Human Rights

Race, Human Rights, and the U.S. Death Penalty

From enslavement to lynching, race massacres, the genocide against indigenous peoples, Jim Crow segregation, and immigrant exclusion policies, the United States has a long history of human rights abuses arising out of racial violence and discrimination.

Following the ratification of the post-Civil War amendments to the U.S. Constitution that ended chattel slavery and guaranteed equal protection of the law to all Americans, and the landmark Reconstruction Era Civil Rights Act, governmental acts of racial discrimination became unconstitutional and unlawful in this country. While enshrined as the law of the land, those rights are often violated and those violations are often not redressed by the courts. Whether deemed a violation of domestic law or not, those governmental acts of racial discrimination — and toleration of racial discrimination by non-enforcement of prohibitions against it — may violate international human rights law.

International Context on Race and Human Rights

The International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination was adopted in 1965 and ratified, with reservations, by the United States in 1994. Article 2 sweepingly “condemn[s] racial discrimination” and commits parties to the treaty to “undertake to pursue by all appropriate means and without delay a policy of eliminating racial discrimination in all its forms.” Article 2, Section 1(a) makes clear that the obligations of the treaty extend beyond federal governments, committing countries “to engage in no act or practice of racial discrimination … and to ensure that all public authorities and public institutions, national and local, shall act in conformity with this obligation.”

Article 6 of the Convention requires countries to “assure to everyone within their jurisdiction effective protection and remedies, through the competent national tribunals and other State institutions, against any acts of racial discrimination.” The failure of Congress to provide effective remedies and the refusal of federal courts to enforce them are themselves violations of international human rights norms, separate and apart from the initial violation by state or local government actors.

Although the United States signed ICERD in 1966, it was not ratified by the Senate until October 1994. The Senate declared the treaty to be “not self-executing,” meaning that its provisions would be unenforceable in U.S. courts unless Congress separately enacted legislation making it part of U.S. domestic law. Congress has not done so, nor has it enacted legislation that would permit individuals who believed their human rights under ICERD had been violated to bring suit in U.S. courts. It also refused to submit disputes under ICERD to the jurisdiction of the International Court of Justice without “the specific consent of the United States … in each case.”

According to the American Bar Association Section on Civil Rights and Social Justice, these actions “nullify the treaty’s effect” and demonstrate a “hollow” and “watered-down commitment … toward ICERD’s goal of eliminating global racial discrimination.”

In recent years, international human rights bodies have criticized the United States for endemic racial discrimination throughout its criminal legal system. Following the extrajudicial killing of George Floyd by Minneapolis police, and during the subsequent Black Lives Matter protests, the United Nations Human Rights Council called for an urgent debate in June 2020. In that session, the council discussed systemic racism and violations of international human rights law committed by law enforcement officials against Africans and people of African descent around the world, and proposed a “transformative agenda” to “end impunity for human rights violations by law enforcement officials and … ensure that the voices of people of African descent and those who stand up against racism are heard and that their concerns are acted upon.” The session concluded with a resolution calling upon the UN Office of the High Commissioner on Human Rights to conduct a thorough report on the matter.

In 2021, the “groundbreaking” racial justice report was released and provided 20 actionable recommendations. Unsatisfied with the progress since, the Office of the High Commissioner released a subsequent report in 2022 identifying “piecemeal progress in combating systemic racism.” The racial justice report specifically noted “the disproportionate impact of the death penalty, punitive drug policies, arrests, overrepresentation in prisons and other aspects of the criminal justice system on people of African descent in different countries” and quoted Amnesty International’s 2021 Global Report on Death Sentences and Executions that charged that “many cases of those who faced the death penalty [in the United States] in 2021 were also affected by concerns of racial discrimination and bias.”

The 2020 United Nations Universal Periodic Review of the United States’ human rights record includes generalized criticism from several UN bodies regarding the discriminatory nature of the U.S. capital punishment system. The Working Group of Experts on People of African Descent, which had previously expressed concern about the existence of capital punishment in 2016, noted that those of African descent were disproportionally affected, citing the fact that they represented over 40% of the U.S. death row population. The Working Group on Arbitrary Detention noted that “African Americans were more likely to be sentenced to longer terms of imprisonment” and expressed concern “about the existence of racial disparities at all stages of the criminal justice system.”

Evidence of Race Discrimination in the U.S. Death Penalty

Everywhere in the world in which the death penalty exists, it is applied disproportionately against racially, religiously, ethnically, and politically disfavored groups. The United States is no exception to that worldwide rule.

