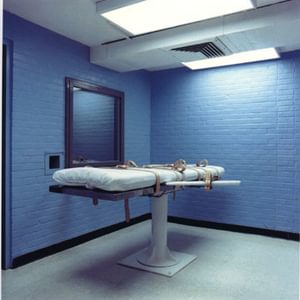

Georgia death-row prisoner Billy Daniel Raulerson, Jr. (pictured) is asking the U.S. Supreme Court to strike down a state law that, he argues, is permitting Georgia to unconstitutionally execute individuals with Intellectual Disability. On March 27, 2020, the Court is scheduled to consider whether to hear the case of Raulerson v. Warden and to review the constitutionality of Georgia’s evidentiary requirement that capital defendants prove they are intellectually disabled “beyond a reasonable doubt” before they are exempted from execution.

In 2002, in Atkins v. Virginia, the U.S. Supreme Court declared that the execution of individuals with intellectual disability violates the Eighth Amendment proscription against cruel and unusual punishment. While it has struck down several other state evidentiary rules that had resulted in the execution of some intellectually disabled offenders, it has so far declined to intervene in cases challenging Georgia’s strict burden of proving intellectual disability. In 1988, Georgia became one of the first states in the nation to prohibit the death penalty for the intellectually disabled. Yet, 32 years later, not a single defendant charged with intentional murder has been able to meet the state’s “beyond a reasonable doubt” burden of proof.

Raulerson filed his petition challenging that standard on January 24, 2020, calling Georgia’s burden of proof an “outlier” practice that no other state used in determining intellectual disability and that Georgia itself did not use in any other facet of intellectual disability law. Raulerson’s petition drew friend-of-the-court support in briefs filed by a coalition of disability rights organizations and mental disability professionals and by The Southern Center for Human Rights and the Roderick & Solange MacArthur Justice Center. Citing Cooper v. Oklahoma, a 1996 Supreme Court decision that struck down a lesser “clear and convincing evidence” standard that Oklahoma required defendants to meet for proving incompetence and Atkins’ absolute bar to executing the intellectually disabled, Raulerson asked the Court to take his case and declare Georgia’s burden of proof unconstitutional.

In Cooper, the Court held that a “procedural rule [that] allows the State to put to trial a defendant who is more likely than not incompetent” — and who therefore cannot be tried at all — violates due process. It later declared in Hall v. Florida in 2014 that “[n]o legitimate penological purpose is served by executing a person with intellectual disability.” Even worse than Cooper, Raulerson says, Georgia’s procedural rule allows the state to put to death a person who is more likely than not intellectually disabled and who, under the Atkins decision, is not eligible for the death penalty in the first place.

In a March 20 op-ed for the American Constitution Society blog, Sara Totonchi, the Southern Center’s Executive Director, provided three reasons why the time is now right for the Court to strike down Georgia’s intellectual disability standard. She writes that the Court must act because: 1) under this standard, there has not been a single finding of intellectual disability in Georgia in more than 30 years; 2) Georgia does not use such a high standard of proof for intellectual disability in any other context, such as schools or social services; and 3) both the Georgia Supreme Court and the state legislature have refused to act to change the standard.

Georgia accepts a comprehensive evaluation or medical diagnosis of intellectual disability as sufficient for individuals to qualify for educational and social services reserved for the intellectually disabled, Totonchi explains. Yet “when the stakes are the highest” in death-penalty cases, she says, Georgia evades its constitutional obligations by adopting an “unattainable standard” that, in the words of one federal appeals judge, “demands a level of certainty that medical experts simply cannot provide.”

Totonchi calls upon the Court to heed its own warning that if states are allowed “to define intellectual disability as they wished, the Court’s decision in Atkins could become a nullity, and the Eighth Amendment’s protection of human dignity would not become a reality.” She points to the case of Warren Hill, “who every expert agreed … was intellectually disabled,” as proof that Georgia has confirmed the Court’s fears. Despite the universal professional agreement that he was intellectually disabled, “Warren Hill could not prove his disability” beyond a reasonable doubt, she writes, and he was executed.

Totonchi concludes: “The state of Georgia has executed an individual with intellectual disability, and it will do so again so long as it employs its unconstitutional standard. The Court should grant certiorari in Raulerson and bring Georgia into compliance with the Constitution.”

Sara Totonchi, Georgia’s Unconstitutional Standard for Determining Intellectual Disability in Death Penalty Cases, American Constitution Society Blog, March 20, 2020.

You can read the briefs of the parties and the amicus curiae in Raulerson v. Warden here.

Disclosure: DPIC receives operational support funding from the Roderick & Solange MacArthur Justice Center. The MacArthur Justice Center had no involvement in DPIC’s editorial choice to run this story or in the content of this story.

Read Raulerson’s Petition for a Writ of Certiorari and the amicus brief of the Southern Center for Human Rights.

Intellectual Disability

Aug 02, 2024

Disability Pride Month Series: How Mitigation Specialists Help Protect Intellectually Disabled Defendants

United States Supreme Court

Jun 13, 2024

By Reversing Grants of Relief, Supreme Court Signals Lower Courts to Apply Stricter Approach to Review of Ineffective Assistance of Counsel Claims

United States Supreme Court

May 17, 2024