Chattahoochee Judicial District: BUCKLE OF THE DEATH BELT: The Death Penalty in Microcosm

- Summary: Chattahoochee--The Death Penalty in Microcosm

- Introduction: Georgia: "The Nation's Executioner"

- Chattahoochee: The Valley of the Shadow of Death

- The Quality of Justice

- Politics of Death

- Victims' Families: A Contrast in Black and White

- Conclusion: A House Divided

Summary: Chattahoochee – The Death Penalty in Microcosm Top

Nearly 20 years after the Supreme Court held the death penalty unconstitutional – largely because of racial discrimination – the death penalty in America continues to reflect the worst aspects of our judicial system: racism, unequal treatment of the poor, a shamefully inadequate legal defense system and abuse of discretion by ambitious prosecutors and other politicians seeking higher office.

The Chattahoochee Judicial District in Georgia is a microcosm of this national disgrace:

- Through the end of 1990, death sentences had been imposed against 20 people, more than in any other district in the state, and nearly twice as many as Atlanta which has three times the population;

- More than half of the black men sentenced to death were tried by all-white juries – after the District Attorney used his discretion (peremptory challenges) to remove every black potential juror;

- While black people account for 65 percent of all homicide victims, the DA seeks the death penalty almost exclusively in white victim cases;

- Families of white murder victims are treated with dignity and respect by the DA’s office, while black victims’ families are abused or ignored;

- For many years, a white public defender – appointed by elected white judges – refused to challenge systematic underrepresent-ation of blacks in the jury pool “for fear of incurring the community’s hostility;”

- The DA has sought the death penalty in nearly 40 percent of the cases where the defendant was black and the victim white, in 32 percent of the cases where both defendant and victim were white, in just 6 percent of the cases where both defendant and victim were black and never where the defendant was white and the victim black.

By executing more people than any other state, 80 percent of them black, Georgia has earned the title, “The Nation’s Executioner.” The legal history of the death penalty in America can be traced in Georgia cases: Furman vs. Georgia (1972), which held the death penalty unconstitutional largely because of discrimination by race; Gregg vs. Georgia

(1976), which found the new death penalty constitutional with its two-part guilt/penalty phase trials guiding jury discretion; Coker vs. Georgia (1977), holding the death penalty unconstitutional for the crime of rape – again in part because of a history of discrimination; and McCleskey vs. Kemp (1987), which held the death penalty constitutional despite strong evidence that race of victim is the most important variable in predicting who will be sentenced to death.

The quality of counsel in capital cases is a national disgrace, but nowhere more so than in the South. In most southern states, there is no statewide indigent defense system. Lawyers are so poorly reimbursed that they are often working for less than minimum wage. On occasion, lawyers who have never tried a single criminal case at all are appointed to represent defendants facing the death penalty. According to a comprehensive report in The National Law Journal (6/11/90), lawyers in capital trials in the South have been “suspended, disbarred or otherwise disciplined at a rate (up to) 46 times the discipline rates” for other lawyers in those states. It is not uncommon for all-white juries to sentence black men to death in the electric chair after less than an hour’s deliberation. In one recent Chattahoochee case, after the federal court reversed just such a death sentence, competent lawyers assigned to the case resisted the DA’s attempts to remove black jurors. As a result, a jury which included blacks sentenced the same defendant to life in prison.

The role of race in determining who will receive society’s ultimate sanction is not restricted to the South:

- In Philadelphia, a single judge is responsible for sentencing 26 people to death – two of whom were white;

- A Native American in California had his original death sentence reversed because of prevailing racism in the sentencing county, and was acquitted at retrial in a different county;

- Of the 148 people executed nationwide since 1977, nearly 90 percent were sentenced for killing white people, though black people continue to be the victims of murder at a rate six times greater than white people;

- Since the death penalty was reinstated in the 1970s, not a single white person has been executed for taking the life of a black person.

This report, whose main focus is the Chattahoochee Judicial District in Georgia, should be viewed as a window into a nationwide system that is inherently unfair, tainted by political considerations in the exercise of discretion, and plagued by prevailing racial bias.

To Dr. Joseph Lowery, President of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, the death penalty “perpetuates the ugly legacy of slave times, teaching our children that some lives are inherently less precious than others.” This report should be read in light of that indictment.

