State & Federal

Arizona

History of the Death Penalty

Capital punishment has been a feature of the Arizona criminal justice system since 1865, when Dolores Moore became the first recorded execution in the federal territory that is now the state of Arizona. 108 executions were carried out in Arizona before the national moratorium on executions was imposed by the US Supreme Court in 1972. Executions were generally carried out by method of hanging until 1934, when the first execution by gas chamber was carried out in Arizona. Lethal injection became Arizona’s primary method of execution on November 15th of 1992, however those sentenced to death before that date may still elect lethal gas as their method of execution.

Timeline

1865 – First known execution in Arizona, Dolores Moore hung for murder.

1930 – Eva Dugan is executed and the rope snaps her head off.

1934 – Arizona abandons hanging in favor of the gas chamber for executions.

1972 – The Supreme Court strikes down the death penalty in Furman v. Georgia.

1973 – Arizona passes a law reinstating capital punishment.

1976 – The Supreme Court reinstates the death penalty when it upholds Georgia’s statute in Gregg v. Georgia.

1978 – The Supreme Court’s decision in Lockett v. Ohio invalidates Arizona’s statute. All death row prisoners were subsequently remanded for resentencing.

1979 – The Arizona Legislature revises the state’s capital punishment statute.

1992 – Arizona voters replace the gas chamber with lethal injection, although people sentenced prior to this date could still choose the gas chamber to be executed.

1999 – Arizona gasses Walter LaGrand, a German citizen, to death.

2000 – Arizona Attorney General Janet Napolitano creates the Capital Case Commission to study the death penalty in Arizona.

2001 – The International Court of Justice finds that the U.S. violated the Vienna Convention when it executed LaGrand without informing him of his right to be assisted in his case by the German consulate.

2002 – The U.S. Supreme Court finds the Arizona death penalty sentencing scheme unconstitutional in Ring v. Arizona.

2011 – Amid a national lethal injection drug shortage, the Department of Justice informs Arizona that its supply of sodium thiopental was imported illegally. Arizona rapidly switches to pentobarbital and continues executions.

2014 – Arizona executes Joseph Wood using a two-drug cocktail of midazolam and hydromorphone. It takes Wood two hours to die. A federal judge subsequently issues a stay on executions in Arizona.

2015 – Debra Milke, on death row for murdering her son, is exonerated.

2015 – Arizona tries to import illegal lethal injection drugs from India, but the drugs are confiscated at the Phoenix airport by FDA officials.

2016 — Arizona officials declare that the state does not have the drugs necessary to carry out an execution and is unable to obtain them.

2017 — A federal district court judge in Arizona denies the disclosure of execution drug suppliers to the state after Arizona’s secrecy surrounding the death penalty was challenged by multiple news organizations as violating the First Amendment.

2019 — The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit rules that the public has a First Amendment right to witness and hear the entire process of execution in First Amendment Coalition of Arizona v. Ryan. The court further prohibited Arizona from turning off the execution chamber’s microphone during an execution.

2021 — Arizona Department of Corrections, Rehabilitation, and Reentry refurbishes the state’s gas chamber and spends more than $2000 procuring cyanide gas ingredients in preparation to kill death row inmates using hydrogen cyanide. The lethal gas would be the same as that deployed at by the Nazi regime during the Holocaust.

2022 — Arizona puts Clarence Dixon to death in its first execution attempt since 2014. ADCRR personnel failed to set an intravenous line in Dixon’s arms for 25 minutes before performing an unauthorized “cutdown” procedure to use a vein in his groin to insert the IV.

2023 — Barry Jones is freed from Arizona’s death row after being incarcerated for 29 years.

Famous Cases

Tison v. Arizona: Perhaps the most infamous death penalty cases in the history of Arizona had their inception in a 1978 prison break. Gary Tison and his cellmate Randy Greenawalt, both serving life sentences for previous murders, escaped from Arizona State Prison with the help of Tison’s three sons and lackadaisical prison visitation rules. After disabling the prison’s phone and alarm system the gang fled toward the California border. After the getaway vehicle used by the group blew a tire, Gary Tison killed the family that stopped to offer assistance, taking their vehicle and fleeing towards Colorado. The group killed another couple for their vehicle in Colorado, fleeing back into Arizona. After running one roadblock set up by police, they ran into a second roadblock that was better prepared. A shootout resulted, killing one of Tison’s sons. The rest tried to escape on foot, and although Greenawalt and two of Tison’s sons were caught quickly, Gary Tison escaped into the desert. His body was discovered 11 days later. The remaining Tisons and Greenawalt were charged with 92 crimes, including several counts of capital murder, even though they had not been the ones to pull the trigger. In 1986 this issue came before the Supreme Court of the United States, with the Tison brothers arguing that Arizona’s felony murder statute was unconstitutional because it allowed for the death penalty for those other than the actual killer. In a 5 – 4 decision, the Supreme Court rejected their appeal, stating that major participants in a felony who exhibit extreme indifference to human life are eligible for the death penalty. Although Greenawalt was executed in 1997, the Tison brothers had their sentences reduced.

