In a new analysis, the Death Penalty Information Center has found that executive officials most often cite disproportionate sentencing, possible innocence, and mitigation factors such as intellectual disability or mental illness as reasons to grant clemency in capital cases. Ineffective defense lawyering and official misconduct are also common factors in clemency grants. While present in fewer cases, support for clemency from the victim’s family or a decisionmaker in the original trial, such as a prosecutor or juror, appears to have a powerful impact. Prisoners frequently offer evidence of rehabilitation and remorse at clemency hearings, but this evidence is cited less often by officials.

The most common category of clemency grants was “comparative culpability/excessive sentence,” which included cases where the official felt that the prisoner had been punished more harshly than similarly culpable people, such as co-conspirators in the crime or other prisoners in the state. This factor was present in nearly 40% of cases and illustrates the unpredictability and arbitrariness of the death penalty process. Many of the prisoners received a death sentence because their co-defendant took a plea deal to testify against them, even if the co-defendant played a larger role in the crime. In at least seven cases, the prisoner had been sentenced to death even though another person killed the victim, and in nearly all of those instances the actual triggerman received a life sentence or less. For instance, Harold Glenn Williams was sentenced to death for the murder of his grandfather in 1980, while Harold’s half-brother Dennis was convicted of voluntary manslaughter and sentenced to ten years. Dennis eventually took full responsibility for the crime. After pleas from numerous people including former President Jimmy Carter, Georgia Governor Zell Miller granted Harold clemency in 1991.

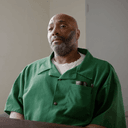

Larry Roberts, center, the 200th person exonerated from death row.

Supreme Court Chief Justice William Rehnquist once wrote that clemency is the “fail safe” of our “fallible” judicial system, providing a path to freedom when evidence emerges of a person’s innocence. Clemency review is typically the final moment that a person may be spared from execution. It is therefore unsurprising that possible innocence was one of the largest factors in an official’s decision to grant clemency, appearing in about one-third of cases. While on the one hand, this could be viewed as a sign that executives are using the clemency “fail safe” to spare the innocent in the eleventh hour, it is also a sobering reminder that these cases went through years or decades of appeals without the legal system correcting the error. In some cases, the prisoner came within hours of execution before clemency was granted. This month, Larry Roberts became the 200th person to be exonerated from death row — a significant milestone, but a fraction of the amount of people sentenced to death who have presented credible innocence claims. The 200 exonerees collectively spent 2,621 years in prison, and 70.5% of their cases involved official misconduct. Some, like Kevin Strickland in Missouri, unsuccessfully petitioned for clemency before a court found them to be innocent.

Mitigation factors, such as intellectual disability, mental illness, youth, and traumatic upbringing, also played a large role, appearing in 28% of clemency grants. Several early clemency grants aligned with later Supreme Court decisions barring the death penalty for certain groups, such as Atkins v. Virginia (2002) prohibiting the execution of people with intellectual disability and Roper v. Simmons (2005) prohibiting the execution of people who committed their crimes under the age of 18. However, in some cases after these decisions were handed down, lower courts had rejected clear evidence of a qualifying condition for exemption. For instance, in his last week in office in 2017, President Barack Obama granted clemency to Abelardo Ortiz, a Colombian man on federal death row with significant evidence of intellectual disability. Though Mr. Ortiz could not read or write in English or Spanish and had IQ scores ranging from 70 (typically seen as a benchmark for disability) to as low as 44, two federal courts had rejected his claims. Many clemency grants also noted evidence of severe mental illness that mitigated the circumstances of the crime but would not necessarily have exempted a person from execution under the Court’s convoluted precedents in that area.

Some executives appeared significantly moved by evidence of a petitioner’s traumatic childhood that had not been presented to a jury. Robert Gattis’s “family background is among the most troubling I have encountered,” wrote Delaware Governor Jack Markell in a 2012 clemency grant. Governor Markell said that the evidence of severe sexual and physical abuse “puts Mr. Gattis, his case, and his potential defenses to capital murder in an entirely different light.” Similarly, Ohio Governor John Kasich referred to Joseph Murphy’s “brutally abusive upbringing” in concluding that the death penalty was “not appropriate” for Mr. Murphy in 2011. Studies consistently find high rates of childhood abuse and poverty among people sentenced to death, and psychiatric research suggests that these early experiences profoundly shape brain development.

Ineffective representation by defense attorneys and official misconduct each appeared in about one-fifth of clemency grants. The misconduct category also included cases with irregularities in the legal process that created unfairness, such as prosecution witnesses recanting their testimony. These groups illustrated how actors in the legal system failed to ensure a fair trial and appeals process for people facing death sentences. Jeffrey Leonard’s attorney did not even know his client’s real name at trial; the attorney was later indicted for perjury for lying to a court about his record defending capital cases. Kentucky Governor Ernie Fletcher commuted Mr. Leonard’s death sentence in 2007. In 2005, Virginia Governor Mark Warner commuted the death sentence of Robin Lovitt because a state court employee destroyed physical evidence before Mr. Lovitt’s appeals were complete. The “actions of an agent of the Commonwealth, in a manner contrary to the express direction of the law, comes at the expense of a defendant facing society’s most severe and final sanction,” said Governor Warner.

