DPIC Analysis: Use or Threat of Death Penalty Implicated in 19 Exoneration Cases in 2019

Misconduct was present in 95% of the cases.

The exonerees lost nearly 500 years to wrongful incarceration.

- Introduction

- The Factors that Contributed to These Wrongful Convictions

- Official Misconduct

- Perjury/False Accusation

- False or Fabricated Confessions

- Mistaken Witness Identification

- Appendix A. Official Misconduct Data

- Appendix B. Data Regarding Perjury/False Accusation

Introduction Top

The use or threat of the death penalty was a factor in more than 13% of exonerations across the United States in 2019 and nearly 95% of those cases involved some form of major misconduct, a Death Penalty Information Center analysis of data from the National Registry of Exonerations has revealed. The DPIC review found that the death penalty played a role in at least 19 of the 143 exonerations in 2019 (13.3%) listed in the Registry’s annual exonerations report, resulting in nearly 500 years lost to wrongful incarceration. Based on the National Registry’s designation of factors contributing to the wrongful convictions, Official Misconduct and/or Perjury or False Accusation was present in all but one of the wrongful incarcerations in which the death penalty was implicated (18 of 19, or 94.7%).

The prevalence of misconduct was even greater in these cases than the already high historical rate at which misconduct occurs in exonerations. A September 2020 report by the National Registry of Exonerations, Government Misconduct and Convicting the Innocent found that misconduct was present in more than half of all exonerations since 1989, rising to nearly three-quarters of the cases in which exonerees had been wrongfully convicted and sentenced to death.

“The numbers show that the death penalty has dangerous effects on the criminal justice system that go far beyond the already significant risk of executing innocent people,” said DPIC Executive Director Robert Dunham. “Innocent people confess to crimes they didn’t commit to avoid the possibility of being executed. Suspects, both innocent and guilty, who are threatened with the death penalty if they do not cooperate with law enforcement provide false testimony that sends innocent people to jail, often for decades. The data suggest that the misuse of the death penalty as a coercive interrogation and plea bargaining tool poses a far greater threat to the fair administration of the criminal laws than we had previously imagined.”

The 2019 Annual Report of the National Registry of Exonerations identifies three former death-row prisoners who were exonerated in 2019: Clifford Williams, Jr.; Charles Ray Finch; and Christopher Williams. Collectively, they spent 111 years wrongfully incarcerated for murders they did not commit. However, DPIC’s review of the National Registry’s data identified at least sixteen other exonerees not sentenced to death who either were wrongfully convicted after they or others associated with the case were threatened with the death penalty or had their wrongful incarcerations extended because witnesses had been threatened with the death penalty if they testified for the defense.

In addition to the three death-row exonerations:

- Prosecutors sought the death penalty against four other men.[1] In three of the cases, jurors convicted them of lesser degrees of murder or rejected circumstances that would have made them eligible for the death penalty. In the fourth case, prosecutors withdrew the death penalty at the start of trial.

- An 18-year-old was not capitally charged because of his age but was tried before a death-qualified jury because his co-defendant (who also was exonerated in 2019) was capitally tried.[2]

- Nine falsely confessed as a result of the death penalty.[3] Six gave false confessions after law enforcement threatened them with the death penalty. One of them pled guilty to rape and murder to avoid the death penalty; the actual killer remained free and committed another rape and murder. Three falsely confessed to rape to avoid capital murder charges and then falsely implicated a fourth man (also exonerated in 2019) in the murder. A 16-year-old falsely confessed under pressure from his older brother so the brother would not face the death penalty, and then a prosecution witness who had been threatened with the death penalty falsely implicated the teen.

- Three were convicted of murder after prosecutors presented false testimony from witnesses who had been threatened with the death penalty.[4]

- One had his exoneration obstructed when prosecutors threatened a post-conviction witness with the death penalty for admitting to the murder and then charged the witness with perjury for his truthful admission.[5]

[1] Keith West, Samuel Bonner, Willie Veasy, Robert Yell.

[3] Dean McKee, Stanley Mozee, Ronald Stewart, Christopher Tapp, Veasy, Demond Weston (murder); James Long, James Pitts, Jr., and Michael Shelton (rape).

[4] Dennis Allen, Richard Kussmaul, and McKee.

