DPIC 2021 MID-YEAR REVIEW: Virginia’s Historic Death Penalty Abolition Accompanies Continuing Record-Low Death Penalty Usage in First Half of Year

Death Penalty Decline Continues Despite Federal Execution Spree and Efforts to Bring Back Gruesome Execution Methods

Posted on Jul 01, 2021

- Introduction

- First-Half 2021 Death Sentences

- First-Half 2021 Executions

- First-Half 2021 Exonerations

- Major State and Federal Developments

Introduction Top

The first half of 2021 spotlighted two continuing death-penalty trends in the United States: the continuing erosion of capital punishment in law and practice across the country; and the extreme and often lawless conduct of the few jurisdictions that have attempted to carry out executions this year. The year began with three executions that concluded the Trump administration’s unparalleled spree of 13 federal civilian executions in six months and two days, and saw state attempts to revive gruesome, disused execution methods and to introduce never-before-tried ways of putting prisoners to death. At the same time, the first half of 2021 featured the historic abolition of capital punishment in the former home of the Confederacy and historically low numbers of both executions and new death sentences.

Virginia’s abolition of the death penalty was significant both historically and symbolically. Its repeal of capital punishment was the first time a Deep South state whose death penalty was closely tied to a history of slavery, lynching, and Jim Crow segregation had abandoned the punishment. Virginia was the 23rd state to abolish the death penalty and, with formal moratoria on executions in place in three states, meant that a majority of states either did not authorize the death penalty or had a formal policy against carrying it out.

Five people were executed in the first half of the year — three by the federal government and two by the state of Texas. Only four new death sentences were imposed, a rate of sentencing unmatched since the death penalty resumed in the U.S. in the 1970s. The low numbers were once again unquestionably affected by the pandemic, but signaled that 2021 will be the seventh consecutive year of fewer that 30 executions and fewer than 50 new death sentences in the U.S.

The states of Arizona and South Carolina moved forward with plans to carry out executions using execution methods that have been abandoned in most of the country due to their brutality. Arizona announced that it had “refurbished” its gas chamber to execute prisoners with cyanide gas, the same substance used by the Nazis to murder more than a million people during the Holocaust. One day before the tenth anniversary of the state’s last execution, the South Carolina legislature passed a law allowing the state to perform executions using the electric chair or firing squad. Alabama announced that it was nearly ready to perform executions using nitrogen hypoxia, a new, untried method in which the prisoner dies of asphyxiation from breathing pure nitrogen.

The executing states also displayed remarkable incompetence, with South Carolina setting four execution dates it was incapable of lawfully carrying out; Arizona testing the air-tightness of its execution chamber by passing a candle flame across its seals; Nevada obtaining drugs online in probable violation of state and federal law and despite advance notice that the drugs could not be used for executions; and Texas forgetting to bring assembled reporters into the prison to witness an execution.

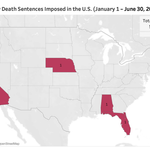

First-Half 2021 Death Sentences Top

In keeping with recent trends in the imposition of death sentences, just four people were sentenced to death in the first six months of 2021. The ongoing effects of the pandemic unquestionably contributed to this record-low number, as capital trials require lengthy preparation and significantly more extensive jury selection and may be slower to resume than other legal proceedings.

Even as the number of death sentences shrank, the few that were imposed continued to display hallmarks of systemic problems in the application of the death penalty.

- Michael Anthony Powell was sentenced to death in Alabama by a jury that voted 11 – 1 for death. Alabama is the only state that allows death sentences to be imposed when a jury does not unanimously recommend a death sentence.

- Aubrey Trail waived his right to jury sentencing and was sentenced to death in Nebraska by a three-judge panel.

- Adrian Ortiz, who was sentenced to death in California, was 19 at the time of his crime. Neuroscience experts have argued that, because the brain is not fully developed until a person’s mid-twenties, defendants under 21 should be exempt from the death penalty, just as juveniles are.

- Billy Wells, who was sentenced to death in Florida, reportedly told prosecutors that he wished to be executed.

