The Death Penalty in 2021: Year End Report

Virginia’s Historic Abolition Highlights Continuing Decline of Death Penalty

Executions characterized by botches and outlier practices

Posted on Dec 16, 2021

- Introduction

- Death Penalty Developments in the States and Counties

- Federal Death Penalty

- Execution and Sentencing Trends

- Innocence and Clemency

- Problematic Executions

- A Deadly Year for Prisoners with Intellectual Disability

- New Sentences Continue to Highlight Systemic Death Penalty Flaws

- Public Opinion

- Supreme Court

- Key Quotes

- Downloadable Resources

Key Findings

- Virginia becomes 23rd state, and first in the South, to abolish the death penalty

- Seventh consecutive year with fewer than 30 executions and 50 new death sentences

- New study finds one exoneration for every 8.3 executions

- Federal execution spree ends, new administration halts all federal executions and announces policy review

Introduction Top

The death penalty in 2021 was defined by two competing forces: the continuing long-term erosion of capital punishment across most of the country, and extreme conduct by a dwindling number of outlier jurisdictions to continue to pursue death sentences and executions.

Virginia’s path to abolition of the death penalty was emblematic of capital punishment’s receding reach in the United States. A combination of changing state demographics, eroding public support, high-quality defense representation, and the election of reform prosecutors in many key counties produced a decade with no new death sentences in the Commonwealth. As the state grappled with its history of slavery, Jim Crow, lynchings, and the 70th anniversary of seven wrongful executions, the governor and legislative leaders came to see the end of the death penalty as a crucial step towards racial justice. On March 24, Virginia became the first southern state to repeal capital punishment, and expanded the death-penalty-free zone on the U.S. Atlantic coast from the Canadian border of Maine to the northern border of the Carolinas.

Death Row Population By State†

| State | 2021 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|

| California | 699 | 724 |

| Florida | 338 | 346 |

| Texas | 198 | 214 |

| Alabama | 171 | 172 |

| North Carolina | 139 | 145 |

| Ohio | 136 | 141 |

| Pennsylvania | 130 | 142 |

| Arizona | 118 | 119 |

| Nevada | 66 | 71 |

| Louisiana | 65 | 69 |

| Tennessee | 49 | 51 |

| U.S. Government | 46 | 62 |

| Georgia | 45 | 45 |

| Oklahoma | 43 | 47 |

| Mississippi | 40 | 44 |

| South Carolina | 39 | 39 |

| Arkansas | 31 | 31 |

| Kentucky | 27 | 28 |

| Oregon | 24 | 27 |

| Missouri | 21 | 22 |

| Nebraska | 12 | 12 |

| Kansas | 9 | 10 |

| Idaho | 8 | 8 |

| Indiana | 8 | 8 |

| Utah | 7 | 7 |

| U.S. Military | 4 | 4 |

| Montana | 2 | 2 |

| New Hampshire^^ | 1 | 1 |

| South Dakota | 1 | 1 |

| Wyoming | 1 | 1 |

| Virginia^ | 2 | |

| Total | 2474‡ | 2591‡ |

† Data from NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund for July 1 of the year shown

^ Virginia abolished the death penalty with an effective date of July 1, 2021. The bill reduced the state’s two death sentences to life without parole.

^^ New Hampshire prospectively abolished the death penalty May 30, 2019.

‡ Persons with death sentences in multiple states

are only included once in the total

In the West, where an execution-free zone spans the Pacific coast from Alaska to Mexico, the Oregon Supreme Court began removing prisoners from the state’s death row based on a 2019 law that redefined the crimes that constitute capital murder. Nationwide, mounting distrust of the death-penalty system was reflected in public opinion polling that measured support for capital punishment at near half-century lows. With Virginia’s abolition, a majority of states have now abolished the death penalty (23) or have a formal moratorium on its use (3). An additional ten states have not carried out an execution in at least ten years.

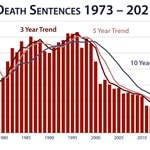

2021 saw historic lows in executions and near historic lows in new death sentences. As this report goes to press, eighteen people were sentenced to death, tying 2020’s number for the fewest in the modern era of the death penalty, dating back to the Supreme Court ruling in Furman v. Georgia that struck down all existing U.S. death-penalty statutes in 1972. The eleven executions carried out during the year were the fewest since 1988. The numbers were unquestionably affected by the pandemic but marked the seventh consecutive year of fewer than 50 death sentences and 30 executions. Both measures pointed to a death penalty that was geographically isolated, with just three states — Alabama, Oklahoma, and Texas — accounting for a majority of both death sentences and executions.

The few jurisdictions that scheduled or carried out executions and imposed new death sentences pursued the death penalty with apparent disregard for due process, judicial review of execution methods, or potentially meritorious claims of intellectual disability, incompetence to be executed, and innocence. Oklahoma botched the execution of John Grant and then denied the execution had been problematic. Arizona authorized executions with the same lethal gas the Nazis had used to murder more than a million people in their World War II death camps. South Carolina moved to adopt the electric chair as its default execution method, with the firing squad as a “humane” alternative.

The federal government’s historically aberrant spree of thirteen executions in six months concluded with three executions carried out less than ten days before the inauguration of a president who had expressed his opposition to capital punishment. The six transition-period executions were the most ever in American history. Those executed in 2021 included a severely mentally ill woman who never received a hearing on her competency to be executed, an intellectually disabled man who never received review of his claim that he was ineligible for the death penalty, and a man who without dispute did not kill anybody. Two of the men who were executed were among the more than two dozen death-row prisoners who contracted COVID-19 as a result of prior federal superspreader executions.

The federal execution spree also raised questions about the legitimacy of the U.S. Supreme Court as a neutral arbiter of the law, as the Court actively intervened to lift lower court stays or injunctions issued by conservative and liberal judges alike, denying judicial review of serious and unresolved legal and constitutional issues. The Biden administration set no policy on the federal death penalty, allowing the Department of Justice to make decisions on capital prosecutions and appeals on a case-by-case basis. Attorney General Merrick Garland issued a memorandum saying no new executions would be authorized while DOJ reviewed changes in death-penalty policy put in place during the Trump administration. He made no commitments on the pursuit of new federal death sentences or the possibility of federal executions after the review.

Executions and death sentences in 2021 continued to highlight the arbitrary and discriminatory application of the death penalty. Rather than representing the “worst of the worst” offenders, all but one of the eleven people executed in 2021 had one or more significant impairments, including: evidence of mental illness; brain injury, developmental brain damage, or an IQ in the intellectually disabled range; or chronic serious childhood trauma, neglect, and/or abuse. Their cases were tainted by racial bias, inadequate representation, and disproportionate sentencing. The year’s new death sentences were also badly flawed, with more than a quarter (27.8%) imposed either by non-unanimous juries or by judges after defendants waived jury sentencing or in states that denied defendants the right to a sentencing jury.

Sentences and executions disproportionately involved victims who were white and female. Once again, only defendants of color were executed for cross-racial murders and no white defendant was sentenced to death in a trial that did not involve at least one white victim. Three high-profile cases — each involving likely innocent Black men sentenced to death for killing white victims — symbolized the enduring racial injustice of the nation’s death penalty. Julius Jones and Pervis Payne were spared execution, only to be resentenced to life in prison. A Texas trial judge in a county with a history of lynchings heard extensive evidence of Rodney Reed’s innocence, then credited the testimony of a disgraced white police officer who was the likely killer over that of nearly a dozen other witnesses to recommend that Reed be denied a new trial.

Two more innocent death-row prisoners were exonerated in 2021, and a DPIC review of the more than 9,600 death sentences imposed in the U.S. since 1972 discovered another eleven previously unrecorded death-row exonerations. That raised the number of death-row exonerations to 186 — one for every 8.3 executions in the modern era.