Nationwide, the 143 men and women exonerated in 2019 spent a total of 1,908 years in prison, a record for any year. The 19 men whose cases involved the wrongful use or threat of the death penalty accounted for one quarter of that total, losing 480 years to wrongful incarceration. On average, the 2019 exonerees spent 13.3 years each wrongfully incarcerated. The average wrongful imprisonment of exonerees in cases involving death-penalty-related abuses was nearly double that figure, at 25.3 years — an average of more than a quarter century per person.

More than half (76) of the 143 men and women exonerated across the United States in 2019 had been wrongfully convicted of homicide. All of the 19 cases DPIC identified as involving the wrongful pursuit or threatened use of the death penalty were murder cases, though not all of the exonerees were ultimately charged with or convicted of murder. Fifteen of the exonerees were convicted of some degree of murder; but one was convicted of manslaughter and three others pled guilty to rape in a rape/murder case.

The Factors that Contributed to These Wrongful Convictions Top

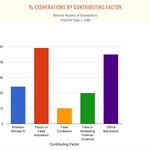

Historically, official misconduct and perjury or false accusation have been the leading factors contributing to the wrongful conviction of innocent men and women in the United States. As of April 9, 2020, the National Registry of Exonerations reported that Perjury or False Accusation contributed to 58.5% of the 2,588 exonerations it has identified. Official Misconduct was a factor in 53.8% of the exoneration cases. No other factor came close as a contributing cause to wrongful convictions.

The National Registry’s report on government misconduct, which reviewed 2,400 of those exonerations, found misconduct in 54% of all exonerations since 1989, and that misconduct tended to rise as the charges involved became more serious. Misconduct was present in 72% of the cases in which exonerees had been sentenced to death.

The Registry also found that government misconduct was more likely to occur in cases involving Black defendants. Overall, 57% of Black exonerees and 52% of white exonerees had been victims of police or prosecutorial misconduct, but, the report found, “this gap is much larger among exonerations for murder (78% to 64%) — especially those with death sentences (87% to 68%).” In the 2019 exoneration cases in which police or prosecutors sought or threatened to use the death penalty, DPIC found white exonerees were victims of misconduct 75% of the time (6 of 8 cases), while all eleven Black exonerees had been victims of misconduct.

Research has shown that there is a direct relationship between the seriousness of a crime and the likelihood of a miscarriages of justice. As University of Denver professors Scott Phillips and Jamie Richardson describe it in their law review article, The Worst of the Worst: Heinous Crimes and Erroneous Evidence: “the ‘worst of the worst crimes,’ produce the ‘worst of the worst evidence.’”

Phillips’ and Richardson’s review of more than 1,500 cases in which convicted prisoners were later exonerated found that “as the seriousness of a crime increases, so too does the chance of a wrongful conviction.” They explain that prosecutions for the most serious crimes tend to involve the most inaccurate and unreliable evidence, and the risks are greatest in cases producing murder convictions and death sentences. “The types of vile crimes in which the state is most apt to seek the death penalty are the same crimes in which the state is most apt to participate in the production of erroneous evidence …, from false confession to untruthful snitches, government misconduct, and bad science.”

DPIC’s analysis of the National Registry of Exonerations data suggests that this was again the case in 2019. Official Misconduct or Perjury or False Accusation were present in 94.7% of the 2019 exonerations in which prosecutors pursued the death penalty or police or prosecutors threatened defendants or witnesses with the death penalty if they did not confess and/or provide testimony against murder defendants or refrain from providing testimony that could exonerate a prisoner wrongfully convicted of murder. In 78.9% of the exonerations in which the death penalty was implicated, both factors were present.

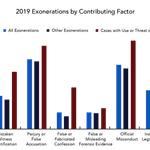

Perjury or False Accusation and Official Misconduct were bad in the exoneration cases in general in 2019 and were worse in murder cases than in the non-homicide exonerations. But as bad as these forms of misconduct were in murder cases as a whole, they were even worse in the exoneration cases that were capitally prosecuted or in which defendants and/or witnesses were threatened with the death penalty.

From the Executive Summary to the 2019 National Registry of Exonerations Annual Report

Overall, Perjury or False Accusation (P/FA) was present in 101 of the 143 exonerations (70.6%) in 2019, making it the most prevalent factor in the year’s exonerations. P/FA was more pronounced in homicide cases, where it was present 76.3% of the time (58 of 76 cases), as compared with 43 of 67 (64.2%) non-homicide cases. That figure rose again to 84.2% in cases in which the death penalty was pursued or its use was threatened (16 of 19 exonerations).

