The Death Penalty in 2020: Year End Report

Death Penalty Hits Historic Lows Despite Federal Execution Spree

Pandemic, Racial Justice Movement Fuel Continuing Death Penalty Decline

Posted on Dec 16, 2020

- Introduction

- Death penalty developments in the states and counties

- Federal Death Penalty

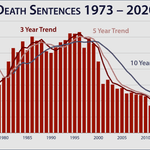

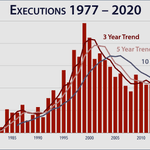

- Execution and Sentencing Trends

- Innocence

- Clemency

- Problematic Executions

- New Sentences Continue to Highlight Systemic Death Penalty Flaws

- Impact of the Pandemic

- Public Opinion and Election Results

- Racial Justice

- Supreme Court

- Key Quotes

- Downloadable Resources

Key Findings

- Colorado becomes 22nd state to abolish death penalty

- Reform prosecutors gain footholds in formerly heavy-use death penalty counties

- Fewest new death sentences in modern era; state executions lowest in 37 years

- Federal government resumes executions with outlier practices, for first time ever conducts more executions than all states combined

- COVID-19 pandemic halts many executions and court proceedings; federal executions spark outbreaks

This report was updated on December 22 to reflect the exoneration of Roderick Johnson in Pennsylvania.

Introduction Top

2020 was abnormal in almost every way, and that was clearly the case when it came to capital punishment in the United States. The interplay of four forces shaped the U.S. death penalty landscape in 2020: the nation’s long-term trend away from capital punishment; the worst global pandemic in more than a century; nationwide protests for racial justice; and the historically aberrant conduct of the federal administration. At the end of the year, more states had abolished the death penalty or gone ten years without an execution, more counties had elected reform prosecutors who pledged never to seek the death penalty or to use it more sparingly; fewer new death sentences were imposed than in any prior year since the Supreme Court struck down U.S. death penalty laws in 1972; and despite a six-month spree of federal executions without parallel in the 20th or 21st centuries, fewer executions were carried out than in any year in nearly three decades.

The historically low numbers of death sentences and executions were unquestionably affected by court closures and public health concerns related to the coronavirus. But even before the pandemic struck, the death sentences and executions in the first quarter of the year had put the United States on pace for a sixth consecutive year of 50 or fewer new death sentences and 30 or fewer executions. The execution numbers also were skewed by a rash of executions that marked the federal government’s death-penalty practices as an outlier, as for the first time in the history of the country, the federal government conducted more civilian executions than all of the states of the union combined.

Death Row By State†

| State | 2020 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|

| California | 724 | 729 |

| Florida | 346 | 348 |

| Texas | 214 | 224 |

| Alabama | 172 | 177 |

| North Carolina | 145 | 144 |

| Pennsylvania | 142 | 154 |

| Ohio | 141 | 140 |

| Arizona | 119 | 122 |

| Nevada | 71 | 74 |

| Louisiana | 69 | 69 |

| U.S. Government | 62 | 61 |

| Tennessee | 51 | 56 |

| Oklahoma | 47 | 46 |

| Georgia | 45 | 51 |

| Mississippi | 44 | 44 |

| South Carolina | 39 | 40 |

| Arkansas | 31 | 32 |

| Kentucky | 28 | 30 |

| Oregon | 27 | 32 |

| Missouri | 22 | 24 |

| Nebraska | 12 | 12 |

| Kansas | 10 | 10 |

| Idaho | 8 | 8 |

| Indiana | 8 | 9 |

| Utah | 7 | 8 |

| U.S. Military | 4 | 4 |

| Virginia | 2 | 3 |

| Montana | 2 | 2 |

| New Hampshire^ | 1 | 1 |

| South Dakota | 1 | 2 |

| Wyoming | 1 | 1 |

| Colorado^^ | 3 | |

| Total | 2591‡ | 2656‡ |

^New Hampshire prospectively abolished the death penalty May 30, 2019

^^Colorado abolished the death penalty on March 23, 2020 and Gov. Jared Polis granted clemency to the three men on death row

† Data from NAACP Legal Defense and Educational

Fund for July 1 of the year shown

‡ Persons with death sentences in multiple states

are only included once

The erosion of capital punishment at the state and county level continued in 2020, led by Colorado’s abolition of the death penalty. Two more states — Louisiana and Utah – reached ten years with no executions. With those actions, more than two-thirds of the United States (34 states) have now either abolished capital punishment (22 states) or not carried out an execution in at least ten years (another 12 states). The year’s executions were geographically isolated, with just five states, four of them in the South, performing any executions this year. The Gallup poll found public support for the death penalty near a half-century low, with opposition at its highest level since the 1960s. Local voters, particularly in urban centers and college towns, rejected mass incarceration and harsh punishments, electing new anti-death-penalty district attorneys in counties constituting 12% of the current U.S. death-row population.

A majority (59%) of all executions this year were conducted by the federal government, which in less than six months carried out more federal civilian executions than any prior president in the 20th or 21st centuries, Republican or Democratic, had authorized in any prior calendar year. The Trump administration performed the first lame-duck federal execution in more than a century, while scheduling more transition-period executions than in any prior presidential transition in the history of the United States. The executions reflected systemic problems in the application of capital punishment and drew widespread opposition from prosecutors, victims’ families, Native American leaders, religious leaders, regulatory law experts, and European Union officials. In addition to the legal issues, the executions also presented public health problems, likely sparking an outbreak in a federal prison, infecting members of the execution teams, and causing two federal defense attorneys to contract COVID-19.

Death sentences, which were on pace for sustained low levels prior to the pandemic, plunged to a record low of 18. While the resumption of trials delayed by the pandemic may artificially increase the number of death verdicts over the next year or two, the budget strain caused by the pandemic and the need for courtroom space to conduct backlogged non-capital trials and maintaining a functioning court system may force states to reconsider the value and viability of pursuing expensive capital trials.

Executions and new death sentences in 2020 continued to be directed at defendants and prisoners who were the most vulnerable or who had the most defective court process. Every prisoner executed in 2020 had one or more significant mental or emotional impairments (mental illness, intellectual disability, brain damage, or chronic trauma) or was under age 21 at the time of the crime for which he was executed. The executed included several prisoners whose more culpable co-defendants received lesser sentences, a prisoner who was denied potentially exculpatory DNA testing, and prisoners whose executions were opposed by victims’ families. Of those who were sentenced to death this year, more than 20% waived key procedural rights, including their rights to counsel and/or a jury trial, and three strenuously proclaimed their innocence.

Six prisoners were exonerated from death row in 2020. In each of the six cases, prosecutorial misconduct had contributed to the wrongful conviction. The men exonerated this year spent between 14 and 37 years awaiting exoneration. Three of them faced multiple trials, despite evidence of their innocence, and one – Curtis Flowers – was tried six times for the same crime. Pennsylvania exoneree Walter Ogrod contracted COVID-19 and was denied transport to an independent hospital while he waited for a hearing on whether he would be freed.

Landmark state court decisions reflected arbitrariness and bias in the application of capital punishment. The North Carolina Supreme Court issued several rulings overturning the state legislature’s attempt to retroactively repeal the state’s Racial Justice Act. The rulings reinstated life sentences for three former death-row prisoners and paved the way for approximately 140 to obtain hearings on the impact of race discrimination in their cases. A Florida Supreme Court reconstituted after mandatory retirements with activist judges from the Federalist Society, eliminated constitutional and statutory protections for capital defendants and death-row prisoners on four different occasions, but stopped short of taking away resentencing trials for up to 100 prisoners whose death sentences had previously been overturned.

The death penalty has been plagued by inequity and injustice throughout its history, but those problems came into stark focus this year as the pandemic and the protests against police violence highlighted the same disparities throughout our national institutions. As the United States engaged in a nationwide conversation about systemic racism, access to resources, and failures of federal leadership, capital punishment mirrored those faults through its racially biased application, inadequate legal protections, and outlier practices by the federal government.

