Sentencing Alternatives

Restorative Justice

Overview

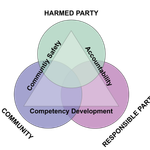

Restorative justice is a set of principles and practices that respond to criminal behavior with goals of restitution and resolution, rather than focusing on retribution. These practices work to address the dehumanization that many people experience in the traditional criminal legal system. Rather than viewing criminal behavior as a violation of the law, restorative justice considers this behavior to be a violation of community and interpersonal relationships. Restorative justice practices intend to look at the impact of each crime and determine what is necessary to mitigate the harm caused, while still holding the person accountable for his actions. Unlike the traditional criminal legal system, restorative justice also seeks out to addresses the causes of criminal behavior, as well as how to prevent recidivism. As a diversion practice, restorative justice can lessen direct involvement in the criminal legal system. Success is not measured by punishment, but rather the reparation of harm.

The process of restorative justice includes those most directly impacted by the crime at hand. In practice, victims, defendants, community members, and justice professionals come together to discuss the harms brought about by criminal behavior. Rather than focusing on the actions of the person who caused harm, restorative justice centers the conversation around those who have been harmed and what they have experienced. For many victims, this empowerment is not found in the traditional criminal legal system. Community members also have stake in the conversation, helping to hold people who commit crimes accountable and providing support to the parties involved. Justice professionals act as facilitators, focusing on community development instead of surveillance.

Restorative justice has been used in a limited number of death penalty cases with varied levels of success. While most states have implemented restorative justice processes for low-level nonviolent and violent crimes, there have only been a few jurisdictions willing to try restorative justice with homicides and capital cases. Some defense counsel working in the traditional legal system fear that the use of restorative justice in these cases may violate a defendant’s Constitutional right against self-incrimination. Since restorative justice is founded on the principle of accountability, it is almost inevitable that a defendant will make an admission of his own guilt during the restorative justice process. This can become problematic if an individual has not been formally sentenced, as there are currently no processes to exclude these potentially incriminating statements. Discussions in the restorative justice process often include information about what led someone to act in a criminal manner, and this may involve admissions of other criminal behavior. Whether or not the crime in question is resolved, there are concerns about statements made during restorative proceedings that could be used against the defendant in separate criminal proceedings (Lanni 2021). Attorneys for those facing the death penalty often cite this self-incrimination concern because of the lengthy appeals process that restorative justice may even further complicate. For those working in the restorative justice space, the severity of the crime at hand should not be the factor that stops restorative justice from proceeding. Senior Fellow sujatha baliga, who works with Impact Justice, an organization focused on criminal justice reform, believes that “with proper training… we can use restorative justice early on in any crime.”

Restorative Justice Pillars

Focuses on harm caused by crime.

Restorative justice views crime as harm done to people and communities and focuses on repairing harm in both concrete and symbolic ways. The victim-oriented nature of restorative justice allows for victims’ needs to be considered even when the identity of the person who committed the crime is unknown. By focusing on harm, restorative justice also aims to address the harm of the larger community, looking to address the root causes of the criminal behavior.

Wrongs or harms result in obligations.

Since restorative justice focuses on harm, people who commit crimes must begin to understand the consequences of the harm they caused. They must also take responsibility and try to correct harms, both concretely and symbolically.

Promote engagement and participation.

All involved stakeholders need to know about each other and be involved in defining what justice looks like in their case. This communication can happen in conferences, where stories and experiences are shared and a consensus about the next steps is reached, or through indirect exchanges, like victim-impact panels.

“Restorative justice requires, at minimum, that we address victims’ harms and needs, hold offenders accountable to put right those harms, and involve victims, offenders and communities in this process.”

Approaches to Restorative Justice

Family Group Conferences

Family group conferences (FGCs) are structured conversations with a facilitator, that provide an opportunity for key individuals impacted by a specific crime — the victim(s), the person(s) who caused the harm, and their respective family and friends — to openly discuss the impact of the given harm and determine appropriate measures of accountability for the responsible party. FGCs started in New Zealand and worked to include indigenous Māori values in addressing wrongdoings. Falling under the theory of reintegrative shaming, group conferencing advocates “argue that people are generally deterred from committing crimes by two informal types of social control: conscience and fear of social disapproval” (Braithwaite 1989).