Official Misconduct by police, prosecutors, or other government actors — most commonly in the form of withholding exculpatory evidence — was the second most frequent contributing factor to exonerations in 2019, occurring in nearly two-thirds of all exonerations (93 of 143, or 65.0%). As anticipated, Official Misconduct was even more prevalent in wrongful homicide convictions, where it was present three-quarters of the time (57 of 76 cases, 75.0%). But the rate of Official Misconduct soared when prosecutors pursued capital prosecutions or police or prosecutors threatened suspects or witnesses with the death penalty. Official Misconduct was the single most frequent contributing factor in those cases, where it was present in 89.5% of the exonerations (17 of 19).

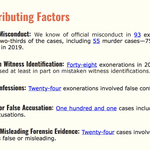

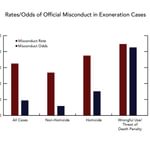

To understand the increased risk of Official Misconduct and Perjury/False Accusation in the death-penalty-related cases, we calculated both the probability and the odds that these factors would be present in an exoneration for four classes of cases: (1) all of the 2019 exonerations; 2019 exonerations in non-homicide convictions — that is, cases in which the exoneree had been wrongfully convicted of a crime or crimes other than murder or manslaughter; 2019 homicide exonerations; and 2019 exonerations implicating the death penalty — that is, cases in which an accused had been capitally tried or non-capital tried cases in which police or prosecutors had threatened the exoneree or a witness with the death penalty. What we found was dramatic.

Official Misconduct Top

- The odds that Official Misconduct contributed to a wrongful conviction was 4.57 times greater when the death penalty was pursued or its use was threatened, as compared to the 2019 exonerations as a whole.

- The odds that Official Misconduct would be a factor increased more than seven-fold (7.32 times greater) in the death-penalty-related cases, as compared to the non-homicide exonerations.

- As compared to homicide exonerations as a whole, Official Misconduct was nearly twenty percent more likely (19.3%) when a case involved wrongful use or threat of the death penalty, and the odds that Official Misconduct would be present as a factor were 2.83 times greater than for homicide exonerations as a whole.

Perjury/False Accusation Top

- The odds that Perjury or False Accusation contributed to a wrongful conviction more than doubled (2.2 times higher) when the death penalty was pursued or its use was threatened.

- The odds that P/FA would be a factor were nearly triple (2.98 times higher) than for non-homicide exonerations.

- As compared to homicide exonerations as a whole, Perjury or False Accusation was ten percent more likely when a case involved wrongful use or threat of the death penalty and the odds that P/FA would be present as a factor were 1.67 times higher than for homicide exonerations as a whole.

Although every type of error or misconduct was more likely to be present in exonerations involving the use or threat of the death penalty than in other exonerations, the two areas in which the differences were greatest were wrongful convictions in which prosecutors presented false or fabricated confessions or mistaken eyewitness identifications.

False or Fabricated Confessions Top

Twenty-four of the 143 exonerations reported by the National Registry in 2019 involved False or Fabricated Confessions (16.8%). One-third of the false confession exonerations were cases in which an accused had been threatened with the death penalty (8 of 19 cases). False confessions were 3.26 times more likely to occur in a case in which prosecutors threatened to pursue the death penalty or police threatened suspects or witnesses with the death penalty (42.1%) than in other exoneration cases (12.9%). And if one were attempting to predict an exoneration case in which a false or fabricated confession contributed to the wrongful conviction, the odds that one would find it in a case in involving the use or threat of the death penalty were nearly five times greater (4.91) than in the other cases.

Mistaken Witness Identification Top

About one third of the National Registry’s 2019 exonerations involved Mistaken Eyewitness Identifications (48 of 143 cases, or 33.6%). However, misidentifications were a factor in more than half of the cases in which prosecutors pursued or law enforcement threatened the use of the death penalty (11 of 19 cases, or 57.9%) and were nearly twice as likely to occur (1.94) in the death penalty cases than in other exoneration cases (37 of 124 cases, 29.8%). Altogether, the odds that mistaken eyewitness identification would contribute to a wrongful conviction in the 2019 exoneration cases was nearly three-and-a-quarter times greater (3.23) in wrongful conviction cases involving the use or threat of the death penalty than in other cases.