Defense Attorney Stephen Bright to District Attorney Doug Pullen, in death penalty trial of William Anthony Brooks:

”…these five black men were all tried by all-white juries and defended by white lawyers, prosecuted by white prosecutors, and tried by white judges. Does that offend your sense of justice?”

Judge Hugh Lawson, interrupting:

“What does his sense of justice have to do with it?”

Death Penalty Information Center

DPIC with the support of The Southern Christian Leadership Conference

1320 Eighteenth Street, NW, 5th Floor, Washington, DC 20036

202 – 293-6970 /Fax: 202 – 822-4787 by Michael Kroll former Executive Director, Death Penalty Information Center 1991

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Summary: Chattahoochee – The Death Penalty in Microcosm

Introduction: Georgia, The Nation’s Executioner

Chattahoochee: The Valley of the Shadow of Death

The Quality of Justice

Politics of Death

Victims’ Families: A Contrast in Black and White

Conclusion: A House Divided

“I have known for a long time justice has two faces: one white and one black.”

–Judge Albert Thompson, retired

Chattahoochee Judicial District

Introduction: Georgia: “The Nation’s Executioner” Top

INTRODUCTION:

Georgia: “The Nation’s Executioner”

With more than 2,400 people under sentence of death and nearly 150 executions carried out since the ten-year death penalty moratorium ended in 1977, capital punishment continues to be plagued by controversy. Nowhere is this controversy more intense or more starkly apparent than in Georgia, which has earned the title, “The Nation’s Executioner,” by having carried out more executions than any other state. The fact that over 80 percent of those executed were black helped persuade the U.S. Supreme Court in 1972 to invalidate death penalty statutes across the country.

In that decision, Furman vs. Georgia, the high Court held the death penalty unconstitutional as applied, arbitrary and capricious, and “pregnant with discrimination.”[1] Former Justice Potter Stewart wrote, “…if any basis can be discerned for the selection of these few to be sentenced to die, it is the constitutionally impermissible basis of race.”[2]

Five years later, another Georgia case, Coker vs. Georgia, ended the practice of executing rapists. Race, again, played a pivotal role in the decision. From 1930, when the government first began compiling such data, 62 men had been executed in Georgia for the crime of rape. Four of them were white. 58 of them – 94 percent – were black.[3]

Since adoption of its current death penalty law in 1973, Georgia has executed 14 people – ten black and four white. Thirteen of fourteen were electrocuted for killing white people, though black citizens are significantly more likely to be murder victims than white citizens. In these respects, the picture since Furman mirrors the state’s pre-Furman picture. By 1987, another Georgia case came under review by the U.S. Supreme Court. In McCleskey vs. Kemp, the defendant presented evidence demonstrating a strong, statewide statistical link between race of victim and the imposition of death. The data – accepted as valid by the Court – revealed that prosecutors sought the death penalty in 70 percent of the cases where black defendants were implicated in the killing of white people, but only 19 percent of the cases implicating white defendants in the murder of black people.[4]

McCleskey’s evidence persuaded the Court that “a discrepancy that appears to correlate with race” existed in Georgia’s death sentences, but described the disparities as “an inevitable part of our criminal justice system,”[5]and declined to find a constitutional violation.

The four-member minority on the Court was disturbed that “there is a better than even chance in Georgia that race will influence the decision to impose the death penalty: a majority of defendants in white-victim crimes would not have been sentenced to die if their victims had been black.”[6] This was not enough, however, to persuade the majority.

The assumptions that underlay the Court’s majority (5 – 4) decision in McCleskey are worth noting:

* That even the most sophisticated study of sentencing patterns can only demonstrate a degree of risk that race influences some death penalty decisions, and not that it influenced any particular decision;

* That to violate the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment, it would have to be shown that McCleskey’s decision makers had acted purposefully to discriminate;

* That each death penalty is meted out by a jury “selected from a properly constituted venire;”

* That the courts have “engaged in unceasing efforts to eradicate racial prejudice from our criminal justice system.”[7]

The Chattahoochee Judicial District in southwest Georgia offers a highly focused view into the actual use of the death penalty, providing numerous examples that test those underlying assumptions.

Chattahoochee: The Valley of the Shadow of Death Top

The six-county Chattahoochee Judicial District includes Georgia’s second largest city, Columbus, and the huge military base at Fort Benning. Across the Chattahoochee River to the west lies Alabama.