As death-penalty usage continues to erode, its flaws become even more evident. As the few jurisdictions that seek to pursue it engage in shocking conduct that undermines or evades judicial review, the cases resulting in death sentences and executions increasingly reflect arbitrariness, discrimination, and systemic failures that represent the worst of the worst judicial process. These very flaws, brought into stark relief as the death penalty becomes more rare, are causing more prosecutors, jurors, and voters in much of the country to decide to abandon capital punishment altogether, concentrating its continuing practice in a dwindling number of outlier jurisdictions with an historical legacy of slavery, lynching, and Jim Crow and a modern history of abusive law enforcement.

Death Penalty Developments in the States and Counties Top

Key Findings

- Virginia abolishes death penalty; 23rd state, first southern state to do so

- Oregon Supreme Court ruling continues erosion of death penalty in the West; decision is expected to clear death row

- Bipartisan abolition efforts proceed in Ohio and Utah

Death-penalty developments in the states in 2021 reflected the continuing long-term erosion of capital punishment in much of the country, with pushback from a small number of outlier jurisdictions who turned to brutal and unpopular execution methods or distorted the legal process in their fervor to resume or continue executions.

From Alaska southward to New Mexico’s borders with Texas and Mexico, there were no executions in 2021 and only two Southern California counties imposed any death sentences. From the Pacific Northwest to the Atlantic Ocean, across the entire northern border with Canada, and from the northern tip of Maine south to the Florida Keys, there were no executions and just two death sentences imposed in Florida. The practical disappearance of the death penalty in these states was accompanied by an expanding zone of official death penalty abolition, spanning the U.S. Atlantic coast from Maine to the northern border of the Carolinas. There were no executions west of Texas for a seventh straight year, where the combination of death-penalty abolition and gubernatorial moratoria on executions formally bars executions the full length of the U.S. Pacific coast.

Governor Ralph Northam signs the bill abolishing Virginia’s death penalty

Virginia’s historic abolition of the death penalty on March 24, 2021, highlighted the U.S.’s death-penalty erosion. The commonwealth — which from colonial times had carried out more executions than any other U.S. jurisdiction — became the first southern state to end capital punishment. Governor Ralph Northam, who endorsed abolition in his State of the Commonwealth address prior to the opening of the 2021 legislative session, said at the bill signing, “[t]here is no place today for the death penalty in this commonwealth, in the South, or in this nation.” The repeal effort emphasized the historical links between slavery, Jim Crow, lynchings, and the death penalty. Delegate Mike Mullin, the House sponsor of the bill, said, “We’ve carried out the death penalty in extraordinarily unfair fashion. Only four times out of nearly 1400 [executions] was the defendant white and the victim Black.” That history underlined the symbolic importance of the death penalty being abolished in the former capital of the Confederacy.

Further underscoring the relationship between death-penalty repeal and racial healing, Governor Northam on August 31 granted posthumous pardons to the Martinsville 7, seven young Black men who were tried, convicted, and sentenced to death in sham trials before all-white, all-male juries on charges of raping a white woman. They were executed in Virginia in 1951 in the largest mass execution for rape in U.S. history.

With Virginia’s abolition, a majority of U.S. states have now abolished the death penalty (23) or have a formal moratorium on its use (3). An additional ten states have not carried out an execution in at least ten years.

Justices of the Oregon Supreme Court

A judicial ruling in Oregon on October 8, 2021 is expected to clear much, if not all, of the state’s death row, rendering the death penalty functionally obsolete in the state. In 2019, the legislature narrowly limited the crimes for which the death penalty may be imposed. The Oregon Supreme Court, in its consideration of the appeal of death-row prisoner David Ray Bartol, found that his death sentence violated the state constitution’s ban on “disproportionate punishments” because the new law had reclassified his offense as non-capital. Because none of the people on Oregon’s death row committed crimes that are now defined as death-eligible, Jeffrey Ellis, co-director of the Oregon Capital Resource Center, said, “[m]y expectation is that every death sentence that is currently in place will be overturned.” Oregon has had a moratorium on executions for a decade, since then-Governor John Kitzhaber halted all executions on November 22, 2011.

Tennessee passed a bill closing a procedural loophole that had left death-row prisoners without any legal mechanism to enforce the U.S. Supreme Court’s 2002 ruling that the death penalty could not be used against people with intellectual disability. The bill, inspired by the case of Pervis Payne, created a post-conviction procedure for prisoners to file and obtain judicial review of claims that they are ineligible for the death penalty due to intellectual disability. Until this year, Tennessee law prevented death-row prisoners from presenting intellectual disability claims to state courts if their death sentences had already been upheld on appeal before the 2002 Supreme Court ruling. The bill was shepherded through the legislature by the Tennessee Black Caucus and passed with near-unanimous support. Lawyers for Payne, who is intellectually disabled and maintains his innocence, quickly filed a petition asking the Shelby County Criminal Court to “declare that Mr. Payne is ineligible to be executed because he is intellectually disabled.” After seeking for nearly 20 years to execute Payne without any judicial review of this issue, Shelby County prosecutors on November 18 conceded that he is intellectually disabled and not subject to the death penalty. They continue to oppose his innocence claim.

Ohio Governor Mike DeWine

Efforts to restrict or abolish the death penalty gained traction in two states with Republican-controlled legislatures: Ohio and Utah. Governor Mike DeWine signed a bipartisan bill on January 9 making Ohio the first state to bar the execution of defendants who were severely mentally ill at the time of the offense. The new law granted current death-row prisoners one year to file mental illness claims, and in June, David Braden became the first person removed from death row under the new policy. In February, bipartisan sponsors announced a death-penalty repeal bill, which has received committee hearings in both houses. The legislative session continues in 2022, when legislators may vote on the bill.

Republican legislators in Utah announced in September that they will introduce an abolition bill in the 2022 session. Senator David McCay, a sponsor of the bill and a former death-penalty supporter, said of capital punishment, “It sets a false expectation for society, sets a false expectation for the victims and their families, and increases the cost to the state of Utah and for states that still have capital punishment.”

In both Virginia and Utah, prosecutors and family members of homicide victims took leading roles in advocating for the end of the death penalty. Four Utah prosecutors, representing counties that comprise nearly 60% of the state’s population, released an open letter in support of abolition. Salt Lake County District Attorney Sim Gill, Grand County Attorney Christina Sloan, Summit County Attorney Margaret Olson, and Utah County Attorney David Leavitt — two Republicans and two Democrats — called capital punishment “a grave defect” in the operation of the law “that creates a liability for victims of violent crime, defendants’ due process rights, and for the public good.” They highlighted concerns about innocence and racial bias and said the death penalty has an “inherently coercive impact” on plea negotiations. “A defendant’s need to bargain for one’s very life in today’s legal culture … gives already powerful prosecutors too much power to avoid trial by threatening death,” their letter states.

Twelve Virginia prosecutors, representing about 40% of the population, similarly joined calls for abolition. “The death penalty is unjust, racially biased, and ineffective at deterring crime,” they wrote in a letter to legislative leaders. “We have more equitable and effective means of keeping our communities safe and addressing society’s most heinous crimes. It is past time for Virginia to end this antiquated practice.”

Rachel Sutphin

Virginia’s abolition movement also gained legislative support as a result of the efforts of Rachel Sutphin, the daughter of Corporal Eric Sutphin, who was murdered in 2006. Sutphin had unsuccessfully sought clemency for William Morva, her father’s killer, based upon concerns about Morva’s mental illness. Sutphin told the legislators that victims’ family members are revictimized and repeatedly retraumatized by the appeal process and do not receive solace from the prisoner’s execution. In Utah, Sharon Wright Weeks, whose sister and niece were murdered by severely mentally ill cult leader Ronald Lafferty, is urging legislators to repeal and replace the state’s death penalty. Like Sutphin, she said her family was “retraumatized” by having to relive the murders in Lafferty’s first trial, throughout the appeals process, and then again in a retrial after his conviction was overturned. Lafferty ultimately died on death row.

By contrast, some states made efforts to resume executions by adopting brutal execution methods or distorting the legal process. Arizona announced in June that it had “refurbished” its gas chamber and would seek to carry out executions using cyanide gas, the same gas used by the Nazis to murder more than one million men, women, and children during the Holocaust. The announcement drew international backlash and condemnation.