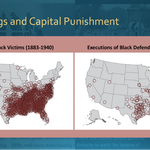

The United States death penalty is often referred to as a descendent of the American historical practices of enslavement, lynching, and Jim Crow segregation. Studies have found that states with a greater history of lynchings also tend to have more modern death sentences, and that the link is even stronger between lynchings and death sentences imposed upon Black defendants.[1] A 2022 study documented the “deep historical and contemporary connection [between the death penalty and] white racial hostility toward blacks.”[2] It found that the same “racial resentment of blacks [that] drives support for the death penalty at the individual level” operates at the state level and that “states with higher aggregate levels of racial resentment impose more death sentences,” particularly against African Americans. From slavery to lynching to segregation to the death penalty and mass incarceration, the researchers wrote, “[r]acial attitudes that historically led to discrimination and racial subjugation reproduce themselves within the white population through the institutions and political cultures of a given area.”

Studies show that racial discrimination operates and compounds itself at each stage of a potentially capital case, from policing practices, to charging decisions, to plea negotiations, and on through the process of trial, sentencing, appeal, and execution.[3] A review of a dataset of 2,328 Georgia first-degree murder convictions that produced 1,317 death eligible cases found that two sets of factors operated in combination to determine who would be executed: “victim race and gender, and a set of case-specific features that are often correlated with race.”[4] Indeed, Georgia data showed that “racial disparities persist and … are magnified during the appellate and clemency processes,” with the net result that “the overall execution rate is a staggering seventeen times greater for defendants convicted of killing a white victim.”[5]

Other landmark studies have documented similar phenomena: after rating cases based upon the perceived severity of a murder, African Americans were more likely to be sentenced to death than white defendants irrespective of the race of the victim and the severity of the murder, and a death sentence was more likely to be imposed in a case involving one or more white victims, irrespective of the race of the defendant and the severity of the murder. The combination of race of victim and race of defendant most likely to produce a death verdict at all levels of severity was a Black defendant and a white victim.

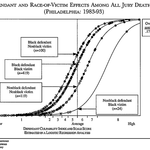

A study of the death penalty in Philadelphia,[6] which in 2001 had 113 African Americans on death row — 25 more than any other county in the U.S.[7] — found that the odds that a capital trial would result in a death sentence were 3.1 times greater if the defendant was Black; and those odds became 9.3 times greater if the case advanced to a capital penalty phase; and 29.0 times greater if a jury found both aggravating and mitigating circumstances to be present and had to make the discretionary choice between life or death.

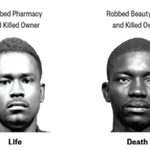

To explore the impact of racial bias — overt or implicit — on capital sentencing, other researchers examined whether the defendant’s appearance affected the likelihood of a death sentence.[8] They rated African American capital defendants based upon the degree to which they had prototypically African facial features (i.e., darker skin, broader nose, and thicker lips) and examined sentencing outcomes based upon the race of the victim. They found that a Black defendant’s appearance had no statistically significant difference in sentencing outcomes if the victim also was Black. But in cases in which the victim was white, a Black defendant with archetypical African features was twice as likely to be sentenced to death as a Black defendant with lighter skin, a narrower nose, and thinner lips.

The racist underpinnings of the U.S. death penalty — and its emergence as a successor to extrajudicial lynchings — can be seen most clearly in the historical application of the death penalty for allegations of rape. Between 1930 and 1972, 455 people in the United States were executed for rape. 405 (89.1%) of those executed were Black. 443 of the executions for rape (97.3%) occurred in the states of the former Confederacy. No white man has ever been executed in the U.S. for the rape of a Black woman or child in which the victim was not killed. For most of the 20th century, Virginia permitted the death penalty for rape, attempted rape, and armed robbery that did not result in death. 73 Black men and boys were executed on charges they had committed non-lethal acts. No white person was executed for an offense that did not result in death.

In the “modern era” — since states began re-enacting death penalty laws after the Supreme Court struck down existing death penalty statutes in 1972 — executions have been limited to cases in which a victim was killed. That has eliminated the huge racial bias present in death penalty cases for non-lethal offenses. However, significant race-of defendant and race-of victim bias remains. Executions disproportionately involve white victims, suggesting an inappropriate race-based conception of what constitutes the “worst of the worst” killings. And among the most vulnerable of defendants — juveniles, late adolescents, the intellectually disabled, and those who are innocent and have been wrongfully convicted and sentenced to death — significant bias permeates the death penalty system.

More than two thirds (30 of 44) of the known intellectually disabled prisoners who were executed before the Supreme Court banned the practice in Atkins v. Virginia in 2002 were people of color. More than 60% (27 of 44) were Black. Over the next twenty years, U.S. states executed at least 29 more prisoners who most likely were intellectually disabled. More than three-quarters (22, 75.9%) were people of color and 62.1% (18 of 29) were Black. As of December 2022, at least 142 condemned prisoners had their death sentences overturned under Atkins: More than 4 in 5 (118, 83.1%) were people of color and more than two-thirds (96, 67.6%) were Black.