Death penalty developments in the states and counties Top

Death penalty developments at the state and county level continued the long-term national trend away from capital punishment, as another state abolished the death penalty, two others reached landmarks without executions, and more reform prosecutors gained footholds in formerly heavy-use counties.

In 2020, Colorado became the 22nd state to abolish the death penalty, while Louisiana and Utah each reached 10 years with no executions. As a consequence, more than two-thirds of the country – 34 states – have either abolished capital punishment or have not carried out an execution in more than a decade. Oklahoma, the state that has carried out the third-most executions in the modern era, marked five years since its last execution. Legislative and judicial actions in California, North Carolina, Ohio, and Virginia also signaled the withering of capital punishment, even in high-use states.

Colorado Governor Jared Polis

On March 23, Colorado Governor Jared Polis signed legislation abolishing the death penalty for all future offenses. Governor Polis also commuted the death sentences of the three prisoners on the state’s death row to life without parole. All three of the state’s death row prisoners were Black, and Polis noted the racial disparity in his statement on the commutations. The commutations, he said, were “consistent with the abolition of the death penalty in the State of Colorado, and consistent with the recognition that the death penalty cannot be, and never has been, administered equitably in the State of Colorado.” Two capital prosecutions were pending at the time of abolition but, facing criticism of the futility and wastefulness of the post-abolition pursuit of capital sanctions, the prosecutors dropped the death penalty in both cases.

The pronounced decline of capital punishment in the western U.S. was evident not only in Colorado’s abolition, but also in Utah’s milestone of ten years with no executions. The last execution carried out in Utah was on June 18, 2010, when Ronnie Gardner was executed by firing squad. With this anniversary, only two of the eleven states west of Texas — Arizona and Idaho — still have a death penalty and have carried out an execution in the last decade. Louisiana also marked ten years without an execution, reaching that anniversary on January 7. Twelve of the 28 states (42.9%) that continue to authorize capital punishment have not executed anyone in at least ten years.

Oklahoma, the nation’s third most prolific execution state, reached five years with no executions on January 15. The state’s last three executions were botched or bungled, and the state placed executions on hold after using the wrong drug in the January 15, 2015 execution of Charles Warner and procuring the same wrong drug for the aborted September 30, 2015 execution of Richard Glossip. Just a month after the anniversary of Warner’s execution, the state announced plans to resume executions using the same controversial three-drug protocol that contributed to the string of problematic executions in 2014 and 2015. Litigation is ongoing as death-row prisoners challenge the state’s “risky and incomplete” lethal-injection protocol, which provided no clear plan for addressing the “significant flaws” in training practices identified by the state’s independent Death Penalty Review Commission.

California passed a package of criminal legal reform legislation in August, intended to address racial disparities in the legal system. One bill amends California’s death penalty intellectual disability statute to prohibit the use of race-based IQ adjustments in determining a defendant’s or death-row prisoner’s eligibility for the death penalty; another is directed at racial, ethnic, religious, and gender discrimination in jury selection; and a third – the California Racial Justice Act – seeks to combat racial discrimination in criminal prosecutions and sentencing. The latter two bills apply not only in death-penalty cases, but aim to redress racial bias in any criminal case. The California Racial Justice Act, like the since-repealed North Carolina Racial Justice Act, allows prisoners to use statistical evidence of racial bias to challenge their sentences.

California Governor Gavin Newsom

California Governor Gavin Newsom took further action to tackle racial injustice in the use of the death penalty when he became the first sitting governor in California history to file a friend-of-the-court brief “calling attention to the unfair and uneven application of the death penalty.” In support of the capital appeal of Don’te Lamont McDaniel, Governor Newsom’s brief stated, “Since its inception, the American death penalty has been disproportionately applied, first, to enslaved Africans and African Americans, and, later to free Black people. With this filing, we make clear that all Californians deserve the same right to a jury trial that is fair, and that it is a matter of life and death.”

The North Carolina Racial Justice Act (RJA), which was passed in 2009, but watered down in 2012 and repealed in 2013, was also in the news in 2020. In a pair of rulings on June 5, the North Carolina Supreme Court struck down the state legislature’s attempted retroactive amendment and repeal of the act, restoring the rights of approximately 140 death-row prisoners to challenge death sentences they claimed were substantially affected by racial bias. The rulings in the cases of Andrew Ramseur and Rayford Burke held that “the retroactive application of the RJA Repeal violates the prohibition against ex post facto laws under the United States and North Carolina Constitutions.” It remanded their cases to the trial court to conduct hearings to determine whether their death sentences violated the Racial Justice Act. If the defendants win their challenges, they will be resentenced to life without parole. In three decisions issued on September 25, 2020, the court extended its ruling, directing that prisoners who had proven that their death sentences violated the RJA must be resentenced to life imprisonment without possibility of parole. The court ruled that resentencing Christina Walters, Quintel Augustine, and Tilmon Golphin to death after they had established their entitlement to a life sentence under the RJA violated constitutional principles of double jeopardy and prohibitions against after-the-fact enhancements of punishment, and it restored their life sentences.

A series of Florida Supreme Court decisions stripped protections from criminal defendants and death-row prisoners. In January, the court’s decision in State v. Poole reinstated a death sentence imposed on Mark Anthony Poole in 2011 after a non-unanimous jury had voted to recommend the death penalty. Applying the court’s 2016 ruling in Hurst v. State, a Polk County trial court had overturned Poole’s death sentence and ordered a new sentencing hearing. “Our court … got it wrong,” the justices said, when it ruled in 2016 that death sentences imposed after non-unanimous jury recommendations for death violated the state and federal constitutions. The court’s composition changed drastically in 2019 when three liberal and moderate justices reached mandatory retirement age and were replaced with arch-conservative jurists. Prosecutors sought to apply the Poole ruling to the more than 100 death-row prisoners who had received final orders reversing their death sentences, but who had not yet completed a new sentencing hearing. On November 25, the court unanimously rebuffed those attempts, saying it did not have the power to reinstate those death sentences.

In addition to its decision in Poole, the court also abandoned a century-old standard for heightened review in cases in which a conviction rested solely on circumstantial evidence, limited enforcement of a U.S. Supreme Court case that bars execution of intellectually disabled prisoners, and declared the 50-year-old capital appeal safeguard of proportionality review to be unconstitutional.

In Virginia, legislation reversed an earlier lethal-injection secrecy policy by making the identity of lethal-injection drug suppliers public information subject to disclosure under the state Freedom of Information Act and in civil legal proceedings. With strong bipartisan support, the Virginia Senate also passed a bill to bar the death penalty for individuals who were severely mentally ill at the time of the crime. The measure did not make it out of a House subcommittee. A similar measure passed the Ohio House by a 76 – 17 margin, and an amended version passed the Senate in December by a vote of 27 – 3. As this report went to press, the bill had returned to the House for final approval.

Ohio Governor Mike DeWine issued reprieves postponing 11 scheduled executions, citing the state’s inability to obtain execution drugs without placing its supplies of medicines for therapeutic purposes at risk. In an end-of-year news conference, DeWine said that he no longer considered lethal injection a viable method of execution in the state.

In counties across the country, local voters, particularly in urban centers and college towns, brought the national reckoning on racial justice to the ballot box, rejecting mass incarceration and harsh punishments in favor of reform prosecutors. At least nine major counties elected new district attorneys who pledged never to pursue the death penalty or to use it only very sparingly. The movement was led by the election of George Gascón in Los Angeles County, home of the nation’s largest death row. Within hours of being sworn in, Gascón issued directives to halt all capital prosecutions and to review on an individualized basis the cases of the more than 200 prisoners on the county’s death row. New reform prosecutors also were elected in Fulton and Gwinnett counties (Atlanta, Athens) in Georgia; Pima County (Tucson), Arizona; Orleans Parish (New Orleans), Louisiana; Travis County (Austin), Texas; Orange-Osceola Counties (Orlando), Florida; Multnomah County (Portland), Oregon; and Franklin County (Columbus), Ohio. Collectively, those counties comprised 12% of the current U.S. death-row population.