South Carolina attempted to resume executions after a ten-year hiatus, scheduling one execution for February and another for May even though the state had no drugs to carry them out. The South Carolina Supreme Court vacated the execution notices and ordered the state to not issue another death warrant until one of three scenarios took place: the state confirms to the court that the Department of Corrections has the ability to carry out a lethal-injection execution, a death-row prisoner elects to be electrocuted instead, or the law changes to otherwise allow executions to take place. In response, the South Carolina legislature passed a bill in May 2021 making electrocution the default method of execution, with lethal injection or firing squad available as alternatives. The state immediately set two execution dates for June 2021, without having offered the men set for execution an opportunity to elect their method of execution. The South Carolina Supreme Court once again halted the executions, saying that the state had violated the prisoners’ “statutory right … to elect the manner of their execution.” The court also noted that the state had not yet developed a protocol for executions by firing squad and barred the state from setting any execution dates until a protocol is developed.

State Officials and Prosecutors Who Interfered with Legal Process

Prosecutors and state officials also engaged in questionable acts in 2021 that interfered with or undermined the legal process in death-penalty cases. Prosecutors secretly served as law clerks in cases they prosecuted without disclosing their conflicts of interest. Legislators in Nevada who worked full time as prosecutors blocked votes on an abolition bill opposed by their office. And officials in Florida, Missouri, Tennessee, and Oklahoma used their positions to attempt to intimidate parole board members or locally elected reform prosecutors or override their decisions.

Clinton Young

Prosecutorial conflicts of interest were discovered in two separate cases this year, one in Texas and one in Tennessee. The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals vacated the conviction of death-row prisoner Clinton Young because the prosecutor who tried him was simultaneously on the payroll of the judge who presided over the trial and decided Young’s trial court appeals. “Judicial and prosecutorial misconduct — in the form of an undisclosed employment relationship between the trial judge and the prosecutor appearing before him — tainted Applicant’s entire proceeding from the outset,” the court wrote. “The evidence presented in this case supports only one legal conclusion: that Applicant was deprived of his due process rights to a fair trial and an impartial judge.”

A similar problem appeared to be present in the case of Pervis Payne in Tennessee. In October, his attorneys sought a hearing to determine whether the Shelby County District Attorney’s office should be recused from his case because of an undisclosed conflict involving Assistant District Attorney General Stephen Jones. Payne’s attorney presented evidence suggesting that Jones may have represented the prosecution in Payne’s case while simultaneously working as a capital case staff attorney, assisting the county’s judges on death penalty cases during the time that Payne’s challenges to his conviction and death sentence were pending in the Shelby County courts.

Two Las Vegas prosecutors who hold legislative leadership positions in the Nevada state senate blocked movement on a death-penalty abolition bill in that state. Clark County District Attorney Steve Wolfson, who runs the office in which the two senators work when the legislature is not in session, was the lead witness against the bill in the Assembly. Over Wolfson’s opposition, the bill passed the state Assembly with a 26 – 16 vote and repeal advocates believed they had sufficient votes for passage in the Senate. However, they were unable to get a hearing or a vote on the bill in the Senate Judiciary Committee, which was chaired by Senator Melanie Scheible, a prosecutor in Wolfson’s office. Despite the significant margin for repeal in the state Assembly, Senate Majority Leader Nicole Cannizzaro, who is also a Clark County prosecutor, said legislators could not reach consensus on possible amendments, so the bill would not advance in the Senate. Shortly after the Assembly passed the bill, and while it was pending in the Senate, Clark County prosecutors filed pleadings to set an execution date for Nevada death-row prisoner Zane Floyd. Wolfson said the timing of the execution request was coincidental.

Abu-Ali Abdur’Rahman

State officials across the country intervened to block the actions of locally elected prosecutors in several death-penalty cases. A Nashville judge approved a plea deal for the second time to resentence death-row prisoner Abu-Ali Abdur’Rahman to life without parole. Abdur’Rahman’s 1987 conviction was tainted by former Davidson County Assistant District Attorney General John Zimmerman’s unconstitutional use of discretionary strikes to remove African Americans from the jury. Abdur’Rahman had agreed to a plea deal with Davidson County District Attorney General Glenn Funk in 2019, but Tennessee Attorney General Herbert H. Slatery III intervened in the case, claiming that Funk and the trial court had no authority to vacate Abdur’Rahman’s sentence in the absence of a proven constitutional violation. Abdur’Rahman was procedurally barred from claiming jury discrimination in his case, Slatery said. After the Tennessee Court of Criminal Appeals struck down the first plea deal, Abdur’Rahman’s attorneys argued that new evidence of discriminatory jury selection allowed him to challenge his conviction. Funk agreed, telling the court that the state’s “interest in the finality of convictions and sentences is outweighed by the interests of justice, and in some situations by recognition of the sanctity of human life.” On December 10, Slatery announced he will not appeal the latest plea deal, finalizing Abdur’Rahman’s removal from death row.

In Missouri and Florida, state attorneys general intervened to block local prosecutors from advancing potential exonerations. Under a Missouri law passed in April 2021, county prosecutors may file motions to free prisoners they believe to be innocent. Jackson County Prosecutor Jean Peters Baker filed such a motion in the case of Kevin Strickland, who was capitally tried and ultimately sentenced to life without parole for a 1978 triple murder. Strickland’s innocence claims were supported not only by Peters Baker’s office, but by the two other men convicted of the crime, the lone eyewitness, and several state legislators. At a November hearing, the Jackson County Prosecutor’s office and the Missouri Attorney General’s office, which would typically be allied in a criminal case, were adversaries. In an attempt to prevent Jackson County prosecutors from presenting new evidence of innocence, the attorney general’s office filed a motion to limit the evidence the court could consider to the evidence that been presented to jurors in Strickland’s initial trial. When that failed, they moved to substitute themselves for local prosecutors as counsel for the state and to exclude Strickland from participating as a party in his own innocence hearing. The court rejected that motion as well and ultimately issued an order exonerating Strickland.

Florida Attorney General Ashley Moody also intervened in two cases involving potentially innocent death-row prisoners, filing motions to block DNA testing that State Attorney Monique H. Worrell had consented to and that the trial court had approved. Worrell had agreed to testing in the cases of Tommy Zeigler and Henry Sireci, both of whom were sentenced to death in 1976 for unrelated crimes and both of whom had consistently maintained their innocence for more than forty years. Moody argued that the state DNA law erected limits on when DNA testing could be performed and denied local prosecutors discretion to consent to DNA testing without the approval of state prosecutors, and that Ziegler’s and Sireci’s requests for testing did not meet the requirements of Florida state post-conviction law. She failed to note that years earlier, less sophisticated DNA testing had been conducted under a similar agreement without any objection from the attorney general’s office. The trial court refused to rescind its order, and Moody has further delayed the testing by filing an appeal.

In Oklahoma, prosecutors repeatedly attempted to manipulate the clemency process by trying to recuse members of the state’s pardons and parole board who they believed would favor death-row prisoner Julius Jones. In the spring of 2020, the pardons board indicated that it would be receptive to requests from death-row prisoners to consider petitions for commutation before death warrants had been issued in their cases. However, as a later investigation by The Frontier discovered, former judge Allen McCall — then a member of the board — had threatened the board’s executive director, Steven Bickley, with a grand jury investigation if he scheduled a hearing for Jones without first obtaining approval from then-Attorney General Mike Hunter. In June 2020, the board formally asked Hunter if it had the authority to conduct pre-warrant commutation hearings for death-row prisoners. Hunter agreed that the board had the authority to conduct such hearings, but Bickley subsequently resigned, saying he had been “threatened for doing his job.”

