Enduring Injustice: the Persistence of Racial Discrimination in the U.S. Death Penalty

DPIC Releases Report Placing Death Penalty in Historical Context as a “Descendant of Slavery, Lynching, and Segregation”

Death Penalty Must Be Part of Current Debate About Criminal Legal System Reforms

(Washington, D.C.) As social movements pressure policymakers to redress injustices in the criminal legal system and to institute reforms to make the process more fair and equitable, the Death Penalty Information Center (DPIC) today released, “Enduring Injustice: the Persistence of Racial Discrimination in the U.S. Death Penalty.” This report provides an in-depth look at the historical role that race has played in the death penalty and details the pervasive role racial discrimination continues to play in the administration of capital punishment today.

“The death penalty has been used to enforce racial hierarchies throughout United States history, beginning with the colonial period and continuing to this day,” said Ngozi Ndulue, DPIC’s Senior Director of Research and Special Projects and the report’s lead author. “Its discriminatory presence as the apex punishment in the American legal system legitimizes all other harsh and discriminatory punishments. That is why the death penalty must be part of any discussion of police reform, prosecutorial accountability, reversing mass incarceration, and the criminal legal system as a whole.” Ms. Ndulue previously served as the NAACP’s Senior Director of Criminal Justice Programs and as a capital appeals lawyer.

“Racial disparities are present at every stage of a capital case and get magnified as a case moves through the legal process,” said Robert Dunham, DPIC’s Executive Director and the report’s editor. “If you don’t understand the history — that the modern death penalty is the direct descendant of slavery, lynching, and Jim Crow-segregation — you won’t understand why. With the continuing police and white vigilante killings of Black citizens, it is even more important now to focus attention on the outsized role the death penalty plays as an agent and validator of racial discrimination. What is broken or intentionally discriminatory in the criminal legal system is visibly worse in death-penalty cases. Exposing how the system discriminates in capital cases can shine an important light on law enforcement and judicial practices in vital need of abolition, restructuring, or reform.”

The report documents the historic role of the U.S. death penalty as an instrument of social control. During slavery, capital punishment was a tool for controlling Black populations and curbing rebellions. After the Civil War, public officials promised legal executions as a means to discourage lynchings. As lynchings decreased in the early 20th century, executions began to take their place in circumstances that earlier would have drawn a lynch mob. Across the South, African-American men were condemned and executed for the alleged rape or attempted rape of white women or girls. No white man was ever executed for raping a Black woman or girl.

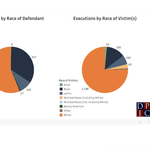

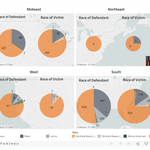

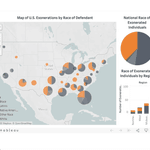

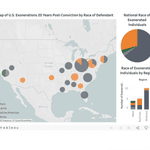

Racial bias persists today, as evidenced by cases with white victims being more likely to be investigated and capitally charged; systemic exclusion of jurors of color from service in death-penalty trials; and disproportionate imposition of death sentences against defendants of color. The report provides compelling evidence of racial bias in the modern death penalty, including:

- A 2015 meta-analysis of 30 studies showed that the killers of white people were more likely than the killers of Black people to face a capital prosecution.

- A study in North Carolina showed that qualified Black jurors were struck from juries at more than twice the rate of qualified white jurors. As of 2010, 20 percent of those on the state’s death row were sentenced to death by all-white juries.

- Since executions resumed in 1977, 295 African-Americans defendants have been executed for the murder of a white victim, while only 21 white defendants have been executed for the murder of an African-American victim.

- A 2014 mock jury study of more than 500 Californians found that white jurors were more likely to sentence poor Latinx defendants to death than poor white defendants.

- Exonerations of African Americans for murder convictions are 22 percent more likely to be linked to police misconduct.

The report highlights several pending death penalty cases where racial discrimination played a role in driving death sentences for Black defendants. For example:

- Abu-Ali Abdur’Rahman, Tennessee. In 2019, Davidson County District Attorney General Glenn Funk conceded that Abu-Ali Abdur’Rahman’s trial had been infected by overt racial bias. Abdur’Rahman had long argued that the prosecutor struck two Black potential jurors based on racial stereotypes. The trial court agreed to a reduced sentence, but the Tennessee Attorney General’s Office is currently appealing.

- Julius Jones, Oklahoma. Julius Jones, who has a strong innocence claim, was convicted and sentenced to death by a nearly all-white jury for killing a white businessman. His case was riddled with racial discrimination, including an officer using a racial slur during his arrest, prosecutors striking every Black potential juror but one, and a juror who used the n‑word to describe Jones. His petition for clemency is currently pending.

- Federal Death Penalty. Although the first set of executions scheduled by the federal government in 2020 have been strategically directed at white people, the federal death penalty has long been plagued by the same racial bias present in state death penalty systems. Thirty-four of the 57 people currently on federal death row are people of color, including 26 Black men. Some were convicted and condemned by all-white juries. In an action widely regarded as an assault on Native sovereignty, the sole Native American on federal death row was executed for an offense on tribal lands over the repeated objection of his tribe and Native American leaders across the country.

Lynchings v. Executions Interactive Visualization Top

Graphics Top