Federal Death Penalty Top

The federal government resumed executions in July 2020 after a 17-year hiatus, with a series of actions that produced controversy and chaos. The sheer number of executions set the Trump administration apart as an outlier in the use of capital punishment, compared both to the historical practices of American presidencies and the contemporary practices of the states in the Union. In addition, the details of the cases and the highly politicized manner in which they were carried out revealed significant problems in the application of the federal death penalty.

The ten people executed under the federal death penalty in the second half of 2020 exceeded the number executed by all of the states combined, the first time in the history of the United States in which the federal government carried out more civilian executions than did the states. The cases selected raised issues about the overt politicization of capital punishment, as well as concerns about lethal injection, Native American tribal sovereignty, disrespect of the wishes of victims’ families, and the constitutionality of executing teenage offenders and individuals with serious mental illness or intellectual disability.

Resuming executions in the midst of a deadly pandemic forced attorneys, religious advisors, media witnesses, and victims’ family members to choose between attending executions and protecting their health and contributed to an outbreak at the correctional complex in Terre Haute that has resulted in multiple prison deaths. At least one member of the federal execution team who attended execution preparation meetings without virus protective gear tested positive for COVID-19 before the executions began and, by mid-December, the executions had exposed hundreds of people to the coronavirus. Shortly after the November 19 execution of Orlando Hall in which execution team members again did not wear virus protective gear, eight members of the execution team who came to Terre Haute from other federal facilities and Hall’s religious advisor tested positive for the virus.

Long-term national trends away from capital punishment, combined with health measures adopted to protect the public from the deadliest global pandemic in more than a century, drove the number of state executions to a 37-year low. But facing the very same factors, the federal government ignored the public health risks in a rush to carry out executions timed for the start of the political parties’ presidential conventions and continuing through and beyond the presidential election. When 2020 concluded, the Trump administration had carried out more federal executions in a calendar year than any presidency in the 20th or 21st centuries and had scheduled more executions for the transition period between presidencies than had ever been carried out in the history of the United States.

Lisa Montgomery

The rash of executions was also aberrant in its selections of prisoners to be put to death. The condemned included the first Native American ever executed by the federal government for a murder of a member of his own tribe on tribal lands; the first federal executions of teenaged offenders in 68 years; the first federal execution in 57 years for a crime committed in a state that had abolished the death penalty; the scheduled executions of two prisoners who medical evidence indicated had intellectual disability; the scheduled executions of two prisoners with serious mental illness, including one who may have been mentally incompetent at the time of his execution; the scheduled executions of two prisoners who did not kill anyone and three who were less culpable than co-defendants who received lesser sentences; the first lame-duck executions in more than a century; and executions carried out against the wishes of victims’ family members, trial or appellate prosecutors in the cases, and at least one of the judges who presided at trial.

The planned execution of Lisa Montgomery, who would have been the first woman executed by the federal government in 70 years, was delayed when her legal team contracted COVID-19 after traveling to meet with her and could not complete her clemency petition. A coalition of more than 1,000 advocates had called for clemency for Montgomery, who is severely mentally ill as a result of horrific abuse throughout her childhood, including being sexually trafficked.

Daniel Lee

The timeline of executions — enabled by U.S. Supreme Court rulings refusing to protect the integrity of judicial review — artificially limited the federal courts’ ability to consider prisoners’ claims, including challenges to the federal execution protocol. The Department of Justice announced the first four execution dates while lethal-injection litigation was still pending in federal court in a case that had previously halted federal executions scheduled in 2019. In the hours leading up to the scheduled execution of Daniel Lewis Lee on July 13, a federal district court in Washington, D.C. issued a preliminary injunction barring all four scheduled federal executions on the grounds that the prisoners were likely to prevail on their challenge to the constitutionality of the execution protocol. Federal prosecutors filed simultaneous motions in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit and the United States Supreme Court seeking to vacate the injunction. As the midnight deadline approached, the appeals court denied the motion, and set an expedited briefing schedule to consider the merits of the district court’s ruling. That schedule, however, extended beyond July 17, effectively halting the first three scheduled executions. In a 5 – 4 decision issued at 2:30 a.m. on July 14, the U.S. Supreme Court wrote that last-minute stay applications were disfavored and that the prisoners had not met the “exceedingly high bar” of establishing that they could show that executions using pentobarbital constitute cruel and unusual punishment.

Because the execution of Wesley Purkey was scheduled just two days after Lee’s, a similarly chaotic series of rulings preceded his execution, with a stay again being lifted by the U.S. Supreme Court in the middle of the night. In both cases, the government left no opportunity to challenge the notice it provided of an immediate morning execution after the original death notice expired. For more details on the rushed executions of Lee, Purkey, and Dustin Honken, read DPIC’s report, The Federal Government Restarts Federal Executions Amid Procedural Concerns and a Pandemic.

Lee and nine other prisoners were executed despite lower federal court rulings that at least one portion of the execution protocol violates federal law. Nonetheless, the Supreme Court has permitted the executions to go forward.

On September 20, the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia found that the execution protocol violates the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act’s premarketing, labeling, and prescription requirements. However, it did not grant a stay on those grounds, allowing the government to proceed with executions using an illegal protocol.

Orlando Hall

The executions of Orlando Hall, Brandon Bernard, and Alfred Bourgeois, carried out in the lame-duck period between the November 3 election and the inauguration of President-elect Joe Biden, marked a stark departure from presidential norms. Orlando Hall was the first person executed by a lame-duck president in more than a century. No administration since Grover Cleveland’s first presidency in 1888 – 1889 had ever carried out multiple transition-period executions. Three weeks after President Trump lost the election, his Justice Department proceeded to set three new execution dates, announce new capital prosecutions it would not be in a position to pursue, and issue a new execution protocol that in certain circumstances could permit the use of controversial back-up methods of execution authorized by some states, including electrocution, hanging, firing squad, and lethal gas. Records uncovered in early December revealed that the Bureau of Prisons sought a no-bid contract for pentobarbital, claiming it was justified under an exception for cases “of such an unusual and compelling urgency that the Government would be seriously injured” if it had to open the contract to competitive bidding. With an incoming administration that has expressed an intention to end the federal death penalty, the Trump administration’s steps to ramp up executions and promulgate a more relaxed regulatory regime for executions seemed particularly spiteful and out-of-step.

Execution and Sentencing Trends Top

Executions By State

| State | 2020 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|

| U.S. Government | 10 | |

| Texas | 3 | 9 |

| Alabama | 1 | 3 |

| Georgia | 1 | 3 |

| Missouri | 1 | 1 |

| Tennessee | 1 | 3 |

| Florida | 2 | |

| South Dakota | 1 | |

| Total | 17 | 22 |

Driven by the combined effects of a global pandemic and the continuing decline in public support for capital punishment, new death sentences and executions reached historic lows in 2020. Though the COVID-19 pandemic had a significant impact on both sentences and executions, the U.S. was poised for its sixth consecutive year with 50 or fewer new death sentences and 30 or fewer executions even before the pandemic shut down court proceedings nationwide.

Fewer new death sentences were imposed in the United States in 2020 than in any other year since the Supreme Court struck down all existing capital punishments statutes in the U.S. in 1972. With counties unable to safely conduct capital trials, states imposed a record low 18 new death sentences, 42% below the previous record low of 31 set in 2016. Most of these sentences (11) were imposed in the first three months of 2020, before courts across the country halted trials as a precaution against the pandemic. Nearly all the death sentences imposed after that time involved judge-only proceedings, consisting of court decisions formally accepting pre-pandemic jury sentencing recommendations or trials in which a defendant waived the right to a jury.

The death sentences that were imposed January through March 2020 put the nation on pace for a sixth consecutive year of fewer than 50 death sentences, a sustained decline of more than 85% from the peak death-sentencing years of the mid-1990s. The temporary closing of courts at the beginning of the pandemic produced the longest stretch of time without a new death sentence since capital punishment was reinstated after Furman. From March to May, 66 days passed without a death sentence being imposed.