Julius Jones

Prior to Jones’ commutation hearing, Oklahoma County District Attorney David Prater filed an emergency motion with the Oklahoma Supreme Court to recuse two members of the board, alleging that they would be biased in favor of commutation because of their ties to organizations that seek to reduce incarceration rates. The court denied the motion, writing that Prater was “asking this Court to provide for a remedy that simply does not exist under Oklahoma law.” The board voted 3 – 1 to recommend that Governor Kevin Stitt commute Jones’ sentence to a parole-eligible life term.

After that recommendation, Oklahoma Attorney General John O’Connor sought and obtained a death warrant for Jones. Governor Stitt then indicated he would not act on the board’s recommendation until it conducted a separate clemency hearing at which Jones and family members of murder victim Paul Howell would testify. Prior to that clemency hearing, O’Connor filed a new motion in the Oklahoma Supreme Court, attempting to recuse the same two board members on the same previously rejected grounds. The court again denied the recusal request and the board, once again by a 3 – 1 vote, recommended clemency. Four hours before Jones’ scheduled execution, Governor Stitt issued an order commuting Jones’ death sentence to life without parole, conditioned upon Jones never seeking a future pardon or further commutation of his sentence.

Federal Death Penalty Top

Key Findings

- Federal execution spree ends less than one week before Biden inauguration

- Six federal executions performed between election and inauguration are the most ever in a presidential transition period

- Attorney General Merrick Garland announces pause on federal executions, DOJ will review Trump policies

The change of presidential administration had major effects on the use of the federal death penalty, bringing Department of Justice (DOJ) practices back in line with those of other modern presidencies. The Trump administration concluded its unprecedented execution spree just four days before President Biden was inaugurated. The thirteen federal executions performed in a six-month period were procedurally and historically anomalous and marked the federal government as an outlier in its use of the death penalty.

Attorney General Merrick Garland

Although Biden had campaigned on a promise to try to end the federal death penalty, his administration took no affirmative steps to do so. Attorney General Merrick Garland issued a memorandum announcing that DOJ would not seek new execution dates while it reviewed changes in death-penalty policies implemented under the former administration, but it also took steps to defend or reinstate federal death sentences in two notorious cases.

The executions of Lisa Montgomery, Corey Johnson, and Dustin Higgs in January 2021 concluded an unprecedented thirteen-execution spree undertaken by the federal government. In performing the executions, the Trump administration deviated dramatically from historical norms and practices. The six executions between the November 3, 2020 election and the January 20, 2021 inauguration were the most in U.S. history during a presidential transition period. The executions were performed during the worst pandemic in more than a century, flouting public health safeguards that led every U.S. state to pause executions. All 13 federal executions took place during the longest pause between state executions in more than forty years.

Throughout the federal execution spree, the conduct of the DOJ and the U.S. Supreme Court ran counter to both long-established norms and recent national trends. While death sentences and executions hovered near historic lows for the seventh consecutive year, and public support for the death penalty remained at its lowest level in half a century, the Department of Justice performed the most federal civilian executions in any single year since 1896. Among those executed were two people accused of murders committed in their teens, two prisoners with strong evidence of intellectual disability, two severely mentally ill prisoners, one prisoner who undisputedly was not the triggerman, and two prisoners who had contracted COVID-19 in the weeks leading up to their executions.

The Supreme Court intervened to lift stays and injunctions imposed by lower courts, foreclosing opportunities for judicial review of weighty claims of intellectual disability, competency to be executed, and challenges to the federal government’s execution protocol that the lower federal courts had found were likely to succeed. Four of the executions took place after the midnight expiration of the prisoners’ execution warrants, because the Supreme Court acted to lift lower court stays late at night. In those executions, the Federal Bureau of Prisons issued unprecedented and legally suspect same-day execution notices and proceeded to execute the prisoners within a few hours.

On June 30, Attorney General Merrick Garland announced a formal pause on all federal executions while the Department of Justice undertook a review of changes in executive branch death-penalty policies implemented under the Trump DOJ. The announcement marked the Biden administration’s official departure from the outlier practices of the Trump administration. “The Department of Justice must ensure that everyone in the federal criminal justice system is not only afforded the rights guaranteed by the Constitution and laws of the United States, but is also treated fairly and humanely. That obligation has special force in capital cases,” Garland wrote. The memorandum did not address the administration’s policy on continuing to seek new death sentences or oppose appeals filed by current death-row prisoners.

Dzhokhar Tsarnaev

In the months after the announcement, the DOJ withdrew a number of notices of intent to seek the death penalty that had been filed under the previous administration. However, DOJ continued to defend previously imposed death sentences, and its actions in the cases of Dylann Roof and Dzhokhar Tsarnaev showed a willingness to do so aggressively, at least in the most nationally prominent federal cases. In August, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit affirmed Roof’s federal-court convictions and death sentences for the racially motivated murders of nine parishioners in an historic Charleston, South Carolina African-American church in 2017. The DOJ had defended Roof’s convictions and death sentences at the Fourth Circuit. In October, the U.S. Supreme Court heard oral argument in the case of Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, who was convicted of the 2013 Boston Marathon bombing. In 2020, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the First Circuit had vacated Tsarnaev’s conviction, but the DOJ opted to continue the Trump administration’s appeal of that decision and argue in favor of reinstating the death sentence.

A White House spokesperson disassociated the President from the DOJ’s Tsarnaev appeal, citing the Justice Department’s “independence regarding such decisions.” In an email to reporters on June 15, Deputy White House Press Secretary Andrew Bates wrote, “President Biden has made clear that he has deep concerns about whether capital punishment is consistent with the values that are fundamental to our sense of justice and fairness. … The President believes the Department should return to its prior practice, and not carry out executions.”

Legislation to abolish the federal death penalty was introduced in the U.S. Congress, and legislators in both the House and the Senate wrote letters to Attorney General Garland urging him to stop seeking death sentences and asked President Biden to use his executive power to commute federal death row. The White House offered no substantive comment on either request.

Execution and Sentencing Trends Top

Key Findings

- Seventh consecutive year with fewer than 50 new death sentences and 30 executions

- Use of the death penalty is increasingly geographically concentrated: three states accounted for majority of executions and death sentences

- Just five counties now account for more than 20% of all U.S. executions

Executions By State

| State | 2021 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|

| U.S. Government | 3 | 10 |

| Texas | 3 | 3 |

| Oklahoma | 2 | |

| Alabama | 1 | 1 |

| Mississippi | 1 | |

| Missouri | 1 | 1 |

| Georgia | 1 | |

| Tennessee | 1 | |

| Total | 11 | 17 |

The combined impact of the continuing COVID pandemic and dwindling support for capital punishment made 2021 the seventh consecutive year with fewer than 30 executions and 50 new death sentences in the United States. The 11 executions carried out during the year were the fewest since 1988, and the eight state executions were the second fewest since 1983, one more than the 37-year low of seven state executions in 2020. The number of new death sentences tied last year’s record low, with just 18 imposed across the country.

Just five states and the federal government conducted executions in 2021. Texas and the U.S. government each executed three people, Oklahoma executed two, and three additional states — Alabama, Mississippi, and Missouri — each executed one person.

Racial disparities in executions and new death sentences persisted in 2021, as six of the eleven people executed were Black (54.5%). Half of the Black prisoners executed were put to death for interracial murders, but every white prisoner was executed for the murder of a white victim. The majority (61.1%) of people sentenced to death in 2021 were either Black or Latinx. No white defendant was sentenced to death in trial proceedings that did not involve any white victim.

Seven states imposed new death sentences in 2021. Oklahoma and Alabama each handed down four new sentences, although no jury in Alabama unanimously recommended the death penalty. California and Texas each imposed three death sentences. Florida imposed two. Two states – Nebraska and Tennessee — imposed one death sentence each. Only two U.S. counties — Los Angeles County, California and Oklahoma County, Oklahoma — were responsible for more than a single death sentence. The two sentences imposed in Los Angeles both resulted from jury verdicts handed down before the county elected reform prosecutor George Gascón, who has pledged not to seek the death penalty. The final judicial sentencings in those cases had been delayed by the pandemic. One death sentence in Florida was also the result of pandemic-delayed court proceedings, after a jury recommended a death sentence in 2019.