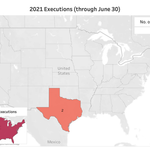

First-Half 2021 Executions Top

Executions, like death sentences, were at historic lows in the first half of 2021. Five people have been executed in the U.S. so far this year — three of them by the federal government and two by the state of Texas. As the outgoing Trump administration rushed to carry out executions, three people were executed in January 2021, less than one week before the Inauguration of President Biden, who ran on a platform of working to end the federal death penalty. The three cases that resulted in federal executions were deeply troubling.

Lisa Montgomery became the first woman executed by the federal government in the modern era of the death penalty when she was killed on January 13. More than 1,000 advocates, including current and former prosecutors, activists fighting sex trafficking and domestic violence, and mental health organizations, joined calls to halt Montgomery’s execution. Montgomery was severely mentally ill as a result of the extreme physical and sexual abuse she experienced as a child. Montgomery was relentlessly beaten, raped by her stepfather, and sexually trafficked by her mother. Four separate courts granted Montgomery stays of execution as a result of questions about her mental competency to be executed and the legality of the procedures used to set her execution date. In a series of last-minute rulings, the U.S. Supreme Court summarily vacated two of her stays of execution and denied attempts to reinstate two others. Though Montgomery’s execution notice expired at midnight on January 12, the Bureau of Prisons issued a new notice in the early hours of January 13 and executed her at 1:31 am.

The following day, the federal government executed Corey Johnson. Johnson was denied an evidentiary hearing on his claim that he was intellectually disabled and therefore ineligible for the death penalty. He was the second federal prisoner with such a claim who was executed during the federal government’s six-month execution spree. (The first was Alfred Bourgeois, executed on December 12, 2020.)

Dustin Higgs was executed on January 16. He was sentenced to death based on the testimony of a co-defendant who received a significant deal in exchange for his testimony. A third co-defendant, the undisputed triggerperson in the crime, was sentenced to life in prison. Higgs maintained that he did not orchestrate the crime, as alleged by prosecutors. The only evidence for prosecutors’ theory of the crime was the self-interested testimony of his co-defendant.

Prior to the executions, Johnson and Higgs both contracted the coronavirus during an outbreak on federal death row that was sparked by the presence of numerous outside personnel during the summer 2020 federal executions. Montgomery’s execution was stayed after her attorneys contracted the virus as a result of traveling to meet with her about her impending execution.

The federal executions were unprecedented for numerous reasons. The executions likely sparked coronavirus outbreaks not only on death row, but in the Terre Haute, Indiana community. Public health officials warned against performing executions during a global pandemic — a warning that every U.S. state observed by putting executions on hold, at least temporarily. The 13 federal executions between July 2020 and January 2021 were the most consecutive executions carried out by a single jurisdiction, and the six executions conducted following the Trump administration’s electoral defeat in November 2020 were the most executions during a presidential transition period in United States history. That spree took place at the same time the country experienced the longest period in 40 years without any state carrying out an execution, a hiatus of 315 days.

With the May 19, 2021 execution of Quintin Jones, Texas became the first state to resume executions. Jones was executed without media witnesses present, in what the Texas Department of Criminal Justice called a “miscommunication” but one state legislator characterized as “unfathomable.” It was the first time in the 571 executions carried out in Texas that media were not present.

On June 30, Texas executed John Hummel, an honorably discharged Marine who suffered from Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). Hummel had come within two days of execution in March 2020, when the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals issued a stay because of health concerns related to the COVID-19 pandemic.

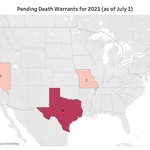

After Hummel was executed, six execution dates were pending in the U.S. for the second half of the year. Four of those are scheduled in Texas. The fifth is in Nevada, where Zane Floyd is scheduled to be executed during the week of July 26. A sixth is scheduled in Missouri, where Ernest Johnson faces execution on October 5.

Nevada has not carried out an execution since 2006 and litigation challenging the state’s execution protocol is ongoing. Noting Nevada’s delay in disclosing its never-before-used drug combination, a federal district court has issued a three-month stay of execution. The drug manufacturer Hikma Pharmaceuticals has sent the state a cease-and-desist letter demanding that its drugs be returned and accusing the state of “surreptitiously” obtaining them in violation of state and federal law.

Missouri scheduled Ernest Johnson’s execution despite strong evidence that he is intellectually disabled and therefore ineligible for the death penalty. Johnson also has epilepsy from a brain tumor, lesions, and scarring in the brain that his experts say create a substantial risk of seizures and extreme pain if he is executed by lethal injection with pentobarbital. However, the U.S. Supreme Court declined to review his challenge that Missouri’s lethal-injection process constitutes a cruel and unusual method of execution for a person with his medical condition.

