History Of The Death Penalty

Limiting the Death Penalty

Creation of International Human Rights Doctrines

In the aftermath of World War II, the United Nations General Assembly adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. This 1948 doctrine proclaimed a “right to life” in an absolute fashion, any limitations being only implicit. Knowing that international abolition of the death penalty was not yet a realistic goal in the years following the Universal Declaration, the United Nations shifted its focus to limiting the scope of the death penalty to protect juveniles, pregnant women, and the elderly.

During the 1950s and 1960s subsequent international human rights treaties were drafted, including the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, the European Convention on Human Rights, and the American Convention on Human Rights. These documents also provided for the right to life, but included the death penalty as an exception that must be accompanied by strict procedural safeguards. Despite this exception, many nations throughout Western Europe stopped using capital punishment, even if they did not, technically, abolish it. As a result, this de facto abolition became the norm in Western Europe by the 1980s. (Schabas, 1997)

Limitations within the United States

Despite growing European abolition, the U.S. retained the death penalty, but established limitations on capital punishment.

In 1977, the United States Supreme Court held in Coker v. Georgia (433 U.S. 584) that the death penalty is an unconstitutional punishment for the rape of an adult woman when the victim was not killed. Other limits to the death penalty followed in the next decade.

Mental Illness and Intellectual Disability

In 1986, the Supreme Court banned the execution of insane persons and required an adversarial process for determining mental competency in Ford v. Wainwright (477 U.S. 399). In Penry v. Lynaugh (492 U.S. 584 (1989)), the Court held that executing persons with “mental retardation” was not a violation of the Eighth Amendment. However, in 2002 in Atkins v. Virginia, (536 U.S. 304), the Court held that a national consensus had evolved against the execution of the “mentally retarded” and concluded that such a punishment violates the Eighth Amendment’s ban on cruel and unusual punishment.

Juveniles

In the late 1980s, the Supreme Court decided three cases regarding the constitutionality of executing juvenile offenders. In 1988, in Thompson v. Oklahoma (487 U.S. 815), four Justices held that the execution of offenders aged fifteen and younger at the time of their crimes was unconstitutional. The fifth vote was Justice O’Connor’s concurrence, which restricted Thompson only to states without a specific minimum age limit in their death penalty statute. The combined effect of the opinions by the four Justices and Justice O’Connor in Thompson is that no state without a minimum age in its death penalty statute can execute someone who was under sixteen at the time of the crime.

The following year, the Supreme Court held that the Eighth Amendment does not prohibit the death penalty for crimes committed at age sixteen or seventeen. (Stanford v. Kentucky, and Wilkins v. Missouri (collectively, 492 U.S. 361)). At present, 19 states with the death penalty bar the execution of anyone under 18 at the time of his or her crime.

In 1992, the United States ratified the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. Article 6(5) of this international human rights doctrine requires that the death penalty not be used on those who committed their crimes when they were below the age of 18. However, in doing so the U.S. reserved the right to execute juvenile offenders.

In March 2005, Roper v. Simmons, the United States Supreme Court declared the practice of executing defendants whose crimes were committed as juveniles unconstitutional.

Additional Death Penalty Issues

Race

Race became the focus of the criminal justice debate when the Supreme Court held in Batson v. Kentucky (476 U.S. 79 (1986)) that a prosecutor who strikes a disproportionate number of citizens of the same race in selecting a jury is required to rebut the inference of discrimination by showing neutral reasons for the strikes.

Race was again in the forefront when the Supreme Court decided the 1987 case, McCleskey v. Kemp (481 U.S. 279). McCleskey argued that there was racial discrimination in the application of Georgia’s death penalty, by presenting a statistical analysis showing a pattern of racial disparities in death sentences, based on the race of the victim. The Supreme Court held, however, that racial disparities would not be recognized as a constitutional violation of “equal protection of the law” unless intentional racial discrimination against the defendant could be shown.