Seventeen people were executed in 2020, ten of whom (59%) were executed by the federal government. DPIC’s analysis of historical execution databases indicated that it was the first time in American history that the federal government had executed more prisoners that all of the states combined. Just five states conducted executions, and only Texas carried out more than one. Despite the historically unprecedented federal execution spree, the nationwide total of executions was the lowest in nearly three decades, since eight states carried out fourteen executions in 1991. States carried out the fewest executions in 37 years, when five states executed one prisoner each in 1983.

The racial disparities reflected in this year’s executions continue decades-long trends. Nearly half of the 17 defendants executed in 2020 were people of color (5 Black, 1 Latinx, 1 Native American). Seventy-six percent of the executions were for the deaths of white victims.

Counties With the Most Death Sentences in the Last Five Years

| County | State | New Death Sentences 2016 – 2020 | New Death Sentences 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Riverside | California | 11 | 3 |

| Los Angeles | California | 7 | |

| Maricopa | Arizona | 7 | 1 |

| Clark | Nevada | 6 | |

| Cuyahoga | Ohio | 6 |

Only seven states – Alabama, California, Florida, Mississippi, Ohio, Oklahoma, and Texas – imposed new death sentences this year, and just three – California, Florida, and Texas – imposed more than one. Texas was the only state that both imposed a death sentence and conducted an execution in 2020. Six of the ten federal executions carried out were from death sentences imposed by juries in just two states – Texas (4) and Missouri (2).

Only two counties in the United States – Riverside, California (3 sentences) and Lafayette, Florida (2 sentences) – imposed more than one death sentence, and the Lafayette death sentences were the product of a single trial in which both defendants pled guilty, waived a sentencing jury, represented themselves, and presented no case for life. This was the third time in the last five years that Riverside County led the nation in death sentences. The fifteen counties that imposed death sentences represent less than half of one percent of all U.S. counties.

Nearly three-quarters (73%) of execution dates scheduled in 2020 were halted in some way. Of the 62 dates scheduled this year, only 17 were carried out. One execution – that of Jimmy Meders in Georgia – was halted by commutation. Nineteen executions were stayed. Sixteen executions were halted by reprieve, 14 of which were Ohio executions delayed because of problems with the state’s execution protocol. The other two reprieves came in cases in which Tennessee Governor Bill Lee delayed executions as a result of pandemic-related concerns. Nine execution warrants were withdrawn, removed, or rescheduled.

Six of the stays cited the COVID-19 pandemic and its impacts on the legal process. Six were legally premature warrants issued in Pennsylvania and Ohio, which were stayed to allow prisoners to complete their guaranteed appeals. Two stays were granted in federal executions that had been scheduled for January 2020, but the federal government issued new warrants for both prisoners later in the year. The remaining stays were issued to permit litigation of case-specific claims, including intellectual disability and access to a spiritual advisor in the execution chamber. The South Carolina Supreme Court stayed what would have been the state’s first execution in nine years because it did not have a supply of execution drugs.

The pandemic is likely to have a continuing influence on the death penalty for the next several years, distorting the numbers of new death sentences imposed and executions carried out. The numbers will remain artificially low until the pandemic subsides, as court closures and continuances delay death penalty trials and push back death warrants and executions. Once courts return to full functioning, we are likely to see artificial pandemic-related increases in both new death sentences and executions. Because of these distortions, it will likely be several years before we can reliably assess the impact of COVID-19 on U.S. death-penalty sentencing and execution trends.

Innocence Top

The inadequacy of judicial review to protect the innocent from wrongful capital convictions stood out boldly in 2020, as six innocent men were exonerated after decades on death row, two likely innocent men were executed, and several others were granted retrials or entered a plea to crimes they did not commit to gain their freedom. Official misconduct continued to be the leading cause of wrongful capital convictions, typically occurring alongside false accusation, junk science, eyewitness misidentification, and ineffective representation.

2020 Exonerations

The six exonerations in 2020 brought the number of documented death-row exonerations in the United States since 1973 up to 173 individuals.

Paul Browning

On January 24, 2020, months after his release from prison, the Nevada Supreme Court affirmed the decision of a Las Vegas trial court that had dismissed all charges against former death-row prisoner Paul Browning, formally completing his exoneration. Browning’s case involved all of the leading causes of wrongful convictions: official misconduct, perjury, false forensic evidence, eyewitness misidentification, and inadequate representation. His trial attorney had been practicing criminal defense for less than a year and failed to interview the police who responded to the scene, examine the evidence against Browning, or investigate the crime. This was only worsened by the fact that police and prosecutors had withheld evidence of a bloody footprint found at the scene that did not match Browning’s shoes or foot size and had misrepresented other blood evidence in the case. The victim’s wife couldn’t identify Browning in a line-up and another white witness from the scene claimed that she thought all Black people looked alike, yet both were allowed to testify at trial that Browning was the killer.

Walter Ogrod (second from right) with his defense team

Philadelphia saw two new death-row exonerees this year, with the six total exonerations from that city since 1973 all involving official misconduct. In a dramatic virtual hearing held on June 5, a Pennsylvania judge agreed to overturn Walter Ogrod’s wrongful conviction and death sentence, reducing the charges to third-degree murder so he could be released on bail. The Philadelphia District Attorney’s office dropped all charges a few days later.

Ogrod had consistently maintained his innocence in the 1988 murder and alleged sexual assault of a four-year-old girl. His first trial ended in a mistrial when one of the 12 jurors who had voted to acquit changed his mind. Before his second trial, prosecutors engaged the assistance of a notorious jailhouse informant, who worked with another informant to fabricate a confession from Ogrod. That testimony, along with a false confession elicited after 14 hours of interrogation by homicide detectives who had coerced false confessions in several other cases, sent Ogrod to death row.

Ogrod’s exoneration efforts gained new momentum with the support of both the Philadelphia District Attorney’s office and Sharon Fahy, the mother of the murder victim. A review of Ogrod’s case by the DA’s Conviction Integrity Unit (CIU) concluded that the evidence used to send Ogrod to death row had been “false, unreliable and incomplete.” There had been no sexual assault and autopsy evidence showed that the murder had not been committed in the manner presented by the prosecution. Ogrod’s conviction, CIU Chief Patricia Cummings said, was a “gross miscarriage of justice,” marred by police and prosecutorial misconduct — including the presentation of junk science and false informant testimony, and withholding exculpatory evidence concerning the cause of the young girl’s death.

Kareem Johnson

Former Pennsylvania death-row prisoner Kareem Johnson was exonerated on July 1, 2020, thirteen years after being wrongfully convicted and sentenced to death by a Philadelphia jury. The prosecution, police, and a prosecution forensic analyst told the jury that Johnson had shot the victim, Walter Smith, at close range, based on a blood-splattered baseball cap that supposedly had been recovered at the murder scene and contained Johnson’s sweat. In fact, there was no blood on the hat recovered on the ground near the scene, nor did the initial DNA samples collected from the hat link the sweat to Johnson. Instead, the victim’s blood was on a different hat that the victim himself had been wearing when he was shot. When post-conviction counsel discovered this discrepancy, prosecutors claimed the error had been an accidental mix-up.

The Philadelphia DA’s office agreed in April 2015 that Johnson’s conviction should be overturned but stipulated that the reversal was based only “on ineffective assistance of counsel at the guilty-innocence phase of trial.” Johnson moved to bar his retrial on double jeopardy grounds. However, despite describing the prosecution’s behavior as “extremely negligent, perhaps even reckless,” the lower courts allowed the retrial to proceed. On May 19, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court reversed, finding that the misconduct — even if not deemed intentional — was so severe that retrying Johnson would violate his constitutional rights. All charges were formally dismissed on July 1.

