State & Federal

Pennsylvania

History of the Death Penalty

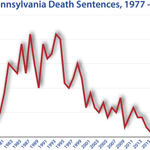

Pennsylvania began carrying out executions in the early 1600s in the form of public hangings. In 1834, Pennsylvania became the first state in the U.S. to outlaw public executions and move the gallows to county prisons. In 1913, the state’s capital punishment statute was amended to bring executions under the administration of the state rather than individual counties, and also changed the method of execution to electrocution. Between 1915 and 1962, there were 350 executions in Pennsylvania, including two women. The last prisoner executed by means of the electric chair was Elmo Smith in 1962. Pennsylvania passed a law in 1990 that changed the method of execution from electrocution to lethal injection, the current means of execution. Prior to 1976, Pennsylvania carried out 1,040 executions, the third highest number of any state. Only three executions have actually been carried out since reinstatement in 1976 despite the size of the state’s death row, which for more than two decades was the fourth largest in the nation. The Commonwealth’s death row has declined steadily in size from 246 in October 2001 to 175 in July 2016, without any executions, primarily as a result of death sentences being overturned in the courts and defendants being resentenced to life or less or acquitted. It is now the country’s fifth largest death row.

The Reading Eagle reported in June 2016 that from the time the Commonwealth enacted its current death penalty statute in September 1978 through 2015, Pennsylvania had sentenced 408 prisoners to death. Of those, 191 had subsequently been resentenced to life or less or released (46.8%), including 169 resentenced to life (41.4%); 16 resentenced to a term of years (3.9%); and 6 exonerated (1.5%). 181 remained on death row (44.4%), including 28 whose convictions or death sentences had been overturned but who were awaiting further court proceedings. 33 had died on death row other than by execution (8.1%). 3 had been executed (0.7%).

In 1931, Pennsylvania executed sixteen-year-old Alexander McClay Williams in the state’s electric chair on false charges that he had murdered Vida Robare, a white woman who served as a school matron at the youth facility to which Williams had been committed. Williams — the youngest person ever put to death in the Commonwealth — was tried, convicted, and condemned by an all-White, all-male jury in less than a day. He was executed without an appeal.

Robare had been stabbed 47 times with an ice pick and suffered two broken ribs and a skull fracture but Williams had no blood on him. Law enforcement submitted a bloody handprint from the crime scene for expert analysis but neither presented the results at trial nor disclosed them to the defense. Police never investigated Robare’s abusive ex-husband as a possible suspect even though she had recently obtained a divorce from him based on his “extreme cruelty.” After hours of police interrogation under undocumented circumstances, Williams confessed to the murder. However, the confession did not match the circumstances of the crime. A 1931 photograph shows Williams with what appears to have a black eye sustained during police interrogation.

Williams was represented at trial by William Ridley, the first African American admitted to the Bar of Delaware County, who was provided just $10 investigate and defend the case. Year’s later, Ridley’s great-grandson, Sam Lemon, and Williams’ family initiated efforts to clear his name. Lemon was able to obtain Robare’s death certificate, which listed Williams as her murderer before he even had been charged with the crime. On June 13, 2022, a judge of the Delaware County Court of Common Pleas posthumously vacated Williams’ conviction, citing “numerous fundamental due process violations.” The District Attorney’s office formally dropped charges against Williams, exonerating him 91 years after his wrongful execution.

Timeline

1834 — Pennsylvania becomes the first state to outlaw public executions and move the gallows to county prisons.

1913 — Pennsylvania’s capital punishment statute is amended to bring executions under the administration of the state rather than individual counties.

1913 — Electrocution becomes Pennsylvania’s main method of execution.

1962 — Elmo Smith becomes the last prisoner to be executed by the electric chair.

1972 — The Supreme Court of Pennsylvania rules the Commonwealth’s death penalty sentencing procedures unconstitutional. As a result, Pennsylvania’s death row was emptied and sentences were reduced to life.

1974 — Overriding Governor Shapp’s veto, the Pennsylvania legislature reenacts the death penalty, but this law is found unconstitutional in 1977.

1978 — Pennsylvania’s death penalty is reinstated when a revised version of the death penalty statute previously in place is passed.

1990 — Pennsylvania passes a law changing the method of execution from electrocution to lethal injection.

2002 — Governor Mark Schweiker signs legislation allowing prisoners access to DNA testing if it may have a bearing on the verdict in their case.

2014 — Four news organizations file suit in federal court challenging Pennsylvania’s secrecy about the source of its lethal injection drugs.