Similarly, nearly two-thirds (65.2%) of the 235 death sentences imposed on juvenile offenders (under age 18) in the United States in the modern era before the Supreme Court struck down that practice in Roper v. Simmons in 2005 were people of color.[9] More than half (52.0%) were Black. 64.7% of the 1,319 death sentences imposed on late adolescent offenders (between ages 18 and 21) in the U.S. in the modern era have been directed at people of color, with more than half imposed on Black adolescents (51.2%).[10] Noting that “Black youth are punished more harshly than Whites” and that “it is clear death as a penalty is not applied equally and fairly among members of the late adolescent class,” the American Psychological Association in August 2022 adopted a resolution calling for an end to the death penalty for individuals aged 18 – 20.

The National Registry of Exonerations has documented that Black defendants charged with murder are much more vulnerable to wrongful convictions than are their white counterparts. In its 2022 report, Race and Wrongful Convictions in the United States, the Registry found that Black people are about 7½ times more likely to be wrongfully convicted of murder in the U.S. than are whites, and about 80% more likely to be innocent than others convicted of murder. The already disproportionate risk of wrongful conviction, the Registry found, was even worse if the murder victim in a case was white.

Not surprisingly, death-row exonerations highlight the enhanced risk of wrongful conviction that innocent defendants of color face in their capital trials. Nearly two-thirds of wrongfully convicted death-row prisoners who have subsequently been exonerated are individuals of color and more than half are Black. As of March 2023, DPI had documented 191 death-row exonerations since 1973: one exoneration for every 8.2 executions in the United States in the past half century. DPI’s exoneration data shows that exonerees of color, and particularly those who are Black, are more likely to be victims of official misconduct and false accusation, more likely to be wrongfully convicted and condemned, and more likely to spend longer periods facing execution or under the continuing shadow of their wrongful conviction than white death-row exonerees.

Reframing the Death Penalty as a Human Rights Issue Rather than a Legitimate Tool of Public Safety

In most of the democratic nations of the world, the death penalty is viewed as a human rights issue. And when the United States looks outward at the death penalty policies and practices of autocratic regimes like Iran, Saudi Arabia, China, North Korea, and Belarus, it, too, tends to frame the issue in terms of human rights. But Americans rarely turn the human rights lens inward towards this nation’s death penalty practices. Instead, internally, the death penalty tends to be discussed as a legitimate criminal legal policy option in promoting and protecting public safety.

However, that is beginning to change as historians, academics, and policy advocates increasingly address the historical use of enslavement and punishment as instruments of social control in the United States and the continuing role the death penalty plays in legitimizing other policies of mass incarceration.

In a 2015 interview with The Marshall Project, Equal Justice Initiative founder and executive director Bryan Stevenson observed that the United States has “never committed itself to a conversation about the legacy of slavery. … Very few people in this country have any awareness of just how expansive and how debilitating and destructive America’s history of slavery is.”

“The whole narrative of white supremacy was created during the era of slavery. It was a necessary theory to make white Christian people feel comfortable with their ownership of other human beings,” Stevenson said. “And we created a narrative of racial difference in this country to sustain slavery, and even people who didn’t own slaves bought into that narrative, including people in the North. … We created a narrative of racial difference to maintain slavery. And our 13th amendment never dealt with that narrative. It didn’t talk about white supremacy. The Emancipation Proclamation doesn’t discuss the ideology of white supremacy or the narrative of racial difference. So I don’t believe slavery ended in 1865, I believe it just evolved. It turned into decades of racial hierarchy that was violently enforced — from the end of reconstruction until WWII — through acts of racial terror.”

During the 2018 dedication of EJI’s lynching memorial, the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, Stevenson called capital punishment “the stepchild of lynching. … It was disproportionately used against people of color; it still continues to be shaped primarily by race,” he said.

Stevenson argues that “we’ve used the death penalty to sustain racial hierarchy by making it primarily a tool to reinforce the victimization of white people. The greatest racial disparity of the death penalty is the way in which the death penalty is largely reserved for cases where the victims are white. … And that’s true throughout this country. We’ve used it particularly aggressively when minority defendants are accused of killing white people. And history is replete with defendants being described with the n‑word, cases just saturated with racial bigotry, and the courts have largely tolerated that.” He says that the occasional pursuit of the death penalty for hate crimes targeting Black victims does not legitimize the death penalty. “We can’t be distracted by thinking that if they execute one person who committed mass violence that’s some sign of progress. That’s a sign of tactical misdirection to preserve a system that is inherently corrupted by a narrative of racial difference.”