Curtis Flowers

After six trials marred by prosecutorial misconduct and racial prejudice that drew a scathing rebuke from the U.S. Supreme Court, former Mississippi death-row prisoner Curtis Flowers was officially exonerated on September 4, 2020. Flowers, who is African American, was tried for capital murder six times by the same white prosecutor, Fifth Circuit Court District Attorney Doug Evans. Four of the trials resulted in convictions and death sentences imposed by all-white or nearly all-white juries, but each conviction was overturned for prosecutorial misconduct. Despite Evans’ relentless efforts to send Flowers to death row, the only direct evidence of guilt came from a jailhouse informant who claimed that Flowers had confessed to the murders. The informant later admitted to fabricating this confession.

The U.S. Supreme Court vacated Flowers’ sentence in 2019 based on Evans’ unconstitutional removal of Black jurors. Justice Brett Kavanaugh wrote that Evans’ “relentless, determined effort to rid the jury of black individuals strongly suggests that the State wanted to try Flowers before a jury with as few black jurors as possible, and ideally before an all-white jury.” Following the Supreme Court’s reversal, Evans expressed his intention to try Flowers for a seventh time. However, after a federal lawsuit was filed to prevent Evans from engaging in future acts of jury discrimination and Flowers’ defense team moved to remove his office from the case, Evans voluntarily withdrew from the case. Attorney General Lynn Fitch took over the prosecution, reviewed the case, and filed a motion to dismiss the charges against Flowers. The trial court granted the motion, leaving Flowers “finally free from the injustice that left [him] locked in a box for nearly 23 years.”

Robert DuBoise

Robert DuBoise was released from prison in Florida in August 2020 after new DNA evidence proved his innocence. DuBoise had been convicted of rape and capital murder based on junk-science bite-mark evidence and false testimony from a prison informant. The jury unanimously recommended that DuBoise be sentenced to life, but his trial judge, Henry Lee Coe III, overrode their recommendation and sentenced DuBoise to be executed in Florida’s electric chair. In February 1988, the Florida Supreme Court resentenced him to life in prison instead, ruling that the trial court should not have overridden the jury. At an evidentiary hearing in September 2020, all of DuBoise’s charges were formally dismissed, and DuBoise became Florida’s 30th death-row exoneree since 1973, the state with the most exonerations in the nation. The state has executed 99 prisoners during that period, or one exoneration for every 3.3 executions. Until 2016, Florida permitted trial judges to impose death sentences despite jury recommendations for life or based on non-unanimous jury votes for death. Including DuBoise’s case, in 22 of the 24 Florida exonerations for which the jury’s sentencing recommendation is known, the jury either recommended a life sentence or was not unanimous in recommending death.

Roderick Johnson was exonerated from Pennsylvania’s death row on December 1, becoming the third person exonerated in Pennsylvania this year, when the Pennsylvania Attorney General’s office declined to appeal a trial court order barring his reprosecution because of “egregious” prosecutorial misconduct. Johnson’s wrongful conviction was based on the testimony of a drug dealer and police informant who had repeatedly avoided prosecution by providing information to police in other cases. The trial prosecutor, then-Berks County District Attorney Mark Baldwin, suppressed five separate police reports that documented the witness’s criminality and the benefits he had received from police in exchange for his past cooperation. Judge Eleni Dimitriou Geishauser, who dismissed all charges against Johnson, wrote an opinion excoriating Baldwin for the “deliberate nature of his contemptuous behavior,” which she said was “evident in the fact that he blatantly lied about his knowledge of the reports directly to the court.”

Executed But Likely Innocent

Three of the 17 people executed in 2020 raised significant claims of innocence. Their cases highlighted the danger of junk science, an ongoing pattern of denial of potentially exculpatory DNA testing, and the racial disparities that are present in innocence cases.

Donnie Lance

Donnie Lance was sentenced to death for the murder of his ex-wife and her boyfriend. Lance maintained his innocence and sought DNA testing that he said would exonerate him. His children, who were also the children of the victim, joined in asking the state to grant the request. The prosecutors opposed DNA testing and the Georgia courts denied Lance’s request. “It’s just mind-boggling that we have this evidence, but the state of Georgia is not willing to truly try to find out if this man is innocent before they kill him,” Lance’s son, Jessie, said.

Former Georgia Governor Roy Barnes said that during his tenure, he instructed the Board of Pardons and Paroles to permit requests for DNA testing. “I was not going to take the risk of an innocent man being executed,” he said. “Even one mistake in a death case cannot be tolerated. There have just been too many cases where years later DNA exonerated someone.” Lance was the third consecutive Georgia prisoner executed after being denied potentially exculpatory DNA testing.

Nathaniel Woods

Alabama’s execution of Nathaniel Woods featured several hallmarks of wrongful conviction: official misconduct, coerced informant testimony, and racial discrimination. Woods was sentenced to death for the killings of three police officers in June 2004. Prosecutors acknowledge that Woods’ co-defendant, Kerry Spencer, shot the officers in an incident in a drug house. Spencer confessed to having shot the officers, but says he did so in self-defense after they had beaten Woods during a shakedown and pointed a gun at him. Knowing he was not the shooter, prosecutors offered Woods a plea deal for 20 – 25 years, but his trial lawyer advised him not to take it, misinforming him that he could not be convicted of capital murder as an accomplice.

After Woods, who is Black, turned down the plea deal, prosecutors claimed at trial that he had been the mastermind of a plan to kill the three white officers because he supposedly hated police. In support of that new theory, they presented testimony from Woods’ girlfriend that he had made comments about his hatred of police. But even before the trial, she recanted. “I made that up. I told y’all what you wanted to hear,” she said at a pretrial hearing.

Woods’ appeal alleged that police threatened to charge her with parole violations if she did not testify. At trial, the court refused to allow the defense to present evidence of police misconduct.

Spencer called Woods “100 percent innocent.” “Nate ain’t done nothing,” he said. “All he did that day was get beat up and he ran.”

Walter Barton

Walter Barton’s conviction in Missouri relied on junk science testimony that asserted small blood stains on Barton’s clothes were “impact stains” from “high velocity” blood spatter, which the prosecution argued occurred while Barton was purportedly stabbing 81-year-old Gladys Kuehler. However, a 2015 analysis by crime scene analyst Lawrence Renner concluded that the bloodstains on Barton’s clothes were actually “transfer stains,” likely caused by contact with other bloodstains. Kuehler had been stabbed 50 times, and Renner said that the perpetrator of such a grizzly murder would have been covered in the victim’s blood. Barton was one of three people, along with a neighbor and Kuehler’s granddaughter, Debbie Selvidge, who discovered her body. He says he pulled Selvidge away from Kuehler’s body, getting droplets of Kuehler’s blood on his clothes. Prior to the execution, three jurors who had voted to convict Barton signed affidavits saying that the new analysis of evidence from the case would have affected their decision to convict him.

Growing National Attention to Issues of Innocence, Race

As issues of innocence and racial discrimination come to the forefront of the national consciousness, multiple death-row prisoners’ cases made mainstream news.

Pervis Payne

As the Black Lives Matter movement reignited conversations about institutional racism in the United States over the summer, a growing coalition of state legislators, legal associations, faith leaders, and community groups in Memphis called for the courts to permit DNA testing that could potentially exonerate Pervis Payne, a Black death-row prisoner who may be both innocent and intellectually disabled and who has been denied access to the courts to review those claims. At Payne’s racially charged trial, prosecutors characterized Payne — a pastor’s son who had no prior record, no history of drug use, and no history of violence — as a sexually predatory Black man, high on drugs, who attacked a white woman. Without evidence, they asserted that Payne had sexually assaulted Charisse Christopher, showing the jury a bloody tampon that they asserted he had pulled from her body. However, the tampon did not appear in any of the police photos or video taken at the crime scene. Following this wide-spread support from the African-American community and citing the coronavirus pandemic, Governor Bill Lee granted a temporary reprieve to Payne, halting his December 3, 2020 execution until at least April 9, 2021.