Exonerations by Contributing Factor |

|||||||||||

All 2019 Exoneration Cases |

|||||||||||

Mistaken Witness Identification |

Perjury/False Accusation |

False or Fabricated Confession |

False or Misleading Forensic Evidence |

Official Misconduct |

Inadequate Legal Defense |

||||||

No. |

% |

No. |

% |

No. |

% |

No. |

% |

No. |

% |

No. |

% |

48 |

33.6 |

101 |

70.6 |

24 |

16.8 |

24 |

16.8 |

93 |

65.0 |

56 |

39.2 |

2019 Exoneration Cases Involving Use or Threat of Death Penalty |

|||||||||||

|

Mistaken Witness Identification |

Perjury/False Accusation |

False or Fabricated Confession |

False or Misleading Forensic Evidence |

Official Misconduct |

Inadequate Legal Defense |

||||||

No. |

% |

No. |

% |

No. |

% |

No. |

% |

No. |

% |

No. |

% |

11 |

57.9 |

16 |

84.2 |

8 |

42.1 |

4 |

21.1 |

17 |

89.5 |

7 |

36.8 |

All Other 2019 Exoneration Cases |

|||||||||||

|

Mistaken Witness Identification |

Perjury/False Accusation |

False or Fabricated Confession |

False or Misleading Forensic Evidence |

Official Misconduct |

Inadequate Legal Defense |

||||||

No. |

% |

No. |

% |

No. |

% |

No. |

% |

No. |

% |

No. |

% |

37 |

29.8 |

85 |

68.5 |

16 |

12.9 |

20 |

16.1 |

76 |

61.3 |

49 |

39.5 |

Last Name |

First Name |

Age |

Race |

State |

County |

Crime |

Sentence |

Year Con-victed |

Years in Jail |

DNA |

MWID |

FC |

P/FA |

F/MFE |

OM |

ILD |

How Death Penalty Implicated |

Dennis |

36 |

B |

TX |

Dallas |

Murder |

Life |

2000 |

14 |

DNA* |

MWID |

P/FA |

OM |

Convicted based on false testimony by a witness who had been threatened with the death penalty. |

||||

Samuel |

20 |

B |

CA |

Los Angeles |

Murder |

Life without parole |

1983 |

36 |

P/FA |

OM |

Capitally prosecuted. Prosecutors dropped the death penalty before the penalty phase after the jury found that Bonner was not the shooter. |

||||||

Charles |

38 |

B |

NC |

Wilson |

Murder |

Death |

1976 |

43 |

MWID |

P/FA |

F/MFE |

OM |

ILD |

Capitally prosecuted and sentenced to death. |

|||

Richard |

21 |

W |

TX |

McLennan |

Murder |

Life without parole |

1994 |

25 |

DNA* |

MWID |

P/FA |

F/MFE |

OM |

ILD |

Convicted based upon the testimony of three men who falsely confessed to rape after being threatened with death penalty and falsely implicated Kussmaul. See James Pitts Jr., James Long, and Michael Shelton. |

||

Dean |

16 |

W |

FL |

Hillsborough |

Murder |

Life |

1988 |

29 |

DNA* |

FC |

P/FA |

OM |

His older brother got him to falsely confess because he was 16 and would not get the death penalty; a prosecution witness then falsely implicated him after being threatened with the death penalty. |

||||

John |

21 |

B |

PA |

Philadelphia |

Murder |

Life without parole |

1998 |

20 |

P/FA |

OM |

Prosecutors threatened a post-conviction witness with the death penalty for admitting to the murder and then charged the witness with perjury after he provided exculpatory testimony. |

||||||

Stanley |

39 |

B |

TX |

Dallas |

Murder |

Life |

2000 |

14 |

DNA* |

FC |

P/FA |

OM |

Falsely confessed after having been threatened with the death penalty |

||||

Hubert |

18 |

B |

FL |

Duval |

Murder |

Life |

1976 |

42 |

MWID |

OM |

ILD |

Non-capitally prosecuted. Jointly tried before a death-qualified jury with his uncle, co-defendant Clifford Williams, who was sentenced to death. |

|||||

Ronald |

23 |

W |

FL |

Broward |

Murder |

50 years |

1985 |

23 |

DNA* |

MWID |

P/FA |

Falsely confessed and pled guilty to 2nd degree murder to avoid the death penalty. |

|||||

Christopher |

20 |

W |

ID |

Bonneville |

Murder |

Life |

1998 |

21 |

DNA |

FC |

P/FA |

OM |

ILD |

Falsely confessed after being threatened with the death penalty. |

|||

Willie |

26 |

B |

PA |

Philadelphia |

Murder |

Life without parole |

1993 |

26 |

MWID |

FC |

P/FA |

OM |

Falsely confessed after being threatened with the death penalty. Capitally prosecuted after contesting his confession but was convicted of lesser degree of murder. |