Counties With the Most Death Sentences in the Last Five Years

| County | State | New Death Sentences 2017 – 2021 | New Death Sentences 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Riverside | California | 10 | |

| Maricopa | Arizona | 6 | |

| Los Angeles | California | 5 | 2 |

| Cuyahoga | Ohio | 5 | |

| Clark | Nevada | 4 | |

| Oklahoma | Oklahoma | 4 | 2 |

| Tulare | California | 4 | 1 |

Notably, there were no death sentences in many formerly heavy-use death-penalty counties, including Harris County, Texas; Philadelphia County, Pennsylvania; and Duval County, Florida. The election of reform prosecutors in those and other counties across the country has contributed significantly to the continuing low number of new death sentences.

The states responsible for the year’s executions were, in large part, also responsible for the new death sentences. Alabama, Texas, and Oklahoma collectively accounted for 54.5% of the year’s executions and 61.1% of the year’s new death sentences. Oklahoma has surpassed Virginia as the state with the second-most executions since 1976.

At the county level, five U.S. counties (Harris, Dallas, Tarrant, and Bexar counties in Texas and Oklahoma County, Oklahoma) now account for 20% of all executions in the U.S. since 1976. Oklahoma County, one of only two U.S. counties to impose more than one death sentence in 2021, has performed more executions than any county outside of Texas. With 42 executions, it has carried out more than twice the number of executions of the next-highest county (St. Louis County, Missouri, with 19).

Fewer than one quarter of the executions scheduled in 2021 were carried out. Of the 45 execution dates that were set, 11 (24.4%) resulted in executions. One person, Julius Jones, received a commutation of his death sentence. One person with an execution date this year, James Frazier of Ohio, died on death row. Frazier, Ohio’s oldest death-row prisoner, was one of at least 136 Ohio prisoners to die of COVID-19 since the pandemic began. Governor Mike DeWine granted reprieves to an additional nine Ohio prisoners, citing problems with Ohio’s lethal-injection protocol and the risk to the state’s access to therapeutic medicines if the state diverted drugs intended for public health purposes for use in executions. One reprieve was granted in Pennsylvania, where Governor Tom Wolf has imposed a moratorium on executions.

One-third of all scheduled executions (15 of 45) were stayed by the courts. Three prisoners in Texas received stays to allow time for consideration of their claims of intellectual disability. Another two, also in Texas, were granted stays while the U.S. Supreme Court considers whether Texas’ execution policies violate prisoners’ religious liberty. Executions in Nevada and South Carolina were stayed over concerns about methods of execution. An Idaho court stayed the execution of terminally ill prisoner Gerald Pizzuto so the state pardons board could consider his application for clemency.

Seven additional death warrants were removed, withdrawn, vacated, or rescheduled.

Though few jurisdictions performed or even scheduled executions in 2021, those that did undertook extreme measures that demonstrated a lack of concern for due process and a cavalier inattentiveness to execution preparation. South Carolina twice attempted to schedule executions without obtaining execution drugs or establishing a legally required protocol for executions by firing squad. Oklahoma set seven execution dates despite a pending trial on the constitutionality of the state’s lethal-injection protocol and a prior representation by the state attorney general that the state would not seek execution dates until the lethal-injection issues were resolved.

Arizona prosecutors attempted to resume executions by asking the Arizona Supreme Court to set expedited filing deadlines in advance of issuing execution warrants for two prisoners. These limitations would require prisoners to present and courts to resolve challenges to Arizona’s lethal-injection protocol and other legal issues within the 90-day window before the pentobarbital the state had spent $1.5 million to obtain went bad. The compressed schedule was necessary, they argued, so the state could obtain death warrants, have the drug manufactured by a compounding pharmacy, get the drug tested, and carry out each execution before the drug lost its potency. The prisoners objected that Arizona had misrepresented the shelf life of the compounded drug, citing medical journals and scientific experts who said compounded pentobarbital loses potency after 45 days. In response, prosecutors admitted their mistake and asked the court to limit the time for judicial review even further so the executions could move forward — a proposal that would give the prisoners just four days to respond to a motion to set an execution date. The Arizona Supreme Court then vacated the briefing schedule, requiring prosecutors to conduct “specialized testing to determine a beyond-use date for compounded doses of the drug” before renewing its scheduling motion.

In May, Idaho scheduled the execution of a hospice-bound terminally ill prisoner while his petition for a hearing before the Idaho Commission of Pardons and Parole was pending. After the commission agreed to hear the case and set a November hearing date, the trial court granted a stay “until the conclusion of the commutation proceedings.” Nevada also prematurely set an execution date for Zane Floyd, which was stayed because the state failed to disclose the drugs it intended to use in its never-before-tried execution protocol in sufficient time for the court to review the constitutionality of the protocol. Drug manufacturer Hikma Pharmaceuticals threatened to sue the state for illegally obtaining its drugs for use in the execution. Courts had previously blocked Nevada’s attempt to execute Scott Dozier with drugs the court said had been purchased in “bad faith” through “subterfuge.” Advocates for the repeal of the state’s death penalty questioned the timing of the execution warrant, which prosecutors requested while the state legislature was considering an abolition bill.

Innocence and Clemency Top

Key Findings

- Two more death-row prisoners exonerated in 2021, and DPIC review of death sentences imposed since 1972 revealed 11 additional exonerations, bringing to 186 the number of death-row exonerees since 1973

- Since 1973, one wrongfully convicted death-row prisoner has been exonerated for every 8.3 executions

- States and counties paid out close to $100 million in payments for wrongful capital convictions

- Julius Jones and Pervis Payne released from death row in 2021 but still face life in prison

Exonerations in 2021

The public’s understanding of the grave dangers of wrongful capital convictions and death sentences deepened in 2021 as two innocent prisoners were exonerated more than 25 years after being wrongfully sentenced to die, and a multi-year Death Penalty Information Center review of more than 9,600 death sentences imposed since 1972 discovered 11 previously unreported death-row exonerations. The now 186 death-row exonerations since 1973 revealed that the American death-penalty system is even more frighteningly unreliable than was previously understood. The data now show that one person wrongfully convicted and condemned to die has been exonerated for every 8.3 prisoners who have been executed.

DPIC’s February 2021 special report, The Innocence Epidemic, analyzed the factors contributing to those wrongful capital convictions and the exoneration process. The report found that wrongful capital convictions cannot be dismissed as mere accidental failures of the justice system. Instead, most involve a combination of police or prosecutorial misconduct and perjury or false accusation. The data further showed that innocent Black defendants were more likely to be wrongfully convicted and condemned and were more likely to spend more time imprisoned before being exonerated. The report also found that wrongful capital convictions occurred all over the country, but were most likely in outlier counties that most aggressively pursued death sentences and in states with outlier sentencing practices such as non-unanimous jury recommendations for death and judicial override of jury recommendations for life.

Both death-row exonerations in 2021 involved cases from Mississippi, and both involved false forensic testimony.

Eddie Lee Howard, Jr.

Eddie Lee Howard, Jr., convicted and sentenced to death based on the false forensic testimony of a since disgraced prosecution expert witness, was exonerated in January 2021. He was the sixth death-row prisoner exonerated in Mississippi since 1973.

Howard spent 26 years on death row on charges that he murdered and allegedly raped an 84-year-old white woman. He was first convicted and sentenced to death in 1994 in a trial in which he represented himself. The Mississippi Supreme Court overturned that conviction in 1997 and ordered a new trial. He was convicted and sentenced to death again in a retrial in 2000 at which forensic odontologist Dr. Michael West testified that Howard was the source of bite marks he claimed to have found on the victim’s body during a post-autopsy, post-exhumation examination of her body. The initial autopsy report did not mention bite marks but claimed that the victim had been beaten, strangled, stabbed, and raped.