Julius Jones

The innocence case of Oklahoma death-row prisoner Julius Jones, a Black high school sports star and honors student sentenced to death in 1999 for the murder of a prominent white businessman, received broad public support in 2020 from high-profile celebrities, athletes, and racial justice organizations. At the start of the 2020 National Football League season, Dallas Cowboys quarterback Dak Prescott and Cleveland Browns quarterback Baker Mayfield, who played collegiate football at the University of Oklahoma, raised public awareness about Jones’ case, writing letters to Governor Kevin Stitt urging him to grant clemency and wearing decals on their helmets supporting Jones. The quarterbacks joined NBA stars Blake Griffin, Trae Young, and Russell Westbrook in supporting Jones’ clemency petition, which was submitted to the Pardon and Parole Board in October 2019. By mid-2020, an online petition calling for clemency had gained nearly 6 million signatures, and rap superstar Common and reality TV celebrity Kim Kardashian West called attention to his case. Black Lives Matter — OKC included his commutation as one of its demands for local criminal legal system reforms.

Junk Science Implicated in Wrongful Convictions in 2020

Three of the six 2020 death-row exonerees’ cases were plagued by junk science, but junk science played a role in several other capital cases as well.

Peter Romans, with his family

In October, a three-judge panel in Madison County, Ohio acquitted Peter Romans, who had been charged with capital murder for allegedly starting a fire to burn down his house with his wife and children inside in 2008. While prosecutors theorized that Romans poured gasoline on the driver’s side of his car and intentionally set it ablaze, the defense presented expert testimony that the fire had instead been caused by a faulty cruise-control deactivation switch in his Ford Expedition. At the time of the fire, Ford had issued a recall for the faulty switch because it had been implicated in spontaneous vehicle fires, some of which occurred when the engine was off, but Romans’ SUV had not been repaired after the recall. Because the car had sustained so much damage in the 2008 fire, investigators didn’t pronounce it a case of arson for more than a year. The deaths were not declared homicides until 2011, three years after the fire. Romans’ indictment for capital murder didn’t occur until a full decade after the tragedy. His defense lawyer asked, “Why now? … What evidence has changed after 11 years?” Romans’ case is one of many involving junk arson science, and the National Academies of Science have warned since 2009 that “many of the rules of thumb that are typically assumed to indicate that an accelerant was used [to start a fire] … have been shown not to be true.”

The Mississippi Supreme Court granted a new trial to death-row prisoner Eddie Lee Howard, Jr. in August 2020, based on scientifically invalid bitemark evidence and new DNA evidence. First convicted in 1994, Howard’s death sentence was overturned, but he was sentenced to death once again in 1997 in a retrial featuring testimony from forensic odontologist Dr. Michael West. West asserted that Howard was the source of bite marks he claimed to have found on the victim’s body during a post-autopsy, yet the initial autopsy by Dr. Steven Hayne had noted no such marks. Bitemark-identification claims such as those made by West were the subject of blistering criticism by the National Academies of Science in a landmark 2009 report, exposing the field of forensic odontology as lacking any “evidence of an existing scientific basis for identifying an individual to the exclusion of all others.”

“Mr. Howard has been in prison for almost thirty years, almost all of that time on death row, slated to be executed,” Mississippi Innocence Project director Tucker Carrington said in a statement. “It’s now time to bring this case to an end — and to close another door on a disastrous era of injustice in this state.”

Prosecutorial Misconduct and Innocence

Johnny Lee Gates

Johnny Lee Gates was freed from death row in May 2020, 43 years after being sentenced to death in Georgia for a murder he has steadfastly maintained he did not commit. Gates entered a “Alford plea” on charges of manslaughter and armed robbery, meaning he did not admit guilt but also conceded that prosecutors had enough evidence to originally convict him. After giving a confession his lawyers say was coerced, the intellectually disabled Gates has maintained his innocence. During the appeals process, Gates’ defense attorneys obtained jury selection notes from the trial prosecutors that demonstrated how they systematically excluded Black prospective jurors to empanel all-white or nearly all-white juries in numerous capital trials. New evidence of neckties and a bathrobe belt used to bind the victim were even unearthed in 2015 by two Innocence Project interns after the prosecution had falsely asserted that no physical evidence was ever discovered at the scene of the crime.

Data from recent death-row exonerations highlight a disturbing pattern of prosecutorial misconduct, including the use or threatened use of the death penalty to secure false confessions from or false testimony again innocent defendants. DPIC’s October 2020 report, Use or Threat of Death Penalty Implicated in 19 Exoneration Cases in 2019, found that prosecutors or police officers had used the threat of death penalty as a coercive tool that led to or extended the wrongful convictions of more than 13% of the 143 exonerations reported in the National Registry of Exonerations annual review of the previous year’s cases. Those 19 individuals alone lost a combined 500 years of freedom to wrongful incarceration. As DPIC Executive Director Robert Dunham explained, “The data suggest that the misuse of the death penalty as a coercive interrogation and plea-bargaining tool poses a far greater threat to the fair administration of the criminal laws than we had previously imagined.”

Clemency Top

Jimmy Meders

Two states granted clemency to death-row prisoners in 2020.

In January, the Georgia Board of Pardons and Paroles granted clemency to death-row prisoner Jimmy Meders, just six hours before his scheduled execution, commuting his death sentence to life without the possibility of parole. The Board issued its decision after receiving affidavits from every living member of the jury from Meders’ 1989 trial, all stating that they would have imposed a life sentence without parole instead of the death penalty if they had been provided that sentencing option at the time of trial. Meders is the 10th death-row prisoner granted clemency in Georgia and the 291st in the U.S. since 1976. Meders’ case was the first time the Board had granted clemency to a death-row prisoner since the state legislature enacted a new law in 2015 requiring the board to provide an explanation for its decision whenever it commutes a death sentence, but not when it rejects a clemency application.

Following the abolition of the death penalty in Colorado in March, Governor Jared Polis commuted the sentences of the state’s three remaining death-row prisoners to life imprisonment without the possibility of parole. In a statement issued at the time of the commutations, Polis said that he removed Nathan Dunlap, Sir Mario Owens, and Robert Ray from death row to reflect the reality that “the death penalty cannot be, and never has been, administered equitably in the State of Colorado.”

Problematic Executions Top

The executions in 2020 continued to raise questions concerning the apparent unwillingness of state and federal prosecutors and the courts to limit capital punishment to the most serious murders and the most culpable defendants. As in recent years, those executed in 2020 disproportionately reflected the most vulnerable or impaired prisoners, rather than the most culpable ones. All but one prisoner executed in 2020 had evidence of one or more of the following significant impairments: serious mental illness (8); brain injury, developmental brain damage, or an IQ in the intellectually disabled range (6); chronic serious childhood trauma, neglect, and/or abuse (14). In addition, three of the seventeen executed prisoners were teenagers and four were under 21 years old at the time of their offenses, placing them in a category that neuroscience research has shown is materially indistinguishable in brain development and executive functioning from juvenile offenders who are exempt from execution.

The year’s executions also highlighted numerous systemic problems in the application of the death penalty, including racial bias, the violation of Native American tribal sovereignty, disregarding the wishes of victims’ family members, ineffective representation, and inadequate appellate review.

Donnie Lance maintained his innocence in the killing of his ex-wife, Joy Lance. His adult children, who were also the children of the victim, supported his request for DNA testing and asked the state to grant clemency. In 2019, three U.S. Supreme Court justices dissented from the Court’s refusal to review Lance’s claim of ineffective assistance of counsel. His trial counsel failed to present any mitigating evidence, even though Lance had brain damage from repeated head traumas. Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote that allowing the execution “permits an egregious breakdown of basic procedural safeguards to go unremedied.”

Lance’s appellate lawyers also argued that the capital charges against him were the product of improprieties in the legal process. In a motion filed in the Georgia Supreme Court, he presented evidence that prosecutors had illegally corrupted the indictment process by stacking the jury with hand-selected friends and allies, rather than randomly selecting members as required by law.