From 1973, when Georgia’s newly-enacted death penalty statute went into effect, until the end of 1990, there have been 28 capital cases tried, resulting in 20 death sentences – 75 percent more than Atlanta with nearly three times the population.

These statistics, and the experiences they reflect for Columbus’ black citizens, have completely undermined any faith that the judicial system deals fairly and equitably with African-Americans. According to a recent poll in the Columbus Ledger-Enquirer, “…large numbers of the city’s black residents feel that blacks do not receive the same treatment as whites in the criminal justice system.”[8]

Gary Parker, who has represented both capitally charged black defendants in court as well as the city of Columbus in the State Senate, says, “When it comes to the death penalty, we have two systems of justice – one for those who kill whites, and an altogether different one for the killers of blacks.”[9]

The Quality of Justice Top

THE QUALITY OF JUSTICE

The notion of “Equal Justice Under Law,” so undermined by racial bias, is further eroded by the quality of legal representation in capital cases.

The American Bar Association found “the inadequacy and inadequate compensation of counsel at trial (to be) the principal failing” of the capital punishment system today.[10] It was precisely this failing that prompted The National Law Journal, in its thorough study of the quality of legal counsel in capital cases in the South, to conclude that “southern justice in capital murder trials is more like a random flip of the coin than a delicate balancing of the scales” because lawyers who defend the accused are “too often ill-trained, unprepared and grossly underpaid.”[11]

In Alabama, a capital trial had to be delayed for a day when the defense lawyer came to court drunk and had to spend the night in lock-up. The trial resumed the next morning, and his client was sentenced to death. One-fourth of those condemned to death in Kentucky were represented by lawyers who have since been disbarred, suspended or imprisoned. In four different capital trials in Georgia, defense lawyers referred to their clients as “nigger.” The death penalty was imposed in all four.

Compensation for lawyers in capital cases virtually guarantees bargain-basement justice. Arkansas limits total compensation of defense counsel in capital cases to $1,000. Alabama places a similar cap on out-of-court time. In one Georgia circuit, capital cases are assigned on a low-bid basis. In these circumstances, defendants facing the death penalty are represented by lawyers who do not earn enough even to pay their office overhead.

The American Bar Association’s 1989 national study of death penalty trials and appeals spared few states from criticism, but Georgia was especially singled out. The report of the death penalty task force, chaired by conservative California Supreme Court Chief Justice, Malcolm Lucas, found:

“Georgia’s recent experience with capital punishment has been marred by examples of inadequate representation, ranging from virtually no representation at all… to representation by inexperienced counsel, to failure to investigate basic threshold questions, to lack of knowledge of governing law, to lack of advocacy on the issue of guilt, to failure to present a case for life at the penalty phase.”

In one recent case, a lawyer just admitted to the Georgia bar and employed by a civil firm in Columbus for less than a week, visited the courthouse on a Wednesday where she met the judge. Two days later, the judge phoned and appointed her to handle the direct appeal of a man just sentenced to death. It was the first case of any kind she had ever handled.

Perhaps no case better illustrates the quality of justice in the Chattahoochee Judicial District than that of William Anthony Brooks.

In 1977, Brooks was tried for the rape/murder of a white Columbus resident, Jeanine Galloway. Mr. Brooks is black. It is the kind of high-visibility, media-genic case that so often serves to advance the political careers of elected prosecutors, a fact not lost on then District Attorney Mullins Whisnant or his assistant, William Smith, both of whom are now judges. Brooks’ case was the first televised death penalty trial in Georgia.

When the case came to trial, black citizens were, as a matter of routine practice, underrepresented in the jury pool.[12] Historically, black citizens had been excluded from serving on juries in this part of Georgia. In more recent times, the pattern of underrepresentation of blacks continued partly because the public defender – appointed by the elected white judge – refused to challenge the practice on behalf of his black clients “for fear of incurring hostility from the community.”[13]

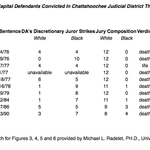

There were only eight blacks among the 160 jurors summoned for the trial of William Brooks in 1977. A fair representation among 160 potential jurors would have included 50 black citizens. Three of the eight were disqualified by the judge during jury selection. Using his discretionary power to remove potential jurors, DA Whisnant struck all the remaining blacks from the jury.