We found that about half of cases (47.6%) had more than one stated or apparent reason for clemency, illustrating the compounding nature of legal violations and unfair practices in capital cases. However, this did not split evenly by category: while two-thirds of possible innocence cases had possible innocence as the only apparent reason for clemency, only one rehabilitation/remorse case out of ten had that factor as the only reason. In other words, executive officials appeared confident in citing possible innocence as the sole reason for a clemency grant, or in granting clemency when innocence was the predominant argument, but almost always relied on another justification when rehabilitation/remorse played a role in the case.

These findings suggest a possible political motive or strategic messaging to voters. In our recent Lethal Election report exploring the politicization of the death penalty, the Death Penalty Information Center found that in the past, executive officials appeared more likely to grant clemency when they did not have to face voters; in places where executives had sole authority to grant clemency, 84.6% of individual clemency grants occurred when the executive was not up for reelection. Executive officials may perceive rehabilitation/remorse as a politically “weaker” justification for clemency compared to possible innocence. (It should be noted that Lethal Election did not find any evidence that voters reacted negatively to grants of clemency in capital cases.)

Though much less common, personal pleas for clemency from decisionmakers in the original trial and victim family members appeared to hold significant sway. In their statements announcing clemency, governors quoted admissions of error by prosecutors or statements by jurors that they would have voted for life if they had more information about the defendant. In several of the cases tried before the availability of life without parole as a sentencing option, such as Jimmy Meders in Georgia, jurors said they voted for death only because life without parole was not available. Family requests held special significance when both the perpetrator and the victim had been members of the family. In Texas, Thomas Whitaker was convicted and sentenced to death for the murders of his mother and brother; his father Kent Whitaker survived a gunshot wound to the chest. Kent asked for a life sentence at the trial stage but prosecutors pursued the death penalty anyway, forcing him to continue to fight for a life sentence throughout the appeals and clemency process. “I love him, he’s my son,” Kent said. “I don’t want to see him executed at the hands of Texas in the name of justice.” Governor Greg Abbott commuted Thomas’s sentence less than an hour before the scheduled execution, his only clemency grant in a death penalty case to date.

A recent clemency hearing in Utah addressed themes of mitigation and the complicated, sometimes intersectional role of victim families. On July 22, Taberon Honie appeared before the Utah Board of Pardons & Parole to ask that his death sentence be reduced to life without parole. His execution is scheduled for August 8. Mr. Honie was convicted and sentenced to death for the 1998 murder of his girlfriend’s mother, Claudia Benn. Mr. Honie, an American Indian from the Hopi-Tewa community, was 22 years old, homeless, and extremely intoxicated on the night of the murder. “If I had been in my right mind, I would not have committed this crime,” he said.

Mr. Honie’s legal team shared evidence about his traumatic upbringing on the Hopi reservation, in a home without running water or electricity. Mr. Honie’s parents had been forced to attend Indian boarding schools, which stripped students of their cultural knowledge and used widespread abusive practices; both his parents suffered from alcoholism as adults and fought constantly, neglecting Mr. Honie and his siblings and leaving them to wander the reservation alone. Mr. Honie first tried alcohol at age 5 and experienced several serious head injuries as a child.

His daughter Tressa, who is also the granddaughter of the victim, testified in support of Mr. Honie, while other family members testified against him. Tressa said that she was “affected on both sides” and was “robbed of a grandmother.” However, she said her father had always supported her from prison and helped her through her own struggles with addiction. Mr. Honie’s attorney asked the Board to commute his death sentence so that he could continue to be present in the lives of Tressa and her daughter, Mr. Honie’s granddaughter.

Mr. Honie told the Board that he was not asking to be released — only for the right to live. “I lost any hold I had on society when I committed my crimes. I earned my place in prison. What I’m asking you today is: would you allow me to exist?”

Note: Our analysis covered all 82 grants of clemency to individual death-sentenced prisoners between 1977 – 2023, excluding mass clemency grants as those grants typically did not have case-specific rationales. We labeled cases based on the reasons the official, typically a governor, gave for granting clemency in a public statement. When the official did not offer a reason, we labeled a case based on the key elements of the individual’s clemency campaign. However, it should be noted that clemency is a complex, political process that usually involves many different claims, and it is not always possible to discern the exact claims that persuaded the official; this analysis represents our best assessment of the reasons officials relied upon to grant clemency in death penalty cases.

Jessica Miller, ‘Would you allow me to exist?’: Death row inmate pleads with Utah parole board to spare his life, The Salt Lake Tribune, July 22, 2024; Becky Bruce, Commutation hearing for Taberon Honie focuses on generational trauma, KSL News Radio, July 22, 2024; Colleen Slevin and Matthew Brown, A man facing execution for 1998 murder addresses Utah parole board, asks for life sentence instead, Associated Press, July 22, 2024; Lethal Election: How the U.S. Electoral Process Increases the Arbitrariness of the Death Penalty, Death Penalty Information Center (2024) Missouri man jailed for over 40 years exonerated; judge says he was wrongfully convicted in 3 killings, Associated Press, November 23, 2021; Luke X. Martin, Missouri Governor Does Not Pardon Kevin Strickland, Who Prosecutor Says Is Wrongfully Imprisoned, KCUR, June 3, 2021; Abelardo Arboleda Ortiz, American Bar Association Death Penalty Representation Project, June 5, 2020; Jolie McCullough, Minutes before execution, Texas Gov. Greg Abbott commutes the sentence of Thomas Whitaker, The Texas Tribune, February 22, 2018; Man who plotted his family’s murder will not be executed, governor says, ABC News, February 22, 2018; Herrera v. Collins (1992).