During post-conviction evidentiary hearings in 2016, Howard’s lawyers presented DNA evidence that eviscerated the prosecution’s false forensic testimony. DNA testing showed no evidence of semen or male DNA on the victim’s clothing, bedsheets, or body and no male DNA on the locations on the victim’s body where she supposedly had been bitten. None of the blood or other items tested contained Howard’s DNA. Male DNA found on the knife used by the murderer excluded Howard as the source.

Howard was represented by lawyers from the Mississippi Innocence Project and the national Innocence Project. “I want to say many thanks to the many people who are responsible for helping to make my dream of freedom a reality,” said Howard after his exoneration. “I thank you with all my heart, because without your hard work on my behalf, I would still be confined in that terrible place called the Mississippi Department of Corrections, on death row, waiting to be executed.”

Sherwood Brown

In August 2021, Sherwood Brown was exonerated of a triple murder that sent him to Mississippi’s death row in 1995.

Brown was sentenced to death for the murder of 13-year-old Evangela Boyd and received two life sentences for the murders of her mother and grandmother. His convictions and death sentence rested in substantial part on false expert forensic testimony, as well as the perjured testimony of a jailhouse informant. The informant was facing serious charges for car theft when he claimed Brown had confessed to the murders. Prosecutors argued that blood found on the sole of one of Brown’s shoes came from the victims, and two forensic bitemark analysts falsely claimed that a cut on Brown’s wrist was a bitemark that matched the girl’s bite pattern.

DNA evidence later contradicted the prosecution’s narrative. The evidence showed that bloody footprints in and around the murder scene contained only female DNA and the blood spot on Brown’s shoe contained only male DNA. DNA testing on a swab of Boyd’s saliva did not contain Brown’s DNA, refuting the claim that she had bitten Brown. DNA tests on the sexual assault kit collected during the autopsy found no DNA from Brown but showed that Evangela Boyd’s pubic hair and her bra contained DNA from unidentified males. A forensic scientist from the Mississippi Crime Laboratory found that none of the hair evidence recovered from the clothing and bodies of the victims had any microscopic characteristics similar to Brown’s hair. A crime lab fingerprint analyst also found that none of the fingerprints found at the scene belonged to Brown.

Based on this evidence, the Mississippi Supreme Court overturned Brown’s conviction and death sentence in October 2017. However, Brown remained in custody facing possible capital retrial as prosecutors attempted to build another case against him. With Brown in county pretrial custody, four more laboratories tested the DNA evidence over the course of three more years. Each came back with the same results. “Every time, there was nothing incriminating Sherwood,” said one of Brown’s attorneys after his exoneration. “The state was trying to find something to incriminate Sherwood, but every time they did, it kind of stumped them deeper.”

Finally, on August 24, Mississippi Circuit Court Judge Jimmy McClure granted a prosecution motion to dismiss charges against Brown. He was released later that day after having spent 26 years on death row or facing the prospects of a capital retrial.

Court Decisions in Potential Exoneration Cases

Crosley Green

More than thirty years after a Florida judge sentenced him to death following an 8 – 4 sentencing recommendation by an all-white jury, Crosley Green was freed in April 2021. Citing Green’s age and health risks related to continued incarceration during the pandemic, a judge of the U.S. District Court for the Middle District of Florida ordered Green’s immediate release while a federal appeals court considers prosecutors’ appeal of the district court’s July 2018 decision overturning his conviction.

Green, who is Black, was convicted and sentenced to death in 1990 for the 1989 murder of Charles “Chip” Flynn. No physical evidence linked him to the crime, and the one witness to the crime was the victim’s ex-girlfriend, who first responders initially identified as the likely perpetrator. The two police officers who responded to the crime scene told prosecutors they believed the ex-girlfriend had killed Flynn, but prosecutors withheld their notes from Green’s defense team, denying him access to potentially exculpatory evidence. All three witnesses who testified that Green had confessed to the murder later recanted their statements, saying they had been coerced by prosecutors. In 2007, the trial court overturned Green’s death sentence. The court found that trial counsel had failed to investigate court records that would have disproven the prosecution’s claim that Green had a previous conviction in New York for a crime of violence. The Florida Supreme Court upheld that ruling in 2008 and Green was resentenced to life before being released this year.

Clinton Young

The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals (TCCA) in September 2021 vacated the conviction of death-row prisoner Clinton Young, whose prosecutor was also on the payroll of the judge who presided over the trial and decided his trial court appeals. In granting Young’s petition for a new trial, the TCCA wrote: “Judicial and prosecutorial misconduct — in the form of an undisclosed employment relationship between the trial judge and the prosecutor appearing before him — tainted Applicant’s entire proceeding from the outset. … The evidence presented in this case supports only one legal conclusion: that Applicant was deprived of his due process rights to a fair trial and an impartial judge.”

Young was convicted and sentenced to death by a Midland County jury in 2003 on charges that he had murdered two men for use of their vehicles during a 48-hour crime spree. He has long said he was framed for the murders. Assistant District Attorney Ralph Petty was one of the prosecutors in Young’s case, while at the same time serving as a paid law clerk to state District Court Judge John Hyde. In that dual role, Petty conducted research and made legal recommendations to the court on the same motions the prosecution had filed or were opposing in the case. Neither Petty, nor Hyde, nor the Midland County District Attorney’s office disclosed this conflict to the defense. Petty has since been barred from the continued practice of law.

Rodney Reed

After being directed by the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals (TCCA) to review Rodney Reed’s claim that he was innocent of the 1996 murder of Stacey Stites, a Texas district court judge recommended that Reed’s conviction be upheld. In a November 1, 2021 decision, Bastrop County District Court Judge J.D. Langley issued recommendations and findings of fact that credited every prosecution witness over every witness presented by Reed’s defense counsel.

The TCCA had stayed Reed’s execution on November 15, 2019, less than one week before he was scheduled to be put to death and returned his case to the Bastrop County district court to review Reed’s claims that prosecutors presented false testimony and suppressed exculpatory evidence and that Reed is actually innocent. The appeals court retained jurisdiction over the case and directed the trial court to make recommendations on how it should rule in the case.

During a ten-day evidentiary hearing, Reed’s lawyers presented evidence that Reed, who is Black, was having an affair with Stites, who is white; that Stites was actually murdered by her abusive fiancé, Jimmy Fennell; and that Fennell, who at that time was a police officer in Giddings, Texas, had framed Reed for the murder. Numerous witnesses testified that they had seen Stites together with Reed on prior occasions, heard Fennell threaten to kill her if she cheated on him, and heard Fennell admit to the killing. Two forensics experts testified that Stites died hours earlier than the prosecution had claimed, at a time that Fennell had said she was with him. Fennell took the stand and denied that he had committed the killing.

Langley accepted Fennell’s testimony on every disputed issue over the contrary testimony of a dozen separate defense witnesses. The court also rejected Reed’s challenges that prosecutors presented false forensic testimony, crediting the trial testimony of the prosecution’s local forensic examiners over that of Reed’s nationally known forensic experts. The county court transmitted its findings and recommendations to the TCCA, which will consider Judge Langley’s recommendation, but make its own final ruling. Reed’s lawyers continue to pursue relief, citing the unreliability of the evidence against Reed, as well as racial bias during his trial.

Wrongful Capital Prosecutions

Dennis Perry

Dennis Perry was exonerated this year of the racially motivated murders of a deacon and his wife in a Black church in Georgia in 1985. His case was one of at least four death-penalty prosecutions involving misconduct by Brunswick Judicial Circuit Assistant District Attorney John B. Johnson III. Johnson obtained death sentences against death-row exonerees Larry Jenkins and Larry Lee, as well as Jimmy Meders, whose death sentence was commuted in 2020.

Johnson had capitally prosecuted Perry even after the lead investigators in the case had determined he could not have been at the church at the time of the murders. Johnson presented testimony from the mother of Perry’s ex-girlfriend, claiming he had told her he planned to kill one of the victims. Johnson withheld evidence from the defense that the witness was to receive $12,000 in reward money for her testimony. New DNA evidence implicated an alternate suspect, an alleged white supremacist who an Atlanta Journal-Constitution investigation showed had bragged that he had “killed two ni****rs“ and had manufactured a false alibi for the murders.