Victim-Impact Panels

Victim-impact panels are dedicated to providing crime victims with the opportunity to share with the person who caused harm how their criminal behavior impacted them. These panels do not always require the participation of the victims; as surrogate victims, friends, and family with similar experiences may speak on the victim’s behalf. Whether the victim is present or not, these panels help the person who committed the crime to individualize the people or person they harmed as well as demonstrating the impact of their behavior on the victim and community. Victim-impact panels are gaining in popularity and have become a sentence alternative for a variety of violent and non-violent crimes, including property crimes and domestic violence.

Mediation

Victim-defendant mediation offers victims the chance to talk to the person who caused them harm in a safe environment focused on discussion, negotiation, and resolution. These meetings have two main goals: (1) hold the person directly accountable for their actions, learn how their actions impacted others, and determine how to repair the harm(s) they caused; and (2) provide victims with a sense of empowerment. Nearly all victim-defendant mediation groups believe “the purpose of victim-defendant mediation is not to determine guilty (generally, guilt has already been determined in another forum), rather it is to teach the [defendant how] to accept responsibility and repair harm.” Through continuous, open dialogue, and the assistance of a facilitator, participants are provided with an opportunity to express their feelings and “develop mutually acceptable restitution plans that address the harm caused by the crime” (DOJ 2010).

Circle Sentencing

Circle sentencing, often referred to as peacemaking circles, stem from the traditional practices of Indigenous Americans and Canadian Aboriginals. This is a community-guided process designed to address criminality and delinquency. Victims, defendants, family, friends of both parties, social and justice personnel, as well as community members make up the ‘circle.’ Through conversation, each party details how the events impacted them and attempts to understand why the crime in question occurred. Circle members work together to “identify the steps needed to assist in the healing [of] all affected parties and prevent future crimes.” Circle sentencing varies for every community, as it is often designed to work cohesively with local needs and culture. However, most circle sentencing groups are facilitated by a trained community member.

Community Reparative Boards

Community reparative boards are made up of a few specially trained citizens who conduct in-person, face-to-face sessions with defendants facing court-ordered participation. Board members discuss a penalty agreement with the person who has committed the crime, supervise his compliance, and provide the courts with these compliance records. While most restorative justice models rely on the participation of the crime victim, community reparative boards may be better suited to take input from community members. Because victims are not directly involved in these processes and it is often a court-ordered practice, some suggest that community reparative boards have less of a reparative effect than other restorative justice models.

Recent Studies and Research

- Kennedy, J. L. D., Tuliao, A. P., Flower, K. N., Tibbs, J. J., & McChargue, D. E. (2019). Long-Term Effectiveness of a Brief Restorative Justice Intervention. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 63(1), 3 – 17. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624X18779202

- Levinson, O. Reconciling Ideals: Restorative Justice as an Alternative to Sentencing Enhancements for Hate Crimes, Minnesota Law Review, 2020 – 2021.

- Lloyd, A., Borrill, J. Examining the Effectiveness of Restorative Justice in Reducing Victims’ Post-Traumatic Stress. Psychol. Inj. and Law 13, 77 – 89 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12207-019 – 09363‑9

- Sliva, SM, Plassmeyer, M. Effects of restorative justice pre-file diversion legislation on juvenile filing rates: An interrupted time-series analysis. Criminal Public Policy. 2021; 20: 19– 40. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745 – 9133.12518

- Lodi E, Perrella L, Lepri GL, Scarpa ML, Patrizi P. Use of Restorative Justice and Restorative Practices at School: A Systematic Literature Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(1):96. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010096

- Alfred Allan, Justine de Mott, Isolde M. Larkins, Laura Turnbull, Tracey Warwick, Lacey Willett & Maria M. Allan (2022) The impact of voluntariness of apologies on victims’ responses in restorative justice: findings of a quantitative study, Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 29:4, 593 – 609, DOI: 10.1080/13218719.2021.1956383