Ring v. Arizona: In this 2002 ruling, the Supreme Court of the United States held that jurors, rather than a judge, must be allowed to determine whether a defendant is eligible for a death sentence. The finding of the Court rested on its previous ruling in Apprendi v. New Jersey: if a particular element of the crime or sentencing factor exposed a defendant to harsher punishment, a jury must find that factor. The Supreme Court found no logical or compelling reason to exempt capital cases from this requirement. After the Supreme Court’s ruling, the Arizona legislature met in an emergency session to mend the death penalty statute to meet the guidelines laid down by the Supreme Court, providing that jurors, not judges, would be responsible for imposing a death sentence.

Notable Exonerations

On April 8, 2002, Ray Krone was released from Arizona prison after DNA evidence exonerated him. He had been convicted and sentenced to death in 1992, based on circumstantial evidence and testimony stating that bite marks on the victim’s body matched Krone’s teeth. His conviction was overturned, but he was retried and sentenced to life in prison. DNA evidence was not presented in Krone’s original trial, and tests for his second trial were inconclusive. In 2001, his defense attorney secured a court order to retest the DNA using the latest technology. Those tests found that the DNA did not belong to Krone, but instead came from another man, Kenneth Phillips, who was also in prison in Arizona.

On March 14, 2003, the Pima County Attorney’s Office dismissed all charges against death row inmate Lemuel Prion, who had been convicted of murdering Diana Vicari in 1999. In August 2002, the Arizona Supreme Court had unanimously overturned his conviction, stating that the trial court committed reversible error by excluding evidence of another suspect. According to the Supreme Court, “There was no physical evidence identifying Prion as her killer,” and the trial court abused its discretion in not allowing the defense to submit evidence that a third party, John Mazure, was the actual killer. Mazure, who was also a suspect in the murder, was known to have a violent temper, saw Vicari the night of her disappearance, concealed information from the police when they questioned him, and “appeared at work the next morning after Vicari’s disappearance so disheveled and disoriented that he was fired.” The Arizona Supreme Court held that the third-party evidence “supports the notion that Mazure had the opportunity and motive to commit this crime.” (Arizona v. Prion, No. CR-99 – 0378-AP (2002)) Prion’s conviction was based largely on the testimony of Troy Olson, who identified Prion as the man who was with Vicari on the night of her murder. However, when police first showed Olson photographs of Prion, Olson could not identify Prion. Seventeen months later, after seeing a newspaper picture of Prion labeling him as the prime suspect in the Vicari murder, Olson believed he could identify Prion. Prosecutors admitted that Prion would most likely have been acquitted if prosecuted under the standards set by the August 2002 ruling. Prion remained incarcerated in Utah for an unrelated crime.

Read DPIC’s descriptions of Arizona’s seven other exonerations:

Resources

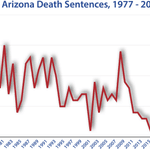

Arizona Execution Totals Since 1976

News & Developments

News

Oct 08, 2025

Upcoming Executions Illustrate Persistent Themes and Concerns Around the Death Penalty

October 9, 2025 UPDATE: On October 9, 2025, just a week before his scheduled execution, the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals (CCA) granted Robert Roberson a stay of execution and remanded his case to the district court for further consideration of his request for relief based upon relief offered in a similar case, Ex parte Roark. Like Mr. Roberson’s case, Ex parte Roark**, also involved a conviction based the now…

Read MoreNews

Jun 26, 2025

Arizona Legislature Moves Towards Compensating Exonerated Individuals, Including Eleven People Wrongfully Death Sentenced

The Arizona legislature is considering new legislation that will compensate exonerated individuals. HB 2813 was introduced in February by Republican Representative Khyl Powell and easily passed in the Arizona House of Representatives in a 59 – 1 vote two weeks later. The bill is now awaiting consideration by the Senate Judiciary and Elections Committee, and according to reporting by the Daily Independent it is being“considered for inclusion as part of a final…

Read MoreNews

Jun 17, 2025

Article of Interest: Maricopa County Investigation: Capital Cases are Costly, Lack Transparency in Charging Decisions, and Rarely End in Death Sentences

A joint investigation by ProPublica and ABC15 Arizona reviewed more than 300 cases over the past two decades where Maricopa County prosecutors sought the death penalty and found that only 13% resulted in death sentences. In most cases a jury never got close to considering whether to sentence someone to death: in more than three-quarters of cases, defendants pled guilty in exchange for lesser punishment, or prosecutors reversed course before trial. In only 41 of…

Read MoreNews

Jun 04, 2025

2025 Roundup of Death Penalty Related Legislation

More than one hundred bills have been introduced this year in 34 states and in Congress to expand and limit use of the death penalty, abolish and reinstate the death penalty, modify execution protocols and secret the information about them, and alter aspects of capital trials. Thus far, nine bills in five states have been enacted, with Florida enacting the most legislation. Of the bills that have been signed into law, three modify execution protocols; two expand…

Read MoreNews

Mar 24, 2025

Four Executions in Three Days Spotlight Constitutional Concerns About Death Penalty

In a three-day span from March 18 to March 20, four men were executed in four different states. Two of the men put to death, in Louisiana and Arizona, were the first executed in their state in years. While the close timing of the executions resulted from independent state-level decisions and individualized legal developments rather than any coordinated national effort, all four executions raised serious constitutional concerns. ### March 18: Jessie Hoffman (LA) On…

Read More