||||

Keith |

19 |

B |

KY |

Jefferson |

Murder |

Life |

1995 |

24 |

P/FA |

OM |

ILD |

Capitally prosecuted but convicted of lesser degree of murder. |

|||||

Demond |

17 |

B |

IL |

Cook |

Murder |

75 years |

1992 |

27 |

MWID |

FC |

P/FA |

OM |

Falsely confessed after being beaten by officers under the command of Lt. Jon Burge and threatened with the death penalty. |

||||

Christopher |

29 |

B |

PA |

Philadelphia |

Murder |

Death |

1993 |

26 |

P/FA |

F/MFE |

OM |

ILD |

Capitally prosecuted and sentenced to death. |

||||

Clifford |

33 |

B |

FL |

Duval |

Murder |

Death |

1976 |

42 |

MWID |

OM |

ILD |

Capitally prosecuted and sentenced to death. |

|||||

Robert |

27 |

W |

KY |

Logan |

Man-slaughter |

52 years |

2006 |

11 |

F/MFE |

Charged with arson and capital murder based on junk science. Prosecution withdrew the death penalty at the start of the trial. |

|||||||

Pitts, Jr. |

James |

20 |

W |

TX |

McLennan |

Sexual Assault |

20 years |

1994 |

20 |

DNA* |

MWID |

FC |

P/FA |

OM |

Falsely confessed after being threatened with death penalty. |

||

James |

21 |

W |

TX |

McLennan |

Sexual Assault |

20 years |

1994 |

20 |

DNA* |

MWID |

FC |

P/FA |

OM |

Falsely confessed after being threatened with death penalty. |

|||

Michael |

22 |

W |

TX |

McLennan |

Sexual Assault |

20 years |

1994 |

17 |

DNA* |

MWID |

FC |

P/FA |

OM |

Falsely confessed after being threatened with death penalty. |

The report spotlighted several 2019 exonerations linked to the misuse of the death penalty. Clifford Williams, Jr. was sentenced to death in Florida in 1976 and spent 42 years in prison before the Duval County Conviction Integrity Unit reinvestigated his case and found “no credible evidence of guilt and … credible evidence of innocence.” No physical evidence linked Williams to the crime, and witness accounts contradicted the ballistics evidence in the case. Williams’ defense counsel had presented no witnesses, ignoring 40 alibi witnesses who could have testified that Williams was at a birthday party at the time of the crime. Like the vast majority of Florida death-row exonerees, Williams’ jury had not voted unanimously for death; in fact, his trial judge overrode a jury recommendation of a life sentence.

Charles Ray Finch also was sentenced to death in 1976. Finch’s case involved both leading causes of wrongful convictions: official misconduct and perjury. Police in Wilson County, North Carolina obtained witness identification of Finch through suggestive lineups and the prosecution presented false testimony linking Finch to a weapon that did not actually match the one used in the murder. Several prosecution witnesses later testified that they had been pressured into giving false testimony.

The year’s third death-row exoneration, that of Christopher Williams in Pennsylvania, was the result of official misconduct and false accusation by a self-interested informant. Philadelphia prosecutors deliberately withheld exculpatory evidence. The key prosecution witness cooperated with prosecutors in exchange for avoiding capital prosecution for six different murders. Williams’ case was one of thirteen homicide exonerations in Philadelphia in 2019, and one of nine aided by investigations by the DA’s Conviction Integrity Unit.

Other cases referenced in the report involved the use or threat of the death penalty:

- Robert Yell was exonerated in Kentucky of the arson-related murder of his son. In mid-March 2020, he filed a civil rights lawsuit alleging that law enforcement framed him. Prosecutors initially sought the death penalty in the case but withdrew it at the start of Yell’s trial. He was convicted of manslaughter and sentenced to 52 years, but his attorneys say the evidence against him was fabricated and that law enforcement hid evidence that the fire was caused by a faulty electrical outlet.

- Christopher Tapp was exonerated in Idaho after a recording came to light that revealed police had told Tapp he faced the death penalty if he didn’t confess, lied to him that he had failed polygraph tests, suggested he had repressed memories of the killing, and offered him leniency — including possible immunity — for implicating others.

- Florida exoneree Ronald Stewart was posthumously cleared of the murder of Regina Harrison, which he had confessed to under threat of a death sentence. His case was re-examined after Jack Jones, who was executed in Arkansas in 2017, sent a letter to his sister confessing to Harrison’s murder. After Florida police deemed Harrison’s case closed, Jones went on to commit an additional rape and murder.