After finding him guilty, it took the all-white jury less than an hour to sentence Brooks to death in the electric chair.

The verdict was set aside in 1986 by the U.S. 11th Circuit Court of Appeals, not because the jury was skewed by the judicial process, but because an instruction from the judge unconstitutionally shifted the burden of proof from the government to prove guilt to the defendant to prove innocence. (About 70 percent of Georgia’s death judgments are overturned by higher courts).

When the case was returned to Columbus for trial, Brooks was represented by the same lawyers who had won the reversal in the 11th Circuit: Stephen Bright, of the Southern Prisoners’ Defense Committee (now The Southern Center for Human Rights), and George Kendall of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund. They brought on board Gary Parker, a black state senator from Columbus.

What happened thereafter demonstrates that good lawyering is the difference between life and death in capital cases. First, they obtained a change of venue, arguing successfully that pre and post-trial publicity – plus the fact that the trial itself had been televised – had made finding a fair and impartial jury in Columbus impossible.

Second, in a series of pre-trial motions, they sought to meet the challenge of McCleskey, moving to prevent the District Attorney from even seeking the death penalty “because of racial discrimination in the prosecution of this case by the current District Attorney… and his two predecessors in office…”[14]

Ultimately, the motion failed, but not before the defense was able to put on evidence of the disparate treatment of blacks and whites that, consciously or not, was the routine practice of the office of the District Attorney.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, prosecutor Pullen continued to discriminate, using all ten of his discretionary jury strikes to remove blacks. Despite his efforts, however, after jury selection was completed, eight blacks remained seated on the jury.

In the same amount of time it had taken the first jury to sentence Mr. Brooks to death, it took the second jury to sentence him to life. In the first trial, according to attorney Bright, “the outcome was known before it even started. (This trial proves) what I’ve always thought: that if we had a fair trial by a representative jury, he would be sentenced to life imprisonment.”[15]

As in Brooks’ case, a “fair trial” often means physically removing the case from the political influences that drive the death penalty. Far too often, however, those influences can not be evaded.

Politics of Death Top

In 1988 the death penalty became the most prominent political symbol in the national elections, helping propel George Bush forward while hobbling his opponent. Candidates in countless races for governor and state senator and assemblyperson, in countless states aped the President’s campaign, and did him better. In some races, macabre competitions seemed to erupt as to who could kill the most murderers the fastest.

These statewide and national campaigns were very visible, even though they failed as often as they succeeded. Newspapers wrote about them, television news reported them. But the real impact of the politics of death is at the other end of the process where decisions are made by local DAs as to which cases to plea bargain, which to seek life and which death.

What is not visible on the national screen is how politicians manipulate the death penalty at the lowest levels, at the beginnings of the political system. It is here, after all, that decisions about the death penalty make a real difference to individual lives. It is especially here, in the rural South where a vastly disproportionate number of death cases arise, that the death penalty has launched many a local District Attorney into the political limelight which is but a short jump to a judgeship.

Because judges are elected at large, they must literally appeal to the masses. It is no surprise, in this environment, to find highly publicized death penalty trials easily and often serving as the vehicle for that appeal. For DAs, the best cases involve the most emotionally charged set of facts of all: a black defendant and a white victim. With a trial like that going on, the DA can pretty much count on the newspaper and television to give him a daily platform.

Since 1973, when Georgia’s current death penalty statute took effect, Columbus has had three district attorneys. Douglas Pullen, the current DA, served as assistant to both of his predecessors.

Mullins Whisnant served from 1970 to 1977. During his tenure, the death penalty was sought against five black men tried by all-white juries (Joseph Mulligan, Jerome Bowden, Johnny Lee Gates, Jimmy Lee Graves and William Brooks). Except for the life sentence meted out to the seriously mentally troubled 16-year-old, Jimmy Lee Graves, each received a death sentence. Mulligan and Bowden, have already been executed.[16]

In the evidentiary hearing prior to Mr. Brooks’ second trial, attorney Bright tried to get an explanation from the former DA who is now a judge about the racial make-up of the juries in those cases, but presiding judge, Hugh Lawson, would not permit it:

“Now, it’s fair to say that an all-white jury doesn’t represent this community does it?“Former DA Whisnant: “No, I wouldn’t say that that’s true. I’d say they could fairly represent this community.”