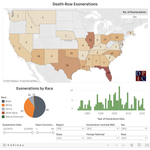

First-Half 2021 Exonerations Top

One person, Eddie Lee Howard, was exonerated from death row in the first half of 2021. Howard, who is Black, was convicted and sentenced to death in Mississippi in 1994 for the alleged rape and murder of an 84-year-old white woman. His conviction was overturned in 1997 and he was granted a new trial. At his second trial, in 2000, prosecutors presented unreliable bite-mark evidence, despite the fact that the victim’s autopsy report made no mention of bite marks. Later DNA testing excluded Howard as the source of DNA on the knife used by the murderer.

DPIC also added eleven previously unrecorded exonerations to the Exoneration List this year. While conducting research for the February 2021 report, The Innocence Epidemic, DPIC discovered eleven cases that meet the criteria for inclusion as death-row exonerations, bringing the total number of exonerations to 185. There has been one exoneration for every 8.3 executions in the modern era of the death penalty.

A federal jury verdict highlighted one of underappreciated costs of the death penalty — taxpayer liability for wrongful capital prosecutions. In a case the late Justice Antonin Scalia had touted as a justification for capital punishment, a North Carolina federal jury awarded intellectually disabled death-row exonerees Henry McCollum and Leon Brown $75 million for the police misconduct that sent them to death row.

Major State and Federal Developments Top

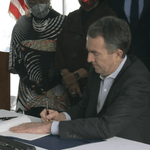

Virginia became the 23rd state to abolish the death penalty. When the three states with moratoria on executions are included, a majority of U.S. states have abandoned capital punishment. Virginia’s abolition is particularly notable, as it has executed more people in its history than any other state and is second only to Texas in executions performed in the modern era. It is also the first state in the South, and the first former Confederate state, to abolish the death penalty. Legislators and Governor Ralph Northam emphasized the racial disparities in Virginia’s use of the death penalty as a major reason for abolition.

Three states took steps to perform executions by implementing execution methods other than lethal injection. Arizona sparked international outrage when it revealed in court documents that it had spent more than $2,000 to “refurbish” its gas chamber and purchase the ingredients for cyanide gas, which was used by the Nazis to murder more than one million men, women, and children during the Holocaust. It also drew ridicule when it tested the chamber for airtightness by passing the flame of a candle slowly near the seals of the chamber.

The disclosures about Arizona’s possible use of the gas chamber came on the heels of another administrative debacle, as Department of Corrections officials spent $1.5 million to obtain lethal injection drugs. The Arizona Attorney General’s office then sought a briefing schedule to set execution dates in the Fall of 2021 based upon a representation that the drugs had a shelf life of 90 days. When, as death-row prisoners had cautioned, the shelf life turned out to be only 45 days, prosecutors responded by asking the Arizona Supreme Court to reward their mistake by shortening the briefing schedule and the time frame for judicial review so executions could go forward before the drugs expired.

South Carolina, which last carried out an execution in 2011, passed a law authorizing electrocution as the default method of execution, with lethal injection or firing squad available as alternatives. The state rapidly set two execution dates for June 2021, but the executions were stayed by the South Carolina Supreme Court, which found that attempting to execute the men by electrocution without offering them the alternative of lethal injection or firing squad violated the “statutory right of inmates to elect the manner of their execution.” It also noted that the state had not developed a protocol for executions by firing squad and barred the state from setting further execution dates until such a protocol is developed.

The two stays were not the first time in 2021 South Carolina had scheduled executions it could not lawfully carry out. The state sought to execute the same men before adopting the new law, scheduling one execution for February and another for May. However, those executions were halted for being “currently impossible” to carry out because the state lacked the drugs to do so. Directed by the court “not to issue another execution notice … until the State notifies this Court that the Department of Corrections has the ability to carry out the execution by lethal injection, that the petitioner has made an election to be electrocuted, or that there has been some change in the law which will allow the execution to take place,” prosecutors then sought a second time to carry out the executions without the proper protocols in place.