2015 — Governor Tom Wolf announces a moratorium on executions. The moratorium grants reprieves to each death row prisoner who does not receive a stay of execution from the courts.

2015 — Pennsylvania Supreme Court unanimously upholds Governor Wolf’s execution moratorium.

2017 — U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit declares Pennsylvania’s practice of keeping capital defendants in solitary confinement after courts have overturned their death sentences unconstitutional.

2020 — A federal district court judge approves a settlement that officially ends the state’s policy of mandatory permanent solitary confinement for prisoners on death row.

2023 — Governor Josh Shapiro announces that he will continue his predecessor’s moratorium on executions and calls upon the General Assembly to repeal the death penalty.

Famous Cases

Mumia Abu-Jamal was charged with the 1981 murder of police officer Daniel Faulkner and both the conviction and the subsequent death sentence sparked fierce controversy. Throughout his three-decade stay on Pennsylvania’s death row, Abu-Jamal’s supporters maintained that he is innocent. Organizations including Amnesty International and the City Government of Paris have alleged that the trial was tainted by racial discrimination and prosecutorial misconduct. While on death row, Abu-Jamal published many works, including a collection of memoirs Live From Death Row. His death sentence was overturned by a federal court as a result of an unconstitutional jury instruction in the penalty phase of his trial. That ruling was initially reversed by the U.S. Supreme Court, which directed the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit to consider the implications of a recent case it had decided. On remand, the Third Circuit again overturned Abu-Jamal’s death sentence and the Supreme Court declined to review that ruling. Maureen Faulkner (wife of Daniel Faulkner), as well as the Fraternal Order of Police, continued for many years to push for the sentence of death to be carried out. However, after the Supreme Court’s decision, she said she was willing to accept a life sentence, and the Philadelphia District Attorney agreed to withdraw the death penalty from the case. Abu-Jamal is now serving a life sentence.

Notable Exonerations

Nicholas Yarris was convicted in 1982 for the abduction, rape and murder of a young woman returning home from a day of work at the local mall. DNA evidence was collected at the crime scene but wasn’t the primary evidence in Yarris’ conviction. Multiple eyewitnesses testified to having seen a man resembling Yarris loitering in the vicinity of the shopping mall from which the victim was abducted. The prosecution also presented testimony from a prison guard and a jailhouse informant claiming that Yarris had confessed. Blood evidence was found that was the same blood type as Yarris. In 1989, Yarris sought postconviction DNA testing that was deemed inconclusive. Years later, in 2003, more sophisticated DNA testing had been developed. DNA evidence from blood on the killer’s gloves, skin under the victim’s fingernails, and semen from the victim’s panties were determined to have come a single unidentified source, who was not Nick Yarris. Yarris was released from death row, making him the 13th person exonerated from death row based on DNA evidence. The real perpetrator in the case has yet to be determined.

Ten other men have been exonerated from Pennsylvania’s death row, including six from Philadelphia, and Frederick Thomas died on the row of terminal cancer while the Philadelphia District Attorney’s office appealed a judge’s ruling that no jury would have convicted him had it known a variety of facts that were not disclosed to it at the time of trial.

Milestones in Abolition/Reinstatement

In Commonwealth v. Bradley (1972), the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania ruled the Commonwealth’s death penalty sentencing procedures unconstitutional, implementing the Supreme Court’s decision in Furman v. Georgia. Death row was emptied and sentences were judicially reduced to life. In 1974, overriding Governor Shapp’s veto, the legislature reenacted the death penalty, but this law was also found unconstitutional in 1977.

In 1978, a revised version of the death penalty statute was passed, again over Governor Shapp’s veto, reinstating the death penalty in Pennsylvania.

In 2011, the state legislature passed SR 6, initiating a study of the death penalty in Pennsylvania. The study took seven years to complete and was released in June 2018. Its numerous recommendations for reform included establishing a state-funded capital defender office, banning the death penalty for severely mentally ill defendants, and making public the details of the state’s execution protocol. None of these recommendations has been enacted.

On February 13, 2015, Governor Tom Wolf announced a moratorium on executions, citing concerns about innocence, racial bias, and the death penalty’s effects on victims’ families. Governor Wolf indicated that the moratorium would be implemented by granting reprieves to each death row prisoner who did not receive a stay of execution from the courts.

Other Interesting Facts

Pennsylvania has the most onerous clemency prerequisites of any state, requiring the five-member Board of Pardons, which includes the Attorney General, the Lt. Governor, a corrections expert, a victim advocate, and a mental health expert, to unanimously recommend clemency before the Governor has the power to consider commutation. It has not granted any death row inmate clemency since Furman v. Georgia.