Judge Lawson: “Well, why do you ask the question?”

Bright: “Because the juries don’t represent the community.”

Judge: “Well, there’s no requirement that they do.”\par Bright: “Well, I don’t think that’s completely true, Your Honor.”\par Judge: “Well, the Court tells you that’s true.”\par Bright:“Well, we’re talking about discrimination and we’re talking about the fact that all-white juries were trying capital cases during Judge Whisnant’s term of office… five black men tried by all-white juries. I ask the same question I asked earlier, is that fair, black people being tried by all-white juries?”

Judge: “I rule that that’s not relevant.”[17] Motion to bar the death penalty in the case of State of Georgia vs. William Anthony Brooks

The last capital case tried by Mullins Whisnant as District Attorney was in November, 1977 – William Brooks’ first trial. Following that trial, Georgia’s first ever televised, the DA was appointed to the superior court by the governor. That is where he presides today.

His successor, William J. Smith, who assisted in prosecuting the Brooks case, followed a similar path to the bench. In 1979, he prosecuted the capital case of William Spicer Lewis, a black man. By using eight of nine discretionary challenges against black potential jurors, Smith got an all-white jury which sentenced Lewis to death.

In yet another black-defendant murder case, that of William Henry Hance, then DA Smith used seven of eight strikes to remove black potential jurors, leaving one black citizen on the jury. When the death sentence was reversed, the DA called a press conference to denounce the decision.

When William Spicer Lewis’ death sentence was reversed by a higher court, it came back for resentencing before the only black judge ever appointed to sit in the Chattahoochee Judicial District. Judge Albert Thompson resentenced Lewis to life in prison, and was immediately denounced at a press conference called by DA Smith. Judge Thompson was defeated in the next election.

When William Brooks’ case was reversed by the U.S. 11th Circuit Appeals Court, Mr. Smith again called a press conference – after conferring with the victim’s family – to announce that he would again seek the death penalty.

In another highly publicized case in which the victim was the daughter of a prominent white contractor, Mr. Smith phoned to ask the contractor personally what punishment he wanted the DA to seek. When the contractor told him to go for the death penalty, Smith told him that was all he needed to hear. He secured a death sentence and was rewarded with a $5,000 contribution – his largest single contribution – to run for judge in the next election.

In 1988, D.A. Smith was elected to the superior court bench where he presides today.

Victims’ Families: A Contrast in Black and White Top

The evidentiary hearing on the motion to prohibit District Attorney Pullen from seeking the death penalty in the retrial of William Brooks produced some startling testimony. Former DAs Whisnant and Smith, and present DA Pullen all testified that it was their practice to keep victims’ families fully informed of the proceedings.

“I generally will meet with the family and introduce myself, and this is something I’ve done for years and years,” Pullen testified. “(I) tell them that I’ll be prosecuting the case and try to explain to them what the procedure is.”[18]

A succession of family member witnesses, however, exposed the DAs practice to be somewhat one-sided: when the victim is white, the DA is solicitous of the family’s feelings, often paying them courtesy visits at their homes and then announcing, at a press conference, that he will be seeking the death penalty in accordance with the family’s wishes.

A parade of black witnesses, however, who had lost one or more family members to murder, revealed a clear pattern of neglect, even abuse at the hands of officials. Not only did none of the murders of their relatives lead to a capital trial, but officials often treated them as criminals:

- Jimmy Christian was informed by the police in 1988 that his son had been murdered. That was the last he heard from any officials. He was never advised of any court proceedings. When an arrest was made, he heard about it on the street. He was not informed of the trial date or the charges.[19]

- Johnny Johnson came home from church in 1984 to find the body of his wife, her throat cut. His one contact with officials occurred when he was briefly jailed on suspicion of her murder. Ultimately, an arrest was made, but Mr. Johnson was not informed either of the arrest or of the trial and sentencing. “They didn’t tell me nothing,” he testified.[20]

- Gloria Tell’s daughter was murdered in 1984. She learned by reading the papers that her daughter’s boyfriend had committed the murder. She was only informed of the preliminary hearing when she phoned the county jail to inquire. No one from the DA’s office ever bothered to contact her.[21]

