The U.S. Supreme Court has said the death penalty must be reserved for the worst of the worst murders and be imposed only on the worst of the worst offenders. But what of an accomplice to a felony in which someone was killed but the accomplice neither committed the killing nor intended that a killing would take place? Those co-defendants are not even the worst of the worst participants in the offense for which they are charged. Yet, as the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) reported on July 11, 2019, 27 states permit the use of the death penalty against non-triggermen.

In When the State Kills Those Who Didn’t Kill, Ashoka Mukpo explores the phenomenon of death sentences for people who did not kill a victim. Mukpo explains that felony murder laws “make[] all participants in a major felony liable for any deaths that happen while they’re carrying out their crime, even if they didn’t set out to kill anyone or even play a direct role in the death itself.” Felony-murder laws, the article suggests, interact with other flaws in the administration of capital punishment to compound systemic problems of arbitrariness and prosecutorial misconduct.

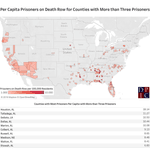

Mukpo looks at the issue through the lens of the case of Charles Burton, who was sentenced to death in Talladega County, Alabama for his role in a robbery of an Auto Zone store in which a co-perpetrator shot a customer to death while Burton was outside in the parking lot waiting for the others to return to the getaway car. Historically, Talladega County is an outlier in its aggressive pursuit of the death penalty. It has Alabama’s second-highest death-sentencing rate and, according to a DPIC analysis of county death rows, has the second highest number of death-row prisoners per capita among all U.S. counties with three or more prisoners on death row. Burton is the only one of the six robbers to be facing execution.

Burton was sentenced to die after a sixteen-year old witness whom the prosecution had threatened with the death penalty testified that Burton had told the group “if anybody needed to be hurt, let him do it.” The language was spoon-fed to the witness through leading questions by the prosecutor. The shooter, Derrick DeBruce also was sentenced to death, but his death sentence was later overturned following the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Atkins v. Virginia barring the death penalty against people with intellectual disability.

Numerous men and women have been convicted and sentenced to death under felony-murder laws since the death penalty was reinstated in the U.S. in the 1970s. At least 11 people whom prosecutors admit had no involvement in the killing itself have been executed. Two U.S. Supreme Court decisions address the constitutionality of using felony murder laws to sentence a defendant to death, but critics say the cases have produced a complex and muddled set of standards.

In 1982, the Court overturned the death sentence imposed on Earl Enmund, the getaway driver in a robbery in which two accomplices killed a Florida couple. In Enmund v. Florida, the Court found his death sentence unconstitutionally disproportionate because he was a minor participant in the felony and “did not kill, attempt to kill, or intend that a killing take place.” Five years later, the Court upheld the death sentences of two brothers who had helped their father escape from prison and carjack a family. Their father killed the family while the two sons were fetching water. In Tison v. Arizona, the Court ruled that the sons’ death sentences did not violate the constitution because each had played a “major” role in the carjacking and prison escape, and, although they neither killed nor intended that a killing take place, their conduct exhibited “reckless disregard for human life.” Eight states, including California, Florida, and Texas — the nation’s three largest state death rows — use the standard established in Tison in their felony murder laws.

Burton’s attorney, Matt Schulz, said, “Mr. Burton admits he is not a saint. But … he did not kill anyone during the commission of this crime, and has never killed anyone. He is not a murderer, and did not promote or encourage DeBruce to pull the trigger.” That Burton faces execution, the article says, shows that the death penalty is not properly applied. “The fact that we have people who are being sent to death for felony murder when they didn’t actually kill, and in some cases where they didn’t even intend to kill, is a sign that we don’t have any claim that we’re applying the death penalty to the worst of the worst,” said Cassandra Stubbs, director of the ACLU Capital Punishment Project.

Ashoka Mukpo, When the State Kills Those Who Didn’t Kill, ACLU, July 11, 2019