Pennsylvania has an automatic death warrant statute that requires the Governor or Corrections Secretary to prematurely set execution dates at the conclusion of the direct appeal process and within 30 days of the termination of any judicial stay. This results in a series of death warrants being signed before statutorily and constitutional mandated state and federal appeals have been filed. As a result, courts have stayed more than 95% of the death warrants. Governor Wolf has refused to sign death warrants; his Secretary of Corrections has issued notices of execution.

The three prisoners executed since 1978 have all been volunteers with serious mental health issues, whom courts found to have waived their rights to an appeals process.

Resources

- American Bar Association Pennsylvania Death Penalty Assessment

- Department of Corrections

- Pennsylvanians for Alternatives to the Death Penalty

- Atlantic Center for Capital Representation

- Defender Association of Philadelphia

- Pennsylvania District Attorneys Association

- Victims’ services

- United States Court of Appeals (Third Circuit) death penalty case list

The administration of Pennsylvania death penalty has been the subject of a number of reports and analyses. You can find links to several of them below:

- The Pennsylvania Supreme Court and Third Judicial Circuit of the U.S., Report of the Joint Task Force on Death Penalty Litigation in Pennsylvania (July 1990)

- The Pennsylvania Supreme Court Committee on Racial and Gender Bias in the Justice System, Final Report of the Pennsylvania Supreme Court Committee on Racial and Gender Bias in the Justice System (2005), Chapter 5, Indigent Defense in Pennsylvania, and Chapter 6, Racial and Ethnic Disparities in the Imposition of the Death Penalty

DPIC Testimonies at Pennsylvania Legislative Hearings

Testimony before the Pennsylvania Senate Government Management and Cost Study Commission (June 7, 2010)

Testimony before the House Judiciary Committee (June 11, 2015)

Pennsylvania Execution Totals Since 1976

News & Developments

News

Jul 29, 2025

Defendants Petition the Pennsylvania Supreme Court Alleging Washington County District Attorney Abused His Discretion in Death Penalty Cases

On July 22, 2025, attorneys with the Atlantic Center for Capital Representation filed a petition on behalf of two criminal defendants — Jordan Clarke and Joshua George — alleging Washington County District Attorney Jason Walsh has demonstrated a pattern of improperly threatening or seeking death sentences in violation of the United States Constitution and the Pennsylvania Constitution. The attorneys are asking the Pennsylvania Supreme Court to use its“extraordinary…

Read MoreNews

Jun 04, 2025

2025 Roundup of Death Penalty Related Legislation

More than one hundred bills have been introduced this year in 34 states and in Congress to expand and limit use of the death penalty, abolish and reinstate the death penalty, modify execution protocols and secret the information about them, and alter aspects of capital trials. Thus far, nine bills in five states have been enacted, with Florida enacting the most legislation. Of the bills that have been signed into law, three modify execution protocols; two expand…

Read MoreNews

Mar 28, 2025

“He Looks a Little Like the Defendant”: A Closer Look at the History of Racial Bias in Jury Selection

As closing arguments of his trial began in Johnston County, North Carolina, Hasson Bacote watched as Assistant District Attorney Gregory Butler urged the jury to sentence him to death. Mr. Bacote, a Black man, had been convicted of fatally shooting 18-year-old Anthony Surles during a robbery when Mr. Bacote was just 21 years old. Mr. Bacote admitted he had fired a single shot out of a trailer, but said he did not know that he hit anyone.“Hasson Bacote is a thug: cold-blooded…

Read MoreNews

Sep 30, 2024

Rulings for Two Death-Sentenced Prisoners Recognize Devastating Harm Caused by Solitary Confinement

Scientists and other experts are unanimous in their conclusion that indefinite or prolonged solitary confinement causes serious harm, and the United Nations says it amounts to torture — yet most death-sentenced people in America are confined to these extreme conditions of isolation and deprivation for years. As of 2020, a dozen states routinely kept death-sentenced prisoners in single cells for at least twenty-two hours a day with little-to-no human contact.

Read MoreNews

Aug 30, 2024

Articles of Interest: Pittsburgh Post-Gazette Editorial Board Argues that Death Penalty Will Not Bring Justice for Leon Katz

In a new editorial, the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette argues that the death penalty is“never the justice that is called for” and achieves“nothing of value except the satisfaction of vengeance.” The Post-Gazette describes the death of 6‑week-old Leon Katz in June as an“almost unfathomable” crime and a“violation of primordial innocence” — but argues that Allegheny County District Attorney Stephen A. Zappala Jr.’s decision to seek the death penalty against…

Read More