When he stood with his defense team on the steps of the Brunswick, Georgia courthouse after a trial judge dismissed all charges against him, Perry was a free man.

Kevin Strickland

In November 2021, a Missouri judge released Kevin Strickland from prison more than 42 years after his wrongful capital murder conviction in June 1979. No physical evidence linked Strickland to the 1978 Kansas City triple murders for which he was convicted; two other men convicted of the killings later named other participants in the offense but said Strickland was not involved; and the lone eyewitness who testified against him said she had been pressured by police to falsely implicate Strickland.

Strickland initially rejected a plea deal in his case and faced a possible death sentence, believing the system would acquit him. At an innocence hearing authorized by a new Missouri law, he testified, “I wasn’t about to plead guilty to a crime I had absolutely nothing to do with. Wasn’t going to do it … at 18 years old, and I knew the system worked, so I knew that I would be vindicated, I wouldn’t be found guilty of a crime I did not commit. I would not take a plea deal and admit to something I did not do.” Strickland, who is Black, was capitally tried twice for the murders. The jury in his first trial deadlocked at 11 – 1 for conviction, with the only Black juror holding out for acquittal. Strickland was convicted of one count of capital murder and two counts of second-degree murder by an all-white jury in his second trial. After he was convicted, the prosecution withdrew the death penalty from his case.

Speaking to reporters outside the Western Missouri Correctional Center following his release, Strickland — now 62 and in a wheelchair following several heart attacks — said he was attempting to process a range of emotions. “I’m not necessarily angry. It’s a lot,” he said. “Joy, sorrow, fear. I am trying to figure out how to put them together.” He said he would like to become involved in efforts to reform the criminal legal system to “keep this from happening to someone else.”

2021 Payouts Expose the Collateral Costs of Wrongful Capital Convictions

Taxpayer payouts in 2021 from police and prosecutorial misconduct associated with the wrongful use or threatened use of the death penalty exposed a previously hidden collateral cost of capital punishment: the cost of liability. In 2021, multiple death-row exonerees won lawsuits against or received compensation awards from jurisdictions that wrongfully sentenced them to death, and multiple exonerees have lawsuits still pending against the jurisdictions and various officials involved in their wrongful convictions.

Henry McCollum and Leon Brown

In May 2021, half-brothers Henry McCollum and Leon Brown were each awarded $31 million, $1 million for each year they spent in prison in North Carolina, plus an additional $13 million in punitive damages. McCollum and Brown were 19 and 15, respectively, when they were arrested in 1983 on charges of raping and murdering 11-year-old Sabrina Buie. They were coerced into confessing, and police fabricated evidence against them while suppressing or ignoring evidence of their innocence. In 2014, they were exonerated after DNA evidence implicated Roscoe Artis, who has been convicted of a similar crime. McCollum and Brown’s youth and intellectual disabilities made them particularly vulnerable to manipulation and coercion by police.

Joe D’Ambrosio

In August 2021, the Ohio Controlling Board voted unanimously to award Cleveland death-row exoneree Joe D’Ambrosio $1 million in compensation from the state’s wrongful imprisonment fund for his wrongful convictions. D’Ambrosio was convicted of burglary, kidnaping, felony murder, and the aggravated murder of teenager Tony Klann in 1989.

In early September 2021, former death-row prisoner Robert Miller reached a $2 million settlement with Oklahoma City for his wrongful conviction and death sentence for the rape and murder of two elderly women in Oklahoma County in 1988.

Both D’Ambrosio and Miller were tried and convicted in counties with long histories of prosecutorial misconduct and high rates of wrongful capital convictions. The compensation comes more than a decade after each was released from incarceration.

Curtis Flowers

Multiple lawsuits brought by other death-row exonerees and exonerees who were threatened with the death penalty during their prosecutions are pending across the country. Former Mississippi death-row prisoner Curtis Flowers, who was exonerated in 2020, is suing the officials whose misconduct led to his arrest and repeated wrongful convictions. Flowers was tried six times and spent 23 years wrongfully incarcerated for a quadruple murder in a white-owned furniture store in Winona, Mississippi.

Robert DuBoise

Florida death-row exoneree Robert DuBoise is suing the City of Tampa, four Tampa police officers, and the forensic odontologist who falsely testified against him, alleging that they fabricated evidence that led to his wrongful conviction and death sentence. DuBoise was exonerated in August 2020 after a Conviction Integrity Unit reviewed his case and new DNA evidence excluded him as the perpetrator of the rape and murder for which he was wrongfully convicted and sentenced to death 37 years earlier. DuBoise’s conviction was based on junk-science bite-mark evidence and false testimony from a prison informant.

In May 2021, Pennsylvania exoneree Theophalis Wilson filed a civil rights suit against Philadelphia following discovery by the Philadelphia District Attorney’s Conviction Integrity Unit that the prosecution’s lead witness had falsely testified against Wilson after homicide detectives threatened him with the death penalty. The Philadelphia Inquirer reported in June that the City of Philadelphia had paid $34 million since 2018 to six exonerees who had been wrongfully prosecuted for murder, and that 20 more people, including multiple death row exonerees, had either filed lawsuits or are within the statute of limitations to do so. On November 23, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit ruled in favor of former Philadelphia death-row prisoner Jimmy Dennis, who pleaded no contest to a murder he did not commit so that he could obtain his release from prison and avoid a possible capital retrial, that the police officers who withheld exculpatory evidence and planted evidence against him in his capital trial were not protected by qualified immunity for their actions.

Innocent, Spared Execution, But Now Sentenced to Life In Prison

Two nationally known prisoners with significant innocence claims, Julius Jones and Pervis Payne, were removed from death row in 2021 but remain imprisoned for life. On November 18, Oklahoma Governor Kevin Stitt commuted Jones’ death sentence to life without parole. That same day, the Shelby County District Attorney’s office conceded that Payne is intellectually disabled and ineligible for the death penalty. The trial court vacated his death sentence and removed him from death row on November 23.

Pervis Payne hugs his lawyer, Assistant Federal Defender Kelley Henry, after a Tennessee judge removed him from death row.

Pervis Payne was convicted and sentenced to death in Memphis, Tennessee in 1988 on charges that he murdered Charisse Christopher and her 2‑year-old daughter, Lacie, and seriously wounded her 3‑year-old son, Nicholas. He was prosecuted by the Shelby County District Attorney’s office in a county that had the most known lynchings in the state of Tennessee and was responsible for nearly half of its death sentences. A July 2017 report by Harvard University’s Fair Punishment Project, The Recidivists: New Report on Rates of Prosecutorial Misconduct, highlighted Shelby County District Attorney Amy Weirich for withholding key evidence from the defense and making improper arguments.

The investigation and prosecution of Payne’s case was repeatedly infected by racial bias. Payne told his sister that while police were interrogating him, they said to him: “you think you black now, wait until we fry you.” In a trial tainted by prosecutorial misconduct, county prosecutors asserted without evidence that Payne, a young Black man, was on drugs and stabbed a white woman to death because she spurned his sexual advances.

Payne, the son of a minister, did not use drugs, and police refused his mother’s request to conduct a blood test to prove he had no drugs in his system. Prosecutors also falsely asserted that Payne had sexually assaulted Christopher, showing the jury a bloody tampon that they asserted he had pulled from her body. However, the tampon did not appear in any of the police photos or video taken at the crime scene. DNA testing of evidence that had been withheld from the defense for decades found the presence of an unidentified male’s DNA on the handle of the murder weapon. The testing found Payne’s DNA on the hilt of the knife, but not on the handle or any other location the killer’s hands would have been expected to touch while stabbing the victims more than 85 times.

The victims lived in an apartment across the hallway from Payne’s girlfriend. He has long maintained that he heard cries from the apartment and entered it to investigate. His lawyers said that evidence supports his testimony that he had touched the knife while trying to help the victims after the attack. Hearing police sirens, he then fled, fearing he would be considered a suspect.