- Lola Comer’s daughter was murdered in 1981. She heard there was a suspect, and phoned the police to ask if there would be a trial. The case was already resolved, she learned, in a plea bargain, and the perpetrator sentenced to twelve years. No one from the DA’s office talked to her at all. “How did it make you feel?” she was asked on the stand. “It made me feel bad. It hurted me real bad.”[22]

- Mildred Brewer witnessed the shooting of her daughter in 1979. Instead of being allowed to accompany her in the ambulance to the hospital, she was taken to police headquarters and questioned for three hours – during which her daughter died. When a suspect was arrested, indicted, tried and sentenced, Mrs. Brewer heard nothing from the DA.[23]

- Gregory Henderson’s brother was robbed and murdered in 1987, and his girlfriend shot to death. Mr. Henderson was asked to go to the police station to identify the possible perpetrators. Once there, he was physically assaulted by the police and told he was a suspect in his brother’s murder. This went on for a number of hours until his steadfast insistence that he had nothing to do with it persuaded the police to let him leave. He learned later – through the news media – that arrests had been made. No one from the DA’s office ever contacted him or his family about the arrests, the plea bargains, or the jail sentences.[24]

At one point during this litany of abuse and official neglect toward the black community, Judge Lawson tried to cut the process short:

The Court: “All of these people apparently have a relative who was murdered?“Defense Counsel: “That’s correct, Your Honor.”

The Court: “Someone was arrested and ultimately sentenced for the crimes, and each case they will testify they were not contacted by the DA’s office?”

Defense Counsel: “That’s correct,Your Honor.”

The Court: “Is that it? Will the state stipulate…”

The state quickly stipulated to its pattern of discrimination, but defense counsel continued to put the black witnesses on the stand, one after another, since this was the first time they had been offered any opportunity to express any emotion on behalf of their murdered spouses, siblings, parents and children to any officials.

One of the most revealing exchanges of all came between former DA and now Judge William Smith, and attorney Stephen Bright. It was Smith who had originally secured the death sentence against defendant William Brooks. Now, during Brooks’ retrial, he testified that he had kept in close contact with the Galloways, the victim’s family.

But the Brooks family, too, had been victimized by murder. Attorney Bright asked Judge Smith about that:

Bright: “Were you ever in touch with any member of Mr. Brooks’ family?“Smith: “No.”

Bright: “…after his father was killed in 1982.”

Smith: “No.”

Bright: “His sister? His mother? Or anybody?”

Smith: “No.”

Bright: “Did you even know his father was killed?”

Smith: “I wasn’t aware of that.”

Whether conscious or not – aware or not – the effects of race, both as a legacy from the past and an ugly reflection of prejudice today, continue to play a primary role in determining who will pay society’s ultimate sanction. Fatal to the notion of Equal Justice Under Law – that lofty principle inscribed in stone above the entrance to the Supreme Court – racism and its applications in the death penalty process are not confined to Georgia’s Chattahoochee Judicial District.

Just across the Chattahoochee River, two minutes from downtown Columbus, lies Russell County, Alabama. There, a severely mentally impaired black man, George Daniel, awaits retrial. Daniel was convicted and sentenced to death for killing a police officer in 1981. The victim, Officer Claypool, had tried to arrest Daniel for wandering from house to house looking for a place to stay. Daniel resisted; the two struggled. In the course of the struggle, the officer was shot.

Last year, the federal District Court determined that Daniel’s counsel had provided inadequate representation at trial. Seeking to discredit Daniel’s incriminating statement, his lawyers had asked witness after witness if they knew of any black person who spoke as well.

In the course of reinvestigating the case, new attorneys discovered that the state’s expert witness, a staff “psychologist” for eight years at the state mental hospital who had testified that Daniel had no mental health problems, was a fraud. Although his employment history included work as a prison guard in California and Arizona, he was not a psychologist and never had been.

In another Russell County case, the District Attorney struck every black prospective juror, leaving an all-white jury to sentence Robert Tarver. Despite that, the jury split 8 – 4 in favor of a life sentence. Casting his lot with the four, the judge simply ignored the majority’s recommendation for life, and imposed a death sentence. Alabama is one of three states (Florida and Indiana are the others) which permit judges to impose death over a jury’s decision to spare the defendant – and about one of every four Alabama death sentences was imposed despite the jury’s contrary recommendation.

