History Of The Death Penalty

Recent Developments in Capital Punishment

Federal Death Penalty

In 1988, President Reagan signed the Anti-Drug Abuse Act. This legislation included a provision, sometimes referred to as the “drug kingpin” death penalty, which created an enforceable federal death penalty for murders committed by those involved in certain drug trafficking activities. The death penalty provisions were added to the “continuing criminal enterprise” statute first enacted in 1984, 21 U.S.C. SS 848. The drug trafficking “enterprise” can consist of as few as five individuals, and even a low-ranking “foot soldier” in the organization can be charged with the death penalty if involved in a killing.

In 1994, President Clinton signed the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act that expanded the federal death penalty to some 60 crimes, 3 of which do not involve murder. The exceptions are espionage, treason, and drug trafficking in large amounts.

Two years later, in response to the Oklahoma City Bombing, President Clinton signed the Anti-Terrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996 (AEDPA). The Act, which affects both state and federal prisoners, restricts review in federal courts by establishing tighter filing deadlines, limiting the opportunity for evidentiary hearings, and, absent narrow circumstances, allows only a single habeas corpus filing in federal court. Proponents of the death penalty argue that streamlining the process will cost less, lessen lengthy appeals, and achieve finality for the victims and their families. Opponents fear that quicker, more limited federal review will increase the risk of executing innocent defendants (Larkin, 2022).

The first federal execution following the reinstatement of the federal death penalty in 1988 took place in June of 2001, with the execution of Timothy McVeigh. Two additional federal executions, another in June 2001 and one in March 2003, occurred during President George W. Bush’s administration. Thirteen federal executions were carried out in a six-month period between July 2020 and January 2021 during President Donald Trump’s administration. In total, sixteen executions by lethal injection have been carried out by the federal government since the reinstatement of the federal death penalty.

International Abolition

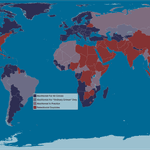

In the 1980s the international abolition movement gained momentum and new treaties supporting abolition were drafted and ratified by many countries. Protocol No. 6 to the European Convention on Human Rights and its successors, the Protocol to the American Convention on Human Rights to Abolish the Death Penalty, and the United Nation’s Second Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, aiming at the abolition of the death penalty, were created with the goal of making abolition of the death penalty an international norm.

Today, the Council of Europe requires new members to undertake and ratify Protocol No. 6. This has, in effect, led to the abolition of the death penalty in Eastern Europe, where only Belarus retains the death penalty. For example, the Ukraine, formerly one of the world’s leaders in executions, has now halted the death penalty and has been admitted to the Council. South Africa’s parliament voted to formally abolish the death penalty in 1995, after earlier being declared unconstitutional by the Constitutional Court. In addition, Russian President Boris Yeltsin signed a decree commuting the death sentences of all the prisoners in Russia in June 1999 (Amnesty International and Associated Press, 1999). Between 2000 and 2022, 38 additional countries abolished the death penalty for all crimes, 6 more abolished the death penalty for ordinary crimes, and 1 abolished a mandatory death penalty for murder.

In April 1999, the United Nations Human Rights Commission passed the Resolution Supporting Worldwide Moratorium on Executions. The Resolution calls on countries which have not abolished the death penalty to restrict its use of the death penalty, including not imposing it on juvenile offenders and limiting the number of offenses punishable by death. Ten countries, including the United States, China, Pakistan, Rwanda and Sudan voted against the resolution. In October 2021, the UNHRC adopted the resolution once again, with 29 member states in favor of it, 12 voting against it, and 5 abstaining from the vote.

The United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) first adopted a resolution for an international execution moratorium in December 2007. As of December 2022, the UNGA again adopted a resolution, co-sponsored by 125 UN members states, calling for a global moratorium on the use of the death penalty. Moratorium resolutions have thereafter been introduced in each UNGA session since 2007, where the initial resolution had 104 supporting members. The United States has voted no on all resolutions.

Lethal Injection

Lethal injection has been the most common method of execution in the modern era of capital punishment in the United States. Between the resumption of executions in 1977 and August 31, 2018, 1,306 executions (nearly 90%) used lethal injection. When states first turned to using drugs in executions, many did so in the belief that lethal injection would be more humane than the more visibly gruesome methods it replaced: hanging, electrocution, gas, and firing squad. Other states adopted lethal injection to avoid legal challenges to the constitutionality of their prior methods.

Despite states’ purported goal of ensuring more humane executions, scholars have estimated that more than 7% of lethal-injection executions in the U.S. through 2010 were botched. Beginning in 2011, as states have experimented with new execution drugs, reports of problematic executions have noticeably increased. At the same time, states have enacted laws or adopted constitutional amendments that prevent the public from obtaining information about lethal injection drugs and suppliers. (For more information, see DPIC’s report Behind the Curtain: Secrecy and the Death Penalty in the United States.)

Legislative bodies in at least 13 states have enacted secrecy statutes related to capital punishment that conceal details about their execution process and protocol. In 2015, the American Bar Association passed a resolution urging “each jurisdiction that imposes capital punishment to ensure that it has execution protocols that are subject to public review and commentary and include all major details regarding the procedures to be followed, the qualifications of the execution team members, and the drugs to be used.” Many pharmaceutical developers, including Pfizer and Merck, have publicly opposed the use of their products in execution protocols, emphasizing the goal of their products is to improve and save the lives of their patients.

As access to commonly used execution-drugs has become increasingly restricted, states have implemented alternative drug protocols and combinations. Midazolam, a benzodiazepine (sedative) is the first drug used in many three-drug execution protocols. This first drug is intended to place the prisoner in coma-like state, unable to outwardly express the pain caused by the second drug, a paralytic, or the third drug, which causes cardiac arrest. In more than 60% (7 of 11) of the midazolam executions in 2017, eyewitnesses reported prisoner reactions ranging from labored breathing to gasping, heaving, writhing, and clenching fists, that suggest they were experiencing pain.