as part of CNN’s Headline News Network series Death Row Stories—presents what Philadelphia Daily News columnist Will Bunch describes as “compelling evidence that the snitch testimony that the Philadelphia District Attorney’s Office used to convict Ogrod was fabricated” and that the confession the intellectually impaired man gave to Philadelphia police was coerced. Ogrod was sentenced to death in 1996 for the high-profile 1988 murder of 4‑year-old Barbara Jean Horn, whose body was found discarded in a television box on a Northeast Philadelphia street.

No physical evidence linked Ogrod to the murder, but four years after the murder, police questioned the 25-year-old truck driver — variously described as “slow,” possibly autistic, and lacking “common sense” — for 14 hours, telling him he was repressing memories of the murder. In the documentary, a friend of Ogrod’s recounts that Ogrod signed a confession after police told him that if he didn’t, he would have to wait for a lawyer in a holding area with other prisoners and “you know what they do to child molesters down there.”

Author Tom Lowenstein, who investigated the case and wrote the 2017 book The Trials of Walter Ogrod, says in the documentary that the 16-page confession, hand written by the detective, “is a flowing monologue of thought and process and description that Walter Ogrod is not capable of…. He could not have given the confession.”

Ogrod was tried twice for the murder. In 1993, the jury in his first trial appeared to have acquitted him, filling out “not guilty” on the verdict sheet. But as the verdict was being read, one juror said he had changed his mind, resulting in a mistrial.

Following the mistrial, Ogrod was celled with John Hall, a notorious (and later discredited) jailhouse informant nicknamed “The Monsignor” for his proclivity in producing confessions. Hall’s widow, Phyllis Hall, explains in the documentary that Hall introduced Ogrod to another prisoner, Jay Wolchansky, and worked with police and prosecutors to feed Wolchansky information to implicate Ogrod in the murder. Wolchansky then testified against Ogrod in his second trial, claiming that Ogrod had confessed.

Phyllis Hall says her husband “would get some of the truth and he would sit in his cell and make up stories — and he was darned good at it.”

For years, Philadelphia’s district attorneys — first Lynne Abraham, who oversaw Ogrod’s prosecution, and later her successor, Seth Williams — fought requests from Ogrod’s lawyers to test DNA evidence that might prove his innocence. While campaigning for District Attorney in 2017, Krasner told Bunch “it is clear that for decades the practice and policy of the District Attorney’s Office has been to win convictions at any cost, too often at the cost of justice itself.”

When he took office in January 2018, Krasner rankled many entrenched prosecutors by emphasizing a reform agenda that included a willingness to take a look at questionably obtained past convictions. Krasner has not spoken about the specifics of the Ogrod case, but told Bunch, “Four-year-old Barbara Jean Horn was murdered. If the wrong person went to death row for it — and I specify that I am saying if—then the person who did murder her walked free.”

Will Bunch, Walter Ogrod’s 22-year fight to escape death row gains hope from Krasner, documentary, Philadelphia Daily News/philly.com, April 5, 2018; Death Row Stories: Walter Ogrod, Headline News Network, April 8, 2018.