Abel Ochoa

Abel Ochoa, a Texas prisoner with brain damage and mental illness resulting from his drug addiction, was executed on February 6 after courts declined to hear his claim that the state unconstitutionally interfered in the clemency process by preventing him from submitting evidence in support of his clemency application.

Nicholas Sutton

Nicholas Sutton was executed in Tennessee on February 20, 2020. Governor Bill Lee declined to grant clemency, despite affidavits of support from seven Tennessee correctional officials, members of the victims’ families, and five of the jurors in Sutton’s case. “Five Tennesseans, including three prison staff members, owe their lives to him,” the petition said. The petition supported that claim with statements from two corrections officers who said that Sutton had saved their lives, and an earlier statement by a since-deceased sheriff’s deputy that described how Sutton had protected him from an attack by another prisoner.

The clemency petition documented Sutton’s transformation from a man who experienced extreme abuse and trauma during childhood that impaired his reasoning and judgment, to one who had experienced remarkable growth during his time in prison. Former corrections officer Tony Eden wrote, “Nick Sutton is a prime example of a person’s ability to change and that those convicted of murder can be rehabilitated. If Nick Sutton was released tomorrow, I would welcome him into my home and invite him to be my neighbor.”

Nathaniel Woods’ racially charged Alabama convictions and death sentences were tainted by evidence of police corruption, intimidation of witnesses, and inadequate representation. Prosecutors acknowledged that Woods’ co-defendant, Kerry Spencer, shot three white police officers in an incident in a drug house on June 17, 2004. Spencer acknowledged that he alone had shot the officers but maintained that he did so in self-defense after they had beaten Woods during a shakedown and pointed a gun at him. It was undisputed that Woods was not the shooter, and the prosecution initially offered him a plea deal for 20 – 25 years in prison. However, he turned down the deal based on erroneous advice from his counsel that he could not be convicted of capital murder as an accomplice. After Woods, who is Black, turned down the offer, prosecutors changed their theory of the case to assert at trial that Woods supposedly hated police and had masterminded a plan to lure the officers to their deaths.

The first execution carried out after the COVID-19 pandemic reached the United States was that of Walter Barton in Missouri on May 19. Barton’s conviction relied on junk science contradicted by later expert analysis. Barton maintained his innocence in the murder of 81-year-old Gladys Kuehler. Repudiated blood spatter evidence and the testimony of a prison informant who had been convicted 29 times for fraud, forgery, and related offenses were the primary evidence against Barton. Prior to the execution, three jurors who had voted to convict Barton signed affidavits saying that the new analysis of evidence from the case would have affected their decision to convict him.

Billy Joe Wardlow

Billy Joe Wardlow was 18 years old when he killed 82-year-old Carl Cole. The troubled teen of a brutally abusive mother, Wardlow had attempted suicide three times between age 15 and 18. Weeks before the murder, he reportedly tried to drive a stolen truck off a bridge. He killed Cole during a botched attempt to steal Cole’s car so that Wardlow and his girlfriend could pursue their fantasy of running away from their abusive homes to start a new life in Montana.

Wardlow was sentenced to death based upon false but uncontested testimony by a criminal investigator for the Texas Special Prosecution Unit that he posed a continuing threat to society if the jury sentenced him to life because he would be housed in the general prison population, where his presence would put prison guards and others at risk. Wardlow challenged the state’s use of “future dangerousness” findings to impose the death penalty on defendants younger than age 21 at the time of their offense, arguing that such findings “are inherently unreliable” in light of the ongoing development of the adolescent brain. His claims were supported by neuroscience professionals including the American Academy of Pediatric Neuropsychology, the Center for Law, Brain and Behavior at Massachusetts General Hospital, and the Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine, as well eight leading experts in brain research and adolescent behavior.

Wardlow was executed on July 8. He was the fourth Texas prisoner executed since 2019 after false future-dangerousness testimony by Texas Special Prosecution Unit criminal investigators.

On July 14, Daniel Lewis Lee became the first person executed by the U.S. federal government in 17 years. The government proceeded with the execution under an artificially rushed timetable that prevented courts from conducting evidentiary hearings that were necessary to adjudicate a series of complex issues concerning the legality and constitutionality of the federal execution process. Lee’s execution was opposed by the victims’ family, the trial prosecutor, and the trial judge. The European Union and more than 1,000 faith leaders from a variety of religious backgrounds joined them in calling for clemency.

By carrying out the execution in the midst of a global pandemic, the government forced the victims’ family – including Earlene Peterson, the 81-year-old mother and grandmother of the victims – to choose between attending the execution and risking their health. The family filed suit to delay the execution until the pandemic was over, and a federal district court in Indiana issued an injunction against the execution. The Department of Justice successfully appealed the injunction, deriding the family’s lawsuit as “frivolous” and their fear of contracting the coronavirus as a mere travel inconvenience. Monica Veillette, a cousin and niece of the two victims, said the government’s conduct retraumatized her family. “Over and over it’s been said that it’s being done for my aunt and cousin, it’s being done for our family,” she said. “And in the end, they completely dismissed us.”

The execution itself was marked by chaos. A flurry of last-minute court rulings caused by the compressed execution schedule, including a district court injunction based upon the likely unconstitutionality of the federal execution protocol, pushed Lee’s execution past the midnight expiration of his notice of execution. In the predawn hours of the morning of July 14, the U.S. Supreme Court vacated the injunction and denied other applications to stay the execution. The Bureau of Prisons (BOP) began preparing Lee for execution around 4 a.m., strapping him to the gurney and reading him a new notice of execution. Notified by defense counsel that a stay of execution was still in effect from an Arkansas federal court ruling in December 2019, the BOP left Lee strapped to the execution gurney for nearly four hours while prosecutors filed motions in the federal appeals court to terminate the stay. The appeals court lifted the stay at 7:36 a.m. Without notifying defense counsel, BOP proceeded with the execution, even as multiple motions in his case were still pending. Lee was declared dead at 8:07 a.m.

Wesley Purkey

The scheduled July 15 execution of Wesley Purkey followed a similarly tumultuous path. Purkey’s lawyers argued that, because of the combined effects of schizophrenia, brain damage, and dementia, he had become mentally incompetent and was ineligible for execution. They sought a stay of execution so the district court could conduct a hearing to determine his competency. Around 2:45 a.m. on July 16, after the execution notice had expired, the Court voted 5 – 4 to permit the execution to proceed. Justice Sonia Sotomayor, joined by Justices Breyer, Ginsburg, and Kagan, authored a vigorous dissent sharply criticizing the Court’s “decision to shortcut judicial review and permit the execution of an individual who may well be incompetent.”

With motions still pending in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit, Purkey was executed at 8:19 a.m. His attorney, Rebecca Woodman, wrote, “We should expect more of our federal government than the rushed execution of a damaged and delusional old man. As the district court in Washington, D.C. quoted …, ‘the public interest has never been and could never be served by rushing to judgment at the expense of a condemned inmate’s constitutional rights.’ What happened today is truly abhorrent.”

Dustin Honken’s federal execution on July 17 marked the first time in the modern era of the death penalty that a prisoner was executed for a crime committed in a state that had abolished the death penalty. Honken was convicted of a 1993 murder in Iowa. He challenged informant testimony against him, saying that the informants had coordinated their testimony and prosecutors withheld evidence that could have been used to impeach their credibility.

Lezmond Mitchell

Lezmond Mitchell, a Navajo citizen, was executed on August 26 in a case that raised significant questions about the federal government’s respect for Native American tribal sovereignty. Mitchell was the first Native American executed by the federal government for a crime committed against a member of his own tribe on tribal lands. The Navajo Nation government has long opposed the death penalty as inconsistent with its culture and traditions and repeatedly objected to the U.S. Department of Justice’s decision to seek and carry out the death penalty for a crime committed on its lands. The National Congress of American Indians, thirteen tribal governments, and more than 230 members from more than 90 U.S. tribes and Alaska native communities joined Navajo Nation President Jonathan Nez in asking for clemency for Mitchell.

