On April 27, 2017, Kenneth Williams convulsed violently as he died on the gurney, the fourth prisoner put to death in an eleven-day execution spree in which Arkansas intended to execute eight men before its supply of execution drugs expired. It has not executed anyone since.

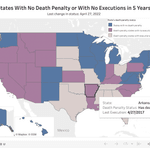

Arkansas has now gone five years without an execution, bringing to 39 the number of U.S. states that have either abolished the death penalty or not carried out an execution in five or more years. (Click to enlarge map.) Twenty-three states and the District of Columbia have abolished capital punishment. Three other states and the federal government, which collectively account for 36.4% of the nation’s death-row population, currently have moratoria on executions. An additional 10 states and the U.S. military have not carried out an execution in more than a decade, with three others not having conducted an execution since April 2017.

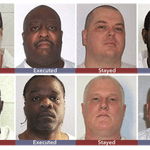

The four executions actually conducted during Arkansas’s unprecedented execution schedule were mired in controversy. The spree included the country’s first double execution in nearly 17 years, at least two of the executions were botched, and one of the people executed had serious claims of innocence that were never reviewed by Arkansas courts. Half of the executions were stayed. Three of four Black men were executed. Three of four White men were at least temporarily spared.

The execution spree, scheduled to consist of four sets of double executions, was the first time Arkansas had conducted executions since 2005. The expedited schedule was set in a rush to use the state’s supply of eight doses of midazolam before they expired at the end of April 2017.

In the period between the issuance of their death warrants and the scheduled execution dates, the eight prisoners challenged the state’s lethal injection protocol of a three-drug cocktail of midazolam, vecuronium bromide, and potassium chloride. In addition, the company that had distributed the vecuronium bromide to Arkansas sued the state, claiming that the Arkansas officials had misrepresented the intended use of the drugs. The company further alleged that Arkansas refused to return the drugs even after being offered a refund.

The prisoners’ lethal injection lawsuits and the drug company’s lawsuit were ultimately unsuccessful.

Four of the eight executions were nevertheless not carried out. Two of the prisoners, Don Davis and Bruce Ward, had been denied the assistance of an independent mental health expert at trial. The Arkansas Supreme Court stayed their executions on April 17, 2017, pending the outcome of the U.S. Supreme Court decision in McWilliams v. Dunn, which presented a similar issue. The state court also granted Ward a stay to permit his lawyers to litigate a claim that Ward was mentally incompetent to be executed. The court also issued a stay to Stacey Johnson on April 19, 2017, directing the trial court to consider his claim for DNA testing.

A federal district court stayed Jason McGehee’s execution on April 6, 2017, issuing a preliminary injunction directing the Arkansas Parole Board to comply with the state’s 30-day public notice period on the Board’s 6 – 1 recommendation to grant clemency before transmitting the recommendation to the governor. Gov. Asa Hutchinson subsequently commuted McGehee’s sentence to life without parole.

The Executions

Ledell Lee — On April 20, 2017, Arkansas executed Ledell Lee, who had made a DNA testing request that was virtually identical to Stacey Johnson’s.

In a filing to Arkansas courts before his execution, Lee sought new DNA testing of hair and blood evidence, neither of which provided conclusive results using 1995 techniques. Despite a bloody crime scene, no physical evidence had directly implicated Lee in the murder. No fingerprint evidence from the scene matched Lee and no DNA evidence was presented to the jury. Fingerprints from the crime scene did not match Lee, but Arkansas has never submitted them to a national database to determine whether they might match someone else. Hair and fingernail scrapings from the crime scene were suitable for DNA testing but had not been tested. Lee’s request for testing was denied.

Justice Josephine Linker Hart dissented from the denial of testing for Lee in light of the stay granted to Johnson. In her opinion, she wrote that she was “at a loss to explain this court’s dissimilar treatment of similarly situated litigants.”

Lee’s family continued to seek DNA testing. In January 2020, with support from the American Civil Liberties Union and the Innocence Project, they filed a state Freedom of Information Act lawsuit seeking DNA and fingerprint testing that they believed could prove his innocence.

“My family has been unable to rest for the last two and a half years, knowing that my brother was murdered by the state of Arkansas for a crime we believe he did not commit,” said Lee’s sister, Patricia Young. “What happened to Debra Reese [the victim] is horrible, and we keep her family in our prayers. But I was with Ledell the day this murder happened, and I do not see how he could have done this.”

Posthumous forensic testing found DNA from an unidentified male on the bloody club used to kill Reese and on a blood-soaked shirt that was wrapped around the weapon, raising additional troubling questions about Lee’s conviction.

Jack Jones and Marcel Williams — On April 25, 2017, Arkansas performed the only double execution of the spree. Jack Jones and Marcel Williams were put to death about three hours apart, with Williams’ execution delayed amid allegations that Jones’ execution had been botched. Williams’ lawyers filed an emergency request for a stay in federal district court, saying that “Mr. Jones’s execution appeared to be torturous and inhumane.” The state denied the allegations, calling them “utterly baseless.” According to Williams’ filing, prison staff unsuccessfully tried for 45 minutes to place a central line in Jones’ neck, before eventually placing one elsewhere on his body. Witnesses reported that corrections officials did not wait the mandated 5 minutes to perform a consciousness check on Jones, and that he was moving his lips and gulping for air after the sedative midazolam had been administered.

Kenneth Williams — The final execution was of Kenneth Williams on April 27, 2022. Media witnesses reported observing Williams “coughing, convulsing, lurching, jerking, with sound that was audible even with the microphone turned off” during his execution. Associated Press reporter Kelly Kissel said “Williams’ body jerked 15 times in quick succession — lurching violently against the leather restraint across his chest.” Kissel, who has witnessed ten executions, noted that “[t]his is the most I’ve seen an inmate move three- or four-minutes in.” Williams’ lawyer described the execution as “horrifying.” A spokesperson for the governor dismissed the witness accounts, calling the execution “flawless” and describing Williams’ movement as an “involuntary muscular reaction.”

DPIC Special Report, Background on Arkansas April 2017 Executions, Death Penalty Information Center, December 8, 2017; Press Release, ACLU, Innocence Project Demand DNA, Fingerprint Tests That Could Exonerate Ledell Lee, Executed by Arkansas in 2017, Innocence Project, January 23, 2020.

Executions Overview

Aug 28, 2023

Alabama Attorney General Seeks Execution with Unprecedented, Untested Method Using Nitrogen Hypoxia

Executions Overview

Jul 07, 2023

Missouri Governor Lifts Stay of Execution for Marcellus Williams, Ending Inquiry of Innocence Claim

Botched Executions

May 08, 2023