Innocence

The Supreme Court addressed the constitutionality of executing someone who claimed actual innocence in Herrera v. Collins (506 U.S. 390 (1993)). Although the Court left open the possibility that the Constitution bars the execution of someone who conclusively demonstrates that he or she is actually innocent, the Court noted that such cases would be very rare. The Court held that, in the absence of other constitutional violations, new evidence of innocence is no reason for federal courts to order a new trial. The Court also held that an innocent person could seek to prevent his execution through the clemency process, which, historically, has been “the ‘fail safe’ in our justice system.” Herrera was not granted clemency, and was executed in 1993.

Since Herrera, concern regarding the possibility of executing the innocent has grown. Currently, 201 people have been released from death row because of innocence since 1973. In November, 1998 Northwestern University held the first-ever National Conference on Wrongful Convictions and the Death Penalty, in Chicago, Illinois. The Conference, which drew nationwide attention, brought together 30 of these wrongfully convicted people who were exonerated and released from death row. Many of these cases were discovered not as the result of the justice system, but instead as the result of new scientific techniques, investigations by journalism students, and the work of volunteer attorneys. These resources are not available to the typical death row inmate.

In January 2000, after Illinois had released 13 innocent people from death row in the same time that it had executed 12 people, Illinois Governor George Ryan declared a moratorium on executions and appointed a blue-ribbon Commission on Capital Punishment to study the issue.

Public Support

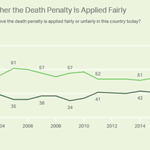

Support for the death penalty has fluctuated over the past century. According to Gallup surveys, in 1936 61% of Americans favored the death penalty for persons convicted of murder. Support reached an all-time low of 42% in 1966. Throughout the 70s and 80s, the percentage of Americans in favor of the death penalty increased steadily, culminating in an 80% approval rating in 1994. By 2018, this number had dropped dramatically with Gallup measuring overall support for capital punishment at 56%. The same year, 49% of Americans said they believed the death penalty was “applied fairly”, the lowest Gallup has ever recorded since it first included the question in its crime poll in 2000. The percentage of U.S. adults who said they believe the death penalty is unfairly applied rose to 45%, the highest since Gallup began asking the question, and the four-percentage-point difference between the two responses was the smallest in the history of Gallup’s polling. The poll also found that the percentage of Americans saying that the death penalty is imposed too often continued to rise and the percentage saying it is not imposed enough continued to decline. 57% of U.S. adults said the death penalty was imposed either “too often” (29%) or “about the right amount” (28%). By contrast, in 2010, 18% said the death penalty was imposed too often. 37% said the death penalty was not imposed enough, down 16 percentage points from the 53% level who in 2005 said it was not imposed enough. (See also, DPI’s report, Sentencing for Life: American’s Embrace Alternatives to the Death Penalty)

Religion

In the 1970s, the National Association of Evangelicals (NAE), representing more then 10 million conservative Christians and 47 denominations, and the Moral Majority, were among the Christian groups supporting the death penalty. NAE’s successor, the Christian Coalition, also supports the death penalty. Today, Fundamentalist and Pentecostal churches support the death penalty, typically on biblical grounds, specifically citing the Old Testament. (Bedau, 1997). The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints regards the question as a matter to be decided solely by the process of civil law, and thus neither promotes nor opposes capital punishment.

Although traditionally also a supporter of capital punishment, the Roman Catholic Church now oppose the death penalty. In addition, most Protestant denominations, including Baptists, Episcopalians, Lutherans, Methodists, Presbyterians, and the United Church of Christ, oppose the death penalty. During the 1960s, religious activists worked to abolish the death penalty, and continue to do so today.

In recent years, religious organizations around the nation have issued statements opposing the death penalty.

Women

Women have, historically, not been subject to the death penalty at the same rates as men. From the first woman executed in the U.S., Jane Champion, who was hanged in James City, Virginia in 1632, to the present, women have constituted only about 3% of U.S. executions. In fact, only 18 women have been executed in the post-Gregg era. (Shea, 2004, with updates by DPIC).