In a 2023 Discussions With DPI podcast interview, Georgetown University Racial Justice Institute Executive Director Diann Rust-Tierney observed that “for a long time, the death penalty has been misclassified … as if it was a normal public safety tool, notwithstanding the fact that there is no relationship between safety and the death penalty, that we don’t see reduction in the crime or murder in places that use the death penalty.” Rust-Tierney describes the suggestion that the death penalty is a tool of public safety as “fiction.” Rather, she says, “the death penalty really [is] part of something much more terrible. It is part of the racial caste system in the United States.”

“[F]rom its very beginning in history, from the very first time that Africans were brought to the United States to work, it was part of a legal and social system designed to keep various races in their place and to reinforce the institution of slavery,” Rust-Tierney says. “And the most important thing that the death penalty does, and did then, is to tell us the value of different lives. In other words, it places a different value on the life of a victim, depending upon their race, and it places a different value on the life of the defendant based on their race. That’s something we’ve seen historically, and so it was important to understand that the death penalty is not a tool of public safety, but it is in fact, a tool of racial and social oppression.”

Rust-Tierney frames the discussion of capital punishment in the U.S. and worldwide as part of “a global struggle for human rights, a global struggle for democracy.” She notes that the most aggressive death penalty states in the U.S. are engaging in a broad range of anti-democratic practices, making their execution practices state secrets, attempting to bar African Americans from jury service through regulations and rules that limit who can serve on a jury or through the discriminatory use of jury strikes, attempting to overturn the results of local elections in which reform prosecutors have said that they don’t intend to seek the death penalty or are going to seek the death penalty more sparingly, and trying to oppress a significant segment of their population through voter suppression. “The reality,” she says, “is that the death penalty is a tool of oppression. Autocrats and anti-democratic people and dictators use death as punishment, and they wield it where they will, and how they will …. [T]he death penalty is a tool of power.”

Rust-Tierney says “it’s time to stand on the side of either democracy and self determination and human rights on this side or on the side of autocracy and oppression and dictators. And in that stark contrast, you have to oppose the death penalty.”

Resources

DPI Webinars: Webinar on Race and the U.S. Death Penalty ;

German Embassy Panel on Human Rights & the U.S. Death Penalty, Diann Rust Tierney speaks at 54min

DPI Report: Enduring Injustice

DPI Webpage: Race Page

Human Rights Council holds an urgent debate on current racially inspired human rights violations, systemic racism, police brutality and violence against peaceful protests

Agenda towards transformative change for racial justice and equality

International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination

IACHR Precautionary Measure on Julius Jones

2020 Universal Period Review of United States Human Rights Record

Cornell Center on the Death Penalty Worldwide: Discrimination Page

Cornell Center on the Death Penalty Worldwide: Arbitrariness Page

Cornell Center on the Death Penalty Worldwide: Due Process Page

Footnotes:

[1] David Jacobs, Jason T. Carmichael, and Stephanie L. Kent, Vigilantism, Current Racial Threat, and Death Sentences, American Sociological Review 656 – 77, Vol. 70 (Aug. 2005).

[2] Frank R. Baumgartner, Christian Caron, and Scott Duxbury, Racial Resentment and the Death Penalty, The Journal of Race, Ethnicity, and Politics 1 – 19 (2022).

[3] Jeffrey Fagan, Garth Davies, and Raymond Paternoster, Getting to Death: Race and the Paths of Capital Cases After Furman, 107 Cornell Law Review 1565 – 1620 (2022); Scott Phillips and Justin F. Marceau, Whom the State Kills, 55 Harvard Civil Rights-Civil Liberties Law Review 585 – 656, Issue 2 (Summer 2020).

[4] Fagan et al., at 1565.

[5] Phillips and Marceau, at 603.

[6] David C. Baldus, George Woodworth, David Zuckerman, and Neil Alan Weiner, Racial Discrimination and the Death Penalty in the Post-Furman Era: An Empirical and Legal Overview with Recent Findings from Philadelphia, 83 Cornell Law Review 1638 – 1770 (1998).

[7] Robert Dunham, Racial composition of death row in the seventy most populous counties in states with the death penalty, July 16, 2001, document on file with the Death Penalty Information Center.

[8] Jennifer L. Eberhardt, P G. Davies, Valerie J. Purdie-Vaughns, and Sheri Lynn Johnson, Looking Deathworthy: Perceived Stereotypicality of Black Defendants Predicts Capital-Sentencing Outcomes, Psychological Science 383 – 86, Vol. 17, No. 5 (2006).

[9] For whom race is known. 235 people were sentenced to death for crimes committed before they turned age 18. 115 were Black; 77 were white; 26 were Hispanic; 3 were of other races; and race data was missing for 14.

[10] Again, for whom race is known. 1,319 death sentences were imposed on late adolescent offenders. 640 were Black; 442 were white; 139 were Hispanic; 30 were of other races; and race data was missing for 68 cases.