Mitchell alleged that his conviction and death sentence were the product of jurors’ anti-Native American bias. In support of that claim, he attempted to argue that prosecutors first discriminatorily excluded Native Americans from his jury and then presented racially derogatory arguments to the jury. However, the trial court barred his defense team from interviewing jurors to prove the claim, deferring to Arizona state law prohibiting post-trial contact with jurors. He sought to reopen his appeals after the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 2017 in Peña-Rodriguez v. Colorado that state rules against impeaching the jury’s verdict cannot be used to prevent a defendant from presenting juror testimony showing that the verdict was a product of racial bias. The lower federal courts ruled that they would not afford the protections of Peña-Rodriguez to cases like Mitchell’s that had completed their direct appeals before it was decided, and the Supreme Court refused to hear Mitchell’s appeal. He was executed without an opportunity to investigate and present his bias claim.

Keith Nelson was executed on August 28, 2020. Nelson experienced symptoms of psychosis and was very likely brain damaged before birth as a result of Fetal Alcohol Syndrome. Prior to the penalty phase of his trial, Nelson attempted suicide, but his trial attorneys did little to investigate his mental health. A petition to the U.S. Supreme Court described his upbringing as a “relentless barrage of trauma,” including physical and sexual abuse. His trial lawyers failed to present any evidence of his mental impairments to the jury during his trial. In February 2020, the U.S. Supreme Court declined to hear his case.

Portrait of William LeCroy

William LeCroy was executed on September 22. His attorney, who has underlying health conditions that place him at high risk for COVID-19, was unable to visit LeCroy to consult with him on critical pre-execution litigation and clemency efforts, and could not attend the execution. The U.S. Supreme Court denied his request for a stay because of this denial of access to counsel.

Christopher Vialva

Christopher Vialva and Brandon Bernard were the first teenage offenders put to death by the federal government in nearly 70 years. Vialva was 19 years old and Bernard 18 when they and three co-defendants, aged 15, 16, and 16, killed a Texas couple during a carjacking and robbery. In a commentary published before Vialva’s execution, Dr. Jason Chein, the director of the Temple University Brain Research and Imaging Center, wrote that while this was clearly an abhorrent act, “to make a final judgment about a person’s life based on a crime he committed as a teenager is to ignore what the last 20-plus years of research has taught us about the developing brains of teenagers and adolescents.” Vialva was executed on September 24 and Bernard on December 10.

Vialva argued that his trial had been marred by ineffective and conflicted counsel who failed to investigate the extensive evidence of his traumatic childhood and cognitive impairments. Unknown to Vialva, his lawyer was actively seeking employment with the U.S. Attorney’s Office that was prosecuting the case during the time he was representing Vialva. Vialva later discovered that his trial judge had presided over his trial and post-conviction proceedings while battling uncontrolled alcoholism and was reportedly intoxicated while conducting his judicial duties. The judge eventually resigned under pressure after the Judicial Council of the Fifth Circuit imposed “severe sanctions” and ordered him to desist from continuing misconduct.

Brandon Bernard

Bernard’s post-conviction lawyers argued that he was less culpable than younger co-defendants who had received lesser sentences, and that prosecutors presented false junk-science testimony to argue he would pose a future danger in prison while suppressing evidence that their own expert believed he was less culpable than others involved in the murders. Bernard had an exemplary behavior record in his more than 20 years in prison. Because of evidence the defense failed to present and that the prosecution misrepresented, Bernard’s age, and his maturation in prison, a majority of the surviving jurors who sentenced Bernard to death either affirmatively supported his clemency efforts or did not oppose resentencing him to life. The federal prosecutor who defended his death sentence on appeal also urged President Trump to commute Bernard’s sentence.

Nonetheless, the Supreme Court refused to hear his case and he was executed without a ruling on his clemency petition. In dissent, Justice Sotomayor wrote: “Today, the Court allows the Federal Government to execute Brandon Bernard, despite Bernard’s troubling allegations that the Government secured his death sentence by withholding exculpatory evidence and knowingly eliciting false testimony against him. Bernard has never had the opportunity to test the merits of those claims in court. Now he never will.”

Orlando Hall was executed November 19, despite evidence that his conviction and death sentence were the unconstitutional product of systemic racial discrimination in the application of the federal death penalty in Texas and case-specific discrimination in the selection of jurors in his case. He presented data showing that, for federal defendants in Texas, a death verdict was nearly sixteen times more likely to be rendered in a case with a Black defendant than a non-Black defendant. Hall, who is Black, was convicted by an all-white jury, and the prosecutor who conducted jury selection in his case has twice been found to have engaged in racially biased jury selection in other cases. Hall was one of only two people executed in 2020 for the murder of a Black victim.

Alfred Bourgeois was executed on December 11, despite having an IQ in the clinically accepted range for intellectual disability. His lawyers argued that his death sentence violated the U.S. Supreme Court’s 2002 ruling Atkins v. Virginia and that his execution would violate the proscription in the Federal Death Penalty Act that “[a] sentence of death shall not be carried out upon a person who is mentally retarded.” No federal court reviewed his claims using medically appropriate definitions of intellectual disability.

New Sentences Continue to Highlight Systemic Death Penalty Flaws Top

Because of the pandemic, there were significantly fewer capital trials in 2020, and they disproportionately involved proceedings in which defendants waived critical procedural rights. Trials posed health risks not only to jurors and court personnel, but to defense and prosecution lawyers and investigators, witnesses, mental health experts, and their families. Attitudes towards the pandemic affected which jurors appeared for service and, with the racially imbalanced health impact of COVID-19, threatened to make capital juries even less representative of the community. The impact of COVID-19 health risks on the thoroughness and quality of capital defense representation remains to be seen. In a year with very few death sentences due to a global pandemic, it is already evident that a significant number of the death sentences imposed in 2020 paint a troubling picture of the legal process.

More than 20% of the new death sentences were the product of proceedings in which defendants were not afforded key procedural protections. Three of the eighteen people sentenced to death in 2020 waived their rights to a jury trial and to have jurors determine their fate, and a fourth represented himself from arrest through trial. In Florida, co-defendants Jesse Bell and Barry Noetzel both pled guilty and waived their rights to counsel, a trial, and a sentencing hearing. Each represented himself in the courtroom and each was sentenced to death by a trial judge. At the beginning of Bell’s penalty phase, the court offered him stand-by counsel. Bell accepted this offer, and then was provided a stand-by lawyer who did not meet Florida’s requirements for providing representation in a death-penalty case.

In Ohio, a three-judge panel sentenced Joel Drain to death. Drain had waived his right to a jury trial and sentence, presented no guilt defense, and refused to present mitigating evidence in the penalty-phase of his trial.

In California, a fourth defendant, Israel Ramirez Guardado, represented himself from arrest through trial, during which he continually maintained his innocence. In his closing statement, he told the jury, “It is totally up to you guys. Whatever [you] think I should get, I’m fine with it.”

Other defendants who were sentenced to death also proclaimed their innocence. In California, defendant Charles Merritt’s lawyer said that there was “not a shred” of evidence that Merritt was guilty. Even the prosecutor and judge admitted that the case against Merritt was constructed on circumstantial evidence. In Florida, defendant Mark Sievers told the court before sentencing: “Although a jury found me guilty, I’m innocent of all charges as I have maintained since the day this crime took place.”

Two of the defendants sentenced to death had documented histories of mental illness or chronically traumatic childhoods. In Florida, defendant Marlin Joseph was sentenced to death after his case bounced between mental-health and criminal court addressing issues of his competency to stand trial. Texas defendant Brandon McCall’s lawyers unsuccessfully pleaded for mercy, asking the jury: “If you grew up in a car and had to shower with a hose behind a church would you be the person you are today?” Six months before McCall’s crime, he had been hospitalized for suicidal behavior.