Alabama said in June 8 court filings that it “is nearing completion of the initial physical build for the nitrogen hypoxia system and its safety measures.” No state has used nitrogen hypoxia, an execution method in which the prisoner would breathe pure nitrogen, depriving his or her body of oxygen and causing asphyxiation. Its proponents argue it is a more humane method of execution, but it cannot ethically be tested. Oklahoma and Mississippi also authorize the method, though neither has announced efforts to implement it. Alabama declined to disclose any details of its plans, or how it was able to obtain the materials for the new method.

In Nevada, a legislative effort to repeal the state’s death penalty passed the State Assembly but, despite strong support in the chamber, did not receive a committee hearing or a vote in the State Senate. Repeal proponents questioned the role of Senate Majority Leader Nicole Cannizzaro and Senate Judiciary Committee Chair Melanie Scheible — both of whom work as prosecutors in the Clark County District Attorney’s office — in blocking Senate consideration of the bill. Their boss, Clark County District Attorney Scott Wolfson, was the lead witness against the bill in the House Judiciary Committee. Following House passage of the measure, he announced his intention to seek an execution date for Zane Floyd, but claimed the timing was coincidental.

On June 10, the Nevada Department of Corrections (NVDOC) indicated that it intended to execute Floyd with a three- or four-drug combination that has never been used before to put a prisoner to death. NVDOC said its execution cocktail would be drawn from six possible drugs, including fentanyl and ketamine. Hikma Phamaceuticals, a maker of ketamine, then sent a cease-and-desist letter to Nevada Attorney General Aaron Ford threatening to sue the state for illegally obtaining its drug. Shortly afterwards, a federal district court stayed Floyd’s execution for three months saying the state’s late disclosure of its protocol did not provide sufficient time to determine the constitutionality of the untested drug combination.

The 2021 protocol was not the first time Nevada had attempted to employ an untested drug combination to execute a prisoner. In 2017, the state adopted an untried three-drug protocol of diazepam, fentanyl, and cisatracurium to execute Scott Dozier. A state court judge halted Dozier’s execution, issuing an injunction based on its finding that NVDOC had obtained drugs produced by Alvogen, Inc. “by subterfuge” and prohibiting the state from using Alvogen’s drugs.

Idaho’s unsuccessful attempt to execute Gerald Pizzuto, Jr. also highlighted the questionable lengths to which state prosecutors have gone to put prisoners to death. Prosecutors obtained a death warrant to execute Pizzuto on June 2, despite knowing he has been in hospice care confined to a wheelchair for more than a year, suffering from late-stage bladder cancer, chronic heart and coronary artery disease, coronary obstructive pulmonary disease, and Type 2 diabetes with related nerve damage to his legs and feet. Pizzuto has had two heart attacks and has had four stents implanted around his heart. A state trial judge stayed Pizzuto’s execution to permit the state pardons board to review his petition for clemency.

Pizzuto’s death sentence is also tainted by prosecutorial and judicial misconduct. Evidence that was withheld from the defense at the time of trial revealed that his prosecutor, his trial judge, and the co-defendant’s counsel met secretly to broker a deal in which the co-defendant would testify against Pizzuto in exchange for a lenient sentence. The prosecution then deliberately elicited false testimony from the co-defendant — which the judge knew to be perjurious — that he expected to be sentenced to life in prison for his role in the murder.

At the federal level, the Biden administration frustrated death-penalty opponents by failing to set any policy on whether the administration would pursue new capital prosecutions, defend death sentences that already had been imposed, or commute existing federal death sentences to prevent a future president from carrying out additional executions. In apparent contradiction of Biden’s campaign pledge to work to end the death penalty, the Department of Justice filed a brief in the U.S. Supreme Court seeking reinstatement of the death penalty against Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, whose death sentence in the Boston Marathon bombing had been overturned by a federal appeals court.

The White House press office said the action did not constitute a retreat from the President’s campaign pledge, saying the Justice Department had “independence regarding such decisions.” In an email to reporters on June 15, Deputy White House Press Secretary Andrew Bates wrote, “President Biden has made clear that he has deep concerns about whether capital punishment is consistent with the values that are fundamental to our sense of justice and fairness. … The President believes the Department should return to its prior practice, and not carry out executions.”

One week later, U.S. Attorney General Merrick Garland said he is reviewing the Department’s policies on the federal death penalty and would issue a policy statement “soon.”