For nearly two decades, prosecutors tried to execute Payne without any judicial review of his claim that he was ineligible for the death penalty because of intellectual disability. He was scheduled to be executed on December 3, 2020 but received a temporary reprieve from Governor Bill Lee based on coronavirus concerns. Responding to Payne’s case, the Tennessee legislature then amended the state’s post-conviction law to redress a flaw in the statute that had prevented death-row prisoners from presenting their intellectual disability claims to Tennessee’s courts. Payne became the first person to seek review under the new law, forcing prosecutors to finally address the issue. With a December 13 hearing date looming on Payne’s claim, the Shelby County District Attorney’s office conceded that he was ineligible for the death penalty.

Payne’s lawyers vowed to continue the fight to exonerate him. “Our proof that Pervis is intellectually disabled is unassailable, and his death sentence is unconstitutional,” said assistant federal defender Kelley Henry, Payne’s lead counsel. “The state did the right thing today by not continuing on with needless litigation. … We however will not stop until we have uncovered the proof which will exonerate Pervis and release him from prison.”

Julius Jones

Julius Jones also was convicted and sentenced to death in a racially charged case tried by a prosecutor’s office notorious for misconduct. Jones, who is Black, was prosecuted by Oklahoma County District Attorney “Cowboy Bob” Macy, who sent 54 people to death row during his 21 years as district attorney.

Macy was featured among the rogue’s gallery of America’s Top Five Deadliest Prosecutors in a June 2016 report by the Fair Punishment Project. At that time, courts had found prosecutorial misconduct in approximately one-third of Macy’s death penalty cases and had reversed nearly half of his death sentences. DPIC’s February 2021 special report, The Innocence Epidemic, found that the five death-row exonerations in Oklahoma County — all a product of official misconduct and/or false accusation — were the fourth most of any county in the U.S.

Jones was convicted and sentenced to death by a nearly all-white jury for the 1999 killing of Paul Howell, a prominent white businessman. In his commutation application, Jones wrote that “while being transferred from an Oklahoma City police car to an Edmond police car, an officer removed my handcuffs and said; ‘Run n****r. I dare you, run.’” In a June 2019 sworn affidavit, one of the jurors in Jones’ case said she overheard another juror say, during a break, “something to the effect of, ‘They just need to take this n****r and shoot him, and take him and bury him underneath the jail.”

Jones and his family have long said he was at home with them playing Monopoly at the time of the murder. However, his court-appointed trial lawyers failed to call any alibi witnesses, did not cross-examine his co-defendant, Christopher Jordan, and did not call Jones to testify on his own behalf. An eyewitness description of the shooter matched Jordan’s appearance, not Jones’. Jordan made a deal with prosecutors to testify against Jones and served 15 years.

At a clemency hearing before the Oklahoma Pardon and Parole Board, one of Jones’ lawyers presented the board with additional evidence: testimony from Roderick Wesley. Wesley said that while in prison, Jordan confessed that he had killed a man and that someone else was doing time on death row for his crime. Jones’ prosecutors asked the Board to disregard Wesley’s testimony because of his criminal record. Noting the irony, Jones’ lawyer pointed out that while the prosecution asserted that defense witnesses with felony convictions are not believable, it “at the same time has asked you to credit the testimony of its central witnesses, all of whom were convicted felons and informants themselves.”

The Oklahoma Pardon and Parole Board twice recommended that Jones’ sentence be reduced to life with the possibility of parole, based on evidence of Jones’ innocence. On September 13, and again on November 1, the board voted 3 – 1 to recommend clemency. On November 18, 2021, four hours before Jones’ execution was to be carried out, Governor Stitt commuted Jones’ sentence to life in prison without the possibility of parole. Stitt issued the commutation “on the condition that [Jones] shall never again be eligible to apply for, be considered for, or receive any additional commutation, pardon, or parole.”

Problematic Executions Top

Key Findings

- Ten of the eleven people executed in 2021 had evidence of a significant impairment

- Groundbreaking study found one of every seven executions involved a defendant who raised claims that the Supreme Court has said would require reversing their convictions or death sentences

- Texas performs execution with no media witnesses present

- Oklahoma schedules execution spree despite pending legal challenge to constitutionality of execution method

Though there were fewer executions in 2021 than in any year since 1988, the executions that were carried out highlighted serious systemic issues concerning who is executed, how they are executed, and the legal process leading up to executions.

As in past years, the eleven people executed in 2021 represented the most vulnerable or impaired prisoners, rather than the “worst of the worst.” All but one prisoner executed this year had evidence of one or more of the following significant impairments: serious mental illness (5); brain injury, developmental brain damage, or an IQ in the intellectually disabled range (8); chronic serious childhood trauma, neglect, and/or abuse (9). In addition, Quintin Jones was executed in Texas for a crime he committed at age 20, placing him in a category that neuroscience research has shown is materially indistinguishable in brain development and executive functioning from juvenile offenders who are exempt from execution.

Compounding doubt about the reliability of the judicial process to correct constitutional errors, a groundbreaking new study found that at least 228 people executed in the modern era — or more than one in every seven executions — were put to death despite raising legal claims that the Supreme Court has said would require reversing their convictions or death sentences. Some of these prisoners were “right too soon,” raising meritorious claims before the Supreme Court had ruled on the issue. However, most of the prisoners were executed after the Supreme Court had established the basis for relief, when the lower state and federal courts refused to enforce the Supreme Court’s rulings and the Court declined to intervene.

The execution procedure itself raised significant concerns in multiple states, as Texas performed an execution without media witnesses present and Oklahoma began an execution spree, despite ongoing legal challenges to its lethal-injection protocol and a botched execution. The year’s executions also presented questions of innocence, competency to be executed, and executions carried out against the wishes of the victim’s family. The first three executions of the year were the final executions carried out by the Trump administration. In addition to the aberrant practices discussed at greater length in the Federal Death Penalty section, the three prisoners executed in January — Lisa Montgomery, Corey Johnson, and Dustin Higgs — each presented case-specific reasons why their executions would be inappropriate.

Lisa Montgomery

Lisa Montgomery, the first woman executed by the federal government in 67 years, had been the victim of lifelong sexual and physical abuse, including being sexually trafficked by her mother. The conditions of her pre-execution incarceration, including being denied underclothing while being watched by male prisoner guards, recapitulated her prior sexual victimizations, exacerbating her already severe mental illness. As she decompensated under the stress of the death warrant, Montgomery’s lawyers filed motions for a competency hearing, arguing that her “deteriorating mental condition results in her inability rationally to understand she will be executed, why she will be executed, or even where she is. Under such circumstances, her execution would violate the Eighth Amendment.” Montgomery received four separate stays of execution from federal courts. The stays were meant to provide time for the courts to consider whether the federal government had violated federal law in the way it set her execution date and to hold a hearing on her mental competency. Two of these stays remained in effect at the time of Montgomery’s scheduled execution. But, without issuing any explanation of its reasoning, the U.S. Supreme Court lifted the stays hours after Montgomery’s execution had been scheduled to take place. After the original notice of execution warrant expired at midnight on January 12, the Bureau of Prisons issued a new notice scheduling her immediate execution on January 13 and proceeded to execute her at 1:31 a.m.

The following day, the federal government executed Corey Johnson without any judicial review of his claim that he was ineligible for the death penalty because of intellectual disability. He was the second intellectually disabled person put to death in the 2020 – 2021 federal execution spree to be denied an opportunity to present evidence of disability. Judge James A. Wynn, dissenting from the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit’s 8 – 7 denial of Johnson’s request for an evidentiary hearing, wrote, “Corey Johnson is an intellectually disabled death row inmate who is scheduled to be executed later today.” Newly available evidence, he wrote “convincingly demonstrates … that he is intellectually disabled under current diagnostic standards. But no court has ever considered such evidence. If Johnson’s death sentence is carried out today, the United States will execute an intellectually disabled person, which is unconstitutional.”

Dustin Higgs