Bordering Russell County is Chambers County, notorious for the lack of legal resources and the delays in providing counsel for indigent defendants (one black man waited in jail for three and half years on a capital offense before seeing an attorney). It is also a place where official marriage records are still kept in books engraved with the unmistakable words, “white” and “colored.”[25]

Albert Jefferson was sentenced to death by an all-white Chambers County jury. The District Attorney in the case appealed to the jury’s racial fears, suggesting that a death sentence would “send them a message” because “they’ve been coming into our neighborhoods.” There is little doubt who “they” are.

Before selecting his jury in the Jefferson case, the prosecutor ranked the 101 prospective jurors into four categories: “strong,” “medium,” “weak” and “black.” He exercised all 26 of his discretionary strikes in selecting his jury – all against black citizens. Not a single white was struck, a fact acceptable to the presiding judge. Apparently, the “weakest” white was preferable to the “strongest” black.[26]

Such examples abound:

- Every execution of a juvenile offender in Louisiana since slavery has followed one pattern: black defendant, white victim, all-white jury;

- The Florida Supreme Court’s Racial and Ethnic Bias Study Commission released its report late in 1990 finding unfair treatment of minorities in every aspect of the criminal justice system;

- A Native American prisoner sentenced to death in California had his sentence overturned because of the prevailing racial biases in the community, was retried in a different county, and was acquitted;

- A single judge in Philadelphia, PA, is respons-ible for sentencing 26 people to death (20 percent of the state’s total). Of these, only two were white.

Conclusion: A House Divided Top

Former Columbus Superior Court Judge, Albert Thompson, recently described the justice system as having “two faces: one white and one black.”[27] Unfortunately, this observation is not limited to a single judicial district. The Chattahoochee Judicial District in Georgia is a microcosm of death penalty practices in this country, both historically and currently. While state resources to seek death are virtually unlimited, defense lawyers are severely hobbled by lack of money, not just for their own time but for the services of investigative and mental health experts. Local politics provide irresistible incentives for ambitious prosecutors to turn white-victim murder cases into dramatic vehicles for their ambition, especially when the defendant is black. Official racism manifests itself repeatedly in capital trials, from choosing which cases to select for death and which to plea bargain, to keeping families of victims informed or not, to striking black prospective jurors, to resorting to press conference theatrics to denounce unfavorable decisions.

Tried by an all-white jury in a highly politically-charged environment, William Brooks was sentenced to death in less than an hour. Retried by competent counsel whose aggressive efforts ensured that black citizens were fairly represented on the jury, Brooks was resentenced to life.

The tragedy is that few who face society’s ultimate penalty are as fortunate as Mr. Brooks. Few come to the attention of the small cadre of attorneys trained in the intricacies of capital litigation. Fewer, still, are able to secure the services of those overworked attorneys.

The difference, as Mr. Brooks’ case makes clear, is that between death and life. It is as if a patient suffering an extremely rare form of brain cancer were forced to be treated by a general practitioner with the bare minimum qualifications and no instruments, instead of a skilled specialist with the proper tools and assistants. The difference is between death and life.

While this report was being prepared, two new death penalty cases were decided in Columbus. On the same day – Sunday, February 10 – two separate juries returned verdicts in two separate cases.

James Robert Caldwell, notorious for raping and murdering his 12-year-old daughter and stabbing his 10-year-old son nearly to death, was sentenced to life in prison. Mr. Caldwell is white.

It took jurors just over an hour to sentence Jerry Walker to death in the electric chair. He murdered a convenience store clerk in the course of a robbery – the son of a prominent, white military official at neighboring Fort Benning. After his former boss in the DA’s office, now Judge Mullins Whisnant set the date for Mr. Walker’s execution, District Attorney Doug Pullen said, “The first step of justice has been served.” Mr. Walker is black.[28]

Since the Furman decision in 1972, we have had nearly twenty years of experience to test the fairness of the modern death penalty. That experience demonstrates once again that the intractable problem of racial discrimination is at the heart of its application. As long as the political process governs decision making in regard to capital punishment, the death penalty will continue to be applied to as it always has been, to America’s powerless: racial minorities, the poor and the mentally disabled. The problem, national in scope, demands national solutions.