— Robert Dunham, Executive Director

October 23, 2020

Appendix A. Official Misconduct Data Top

The Prevalence of Official Misconduct By Type of Exoneration Case |

||||

Category of Case |

Number of Cases |

# Involving Misconduct |

% Involving Misconduct |

Odds of Official Misconduct |

All Cases |

143 |

93 |

65.0350 |

1.86:1 |

Non-Homicide |

67 |

36 |

53.7313 |

1.16129:1 |

Homicide |

76 |

57 |

75.0000 |

3:1 |

Wrongful Use/Threat of Death Penalty |

19 |

17 |

89.4737 |

8.5:1 |

Comparative Rates of Official Misconduct By Type of Exoneration Case |

|||||

Category of Case |

Misconduct Rate (%) |

Misconduct Rate in Comparison to: |

|||

All Cases |

Non-Homicide |

Homicide |

Wrongful Use/Threat of DP |

||

All Cases |

65.0350 |

X |

1.21 times higher |

1.15 times lower |

1.38 times lower |

Non-Homicide |

53.7313 |

1.21 times lower |

X |

1.40 times lower |

1.67 times lower |

Homicide |

75.0000 |

1.15 times higher |

1.40 times higher |

X |

1.19 times lower |

Wrongful Use/Threat of Death Penalty |

89.4737 |

1.38 times higher |

1.67 times higher |

1.19 times higher |

X |

The Odds of Official Misconduct By Type of Exoneration Case |

|||||

Category of Case |

Odds of Misconduct |

Misconduct Odds in Comparison to: |

|||

All Cases |

Non-Homicide |

Homicide |

Wrongful Use/Threat of DP |

||

All Cases |

1.86:1 |

X |

1.60 times higher |

1.61 times lower |

4.57 times lower |

Non-Homicide |

1.16:1 |

1.60 times lower |

X |

2.58 times lower |

7.32 times lower |

Homicide |

3:1 |

1.61 times higher |

2.58 times higher |

X |

2.83 times lower |

Wrongful Use/Threat of Death Penalty |

8.5:1 |

4.57 times higher |

7.32 times higher |

2.83 times higher |

X |

Appendix B. Data Regarding Perjury/False Accusation Top

The Prevalence of Perjury/False Accusation By Type of Exoneration Case |

||||

Category of Case |

Number of Cases |

# Involving Perjury/False Accusation |

% Involving Perjury/False Accusation |

Odds of Perjury/False Accusation |

All Cases |

143 |

101 |

70.6294 |

2.40476:1 |

Non-Homicide |

67 |

43 |

64.1791 |

1.79167:1 |

Homicide |

76 |

58 |

76.3158 |

3.22222:1 |

Wrongful Use/Threat of Death Penalty |

19 |

16 |

84.2105 |

5.33333:1 |

Comparative Rates of Perjury/False Accusation By Type of Exoneration Case |

|||||

Category of Case |

Perjury/ False Accusation Rate (%) |

Perjury/False Accusation Rate in Comparison to: |

|||

All Cases |

Non-Homicide |

Homicide |

Wrongful Use/Threat of DP |

||

All Cases |

70.6294 |

X |

1.10 times higher |

1.08 times lower |

1.19 times lower |

Non-Homicide |

64.1791 |

1.10 times lower |

X |

1.19 times lower |

1.31 times lower |

Homicide |

76.3158 |

1.08 times higher |

1.19 times higher |

X |

1.10 times lower |

Wrongful Use/Threat of Death Penalty |

84.2105 |

1.19 times higher |

1.31 times higher |

1.10 times higher |

X |

Comparative Odds of Perjury/False Accusation By Type of Exoneration Case |

|||||

Category of Case |

Odds of Perjury/ False Accusation |

Perjury/False Accusation Odds in Comparison to: |

|||

All Cases |

Non-Homicide |

Homicide |

Wrongful Use/Threat of DP |

||

All Cases |

2.40476:1 |

X |

1.34 times higher |

1.34 times lower |

2.22 times lower |

Non-Homicide |

1.79167:1 |

1.34 times lower |

X |

1.80 times lower |

2.98 times lower |

Homicide |

3.22222:1 |

1.34 times higher |

1.80 times higher |

X |

1.66 times lower |

Wrongful Use/Threat of Death Penalty |

5.33333:1 |

2.22 times higher |

2.98 times higher |

1.66 times higher |

X |