There are things which can be done to minimize the pernicious effects of race and class in death penalty litigation. To begin with, competent legal counsel should be the right of everyone facing a capital trial, the most complex of all criminal procedures. To achieve even a semblance of fairness, minimal standards of competency – of training and experience – must be required of those appointed to represent capitally charged defendants at trial. Adequate compensation and resources for expert advice must be guaranteed. To provide less is to perpetuate a national disgrace.

Second, Congress must address the race question head-on. The crime bill reported out of both the Senate and House Judiciary Committees in 1990 included a provision called the Racial Justice Act which provides to the condemned the same mechanism now available to those who allege race bias in housing and employment: the right to show, through statistics and other evidence, an unconstitutional pattern and practice of racial discrimination in the application of the death penalty by the decision makers in that case.

The bill foundered last year because the Senate failed to pass the Racial Justice Act. This year, Congress again will have an opportunity to implement the Racial Justice Act. It is long-since time such a remedy were part of the federal law.

April 22, 1990, marked the fourth anniversary of the Supreme Court’s decision in McCleskey vs. Kemp. In light of what still passes for justice in the Chattahoochee Judicial District, in Georgia and in the nation, the words of now retired Associate Justice William Brennan in that case ring with a special clarity. Writing in dissent against the decision of the five-member majority, he warned:

“…we remain imprisoned by the past as long as we deny its influence in the present. It is tempting to pretend that minorities on death row share a fate in no way connected to our own, that our treatment of them sounds no echoes beyond the chambers in which they die. Such an illusion is ultimately corrosive, for the reverber-ations of injustice are not so easily confined.”

References

[1] Justice William O. Douglas, concurring, Furman vs. Georgia (408 U.S. at 257)

[2] Ibid. Justice Potter Stewart, concurring at 310

[3] Brief for Petitioner in Coker vs. Georgia, 433 U.S. 584 (1977)

[4]McCleskey vs. Kemp, 481 U.S. 279 (1987)

[5] Ibid. From the majority opinion of Justice Powell at 31

[6] Ibid. From the dissenting opinion of Justice Brennan at 9

[7] Ibid. From the majority opinion of Justice Powell at 9 – 12 and 27

[8] “Racism Concern is Nothing New in Columbus,”] Columbus Ledger-Enquirer, 8/14/88

[9] Statement of Senator Gary Parker to the U.S. House of Representatives Subcommittee of the Judiciary on Civil and Constitutional Rights, May 9, 1990

[10] “Toward a Most Just and Effective System of Review in State Death Penalty Cases,” American Bar Association, August, 1990

[11] “Fatal Defense,” The National Law Journal, June 11, 1990

[12] See ]Peters vs. Kiff, 407 U.S. 493 (1972); ]Gates vs. Zant, 863 F.2d 1492 (11th Cir. 1989)

[13] Op. Cit. at 12

[14]State vs. William Anthony Brooks, “Motion to Bar the Death Penalty”

[15] “Brooks Gets Life Sentence in ’77 Galloway Murder,” ]Columbus Ledger-Enquirer, 1/24/91

[16] Jerome Bowden was Georgia’s final execution of a mentally retarded defendant. The public revulsion generated by his execution prompted the legislature to prohibit the execution of the mentally retarded, the first state to do so. (Four other states have since followed Georgia’s lead). Official Code of Georgia, Annotated SS17‑7 – 31

[17] Motion to bar the death penalty in the case of State of Georgia vs. William Anthony Brooks, Volume V at 170 – 171

[18] Ibid. at 178

[19] Ibid. at 180 – 185

[20] Ibid. at 196 – 201

[21] Ibid. at 204 – 206

[22] Ibid. at 209 – 213

[23] Ibid. at 226 – 229

[24] Ibid. at 214 – 215

[25] Senator Gary Parker, Op. Cit., at 13

[26]State vs. Jefferson, Circuit Court of Chambers County, Alabama, No. CC-81 – 77

[27] “The Color of Justice,” Columbus Ledger-Enquirer, 5/19/91

[28] “Caldwell Sentenced to Life in Prison in Daughter’s Death,” “Walker Gets Death Sentence for 1988 Store Clerk Slaying,” Columbus Ledger-Enquirer, 2/11/91

[29]McCleskey vs. Kemp, Op. Cit., Brennan dissenting