DPIC Summary

Executing the Will of the Voters?: A roadmap to mend or end the California legislature’s multi-billion dollar death penalty debacle

by Judge Arthur L. Alarcon & Paula M. Mitchell

published in 44 Loyola of Los Angeles Law Review S41, Special Issue (2011)

Read the entire article.

“Since reinstating the death penalty in 1978, California taxpayers have spent roughly $4 billion to fund a dysfunctional death penalty system that has carried out no more than 13 executions.”

UPDATE: Judge Alarcon and Prof. Mitchell issued an updated version of their article on the costs of the death penalty in California. Their abstract states:

In a 2011 study, the authors examined the history of California’s death penalty system to inform voters of the reasons for its extraordinary delays. There, they set forth suggestions that could be adopted by the legislature or through the initiative process that would reduce delays in executing death-penalty judgments. The study revealed that, since 1978, California’s current system has cost the state’s taxpayers $4 billion more than a system that has life in prison without the possibility of parole (‘LWOP’) as its most severe penalty. In this article, the authors update voters on the findings presented in their 2011 study. Recent studies reveal that if the current system is maintained, Californians will spend an additional $5 billion to $7 billion over the cost of LWOP to fund the broken system between now and 2050. In that time, roughly 740 more inmates will be added to death row, an additional fourteen executions will be carried out, and more than five hundred death-row inmates will die of old age or other causes before the state executes them. Proposition 34, on the November 2012 ballot, will give voters the opportunity to determine whether they wish to retain the present broken death-penalty system — despite its cost and ineffectiveness — or whether the appropriate punishment for murder with special circumstances should be life in prison without the possibility of parole.

The new article is: Judge Arthur L. Alarcón and Paula M. Mitchell, Costs of Capital Punishment in California: Will Voters Choose Reform this November?, 46 Loy. L.A. L. Rev. S1 (2012). It is available in full text at http://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/llr/vol46/iss0/1.

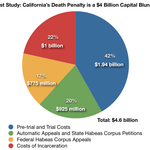

Cost Study: California’s Death Penalty is a $4 Billion Capital Blunder

The authors concluded that the cost of the death penalty in California has been over $4 billion since 1978.

Breakdown of Costs in California’s Death Penalty System

| Pre-trial and Trial Costs | $1.94 billion |

| Automatic Appeals and State Habeas Corpus Petitions | $0.925 billion |

| Federal Habeas Corpus Appeals | $0.775 billion |

| Costs of Incarceration | $1 billion |

| TOTAL | $4.6 billion |

Pre-Trial and Trial Costs: $1.94 billion

1,940 capital trials x $1 million per trial = $1.94 billion

- California has conducted approximately 1,940 capital trials since 1978

- Capital trials cost on average an additional $1 million more than non-capital cases

- Capital cases often cost 10 to 20 times more than murder trials that don’t involve the death penalty

- Additional costs are incurred from a multitude of factors: two attorneys per side (rather than one), multiple investigators, multiple experts in the penalty phase of the trial, extended jury selection process, the additional penalty phase, and a longer guilt phase.

Automatic Appeals and State Habeas Corpus Petitions: $925 million

Estimated $50 million per year average cost 1999 – 2010 (12 years): $600 million

Estimated $25 million per year average cost 1985 – 1998 (13 years): $325 million

(Does not include estimated costs for any appeals filed before 1985)

- California Supreme Court

- 2009 capital case budget: $15,406,000

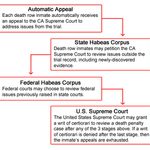

- The Supreme Court automatically considers all capital cases if a sentence of death was rendered

- Defendants have a constitutional right to representation on direct appeal, which is paid for by the state. The legislature has failed to provide adequate funding for the public agencies charged with defending capital defendants, thus the state has been forced to rely on appointing private lawyers. The average cost to represent a defendant in a case in which private lawyers are hired is between $200,000 and $300,000.

- Habeas Corpus Resource Center

- 2009 Budget: $13,857,000

- The Habeas Corpus Resource Center was created in 1998 by the California legislature.

- Attorneys from the HCRC are appointed by the California Supreme Court to represent indigent defendants in capital appeals.

- Office of the State Public Defender

- 2009 Budget: $12,000,000

- Originally designed to represent indigent defendants in all appeals, its mission has shifted to focus almost exclusively on capital appeals.

- Office of the California Attorney General

- 2010 budget: $115,200,000. About 15% allocated to prosecution of death penalty appeals: $17,300,000

Annual Costs of Automatic Appeals and State Habeas Corpus Petitions

| Agency | Most Recent Capital Appeals Budget |

| California Supreme Court | $15,406,000 |

| Habeas Corpus Resource Center | $13,857,000 |

| Office of the State Public Defender | $12,000,000 |

| Office of the California Attorney General | $17,300,000 |

| Total | $58,563,000 |

Federal Habeas Corpus Appeals: $775 million

350 CJA cases x $635,000 per case = $222,250,000

350 FPD CHU cases x $1.58 million per case = $553,000,000

- Two organizations provide the counsel for indigent defendants in capital cases:

- Federal Public Defender Capital Habeas Units (FPD CHU): roughly $1.58 million per case

- Criminal Justice Act (CJA) Panel of California: roughly $635,000 per case

- Nearly every condemned inmate seeks habeas corpus relief in federal court once the CA Supreme Court denies his or her constitutional claims.

- The costs of providing counsel to indigent defendants in federal court are borne by federal taxpayers, rather than the states.

- Federal courts granted relief (in the form of a new guilt trial or a new penalty trial) in roughly 70% of the cases that they have reviewed.

Costs of Incarceration: $1 billion since 1978

- An official within the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation estimated that housing death row inmates costs California an additional $90,000 annually per inmate. Accounting for inflation and the number of inmates on death row each year since 1978, this estimate would indicate that CA has spent an additional $1.02 billion in housing death row inmates since 1978.

- In 2010, California spent about $70 million incarcerating inmates on death row.

- California is currently planning the construction of a new Condemned Inmate Complex for the sole purpose of housing death row inmates.

- Originally projected to cost $220 million to construct, the total estimate for construction has ballooned to $395.5 million dollars.

- When coupled with the costs of activation, operation, and staffing costs for the first twenty years, the total cost for the new CIC will approach $1.7 billion in additional taxpayer dollars, according to the California State Auditor.

“The current backlog of death penalty cases is so severe that most of the 714 prisoners now on death row will wait well over 20 years before their cases are resolved. Many of these condemned inmates will thus languish on death row for decades, only to die of natural causes while still waiting for their cases to be resolved.”

Legislative History of the Death Penalty in California

Since 1978, all of the state’s death penalty legislation has been adopted through the passage of initiatives by a majority of voters. From 1978 to 2000, California voters have raised the number of death-eligible crimes from 12 to 39. The Briggs Initiative in 1978, which was proposed with the intent of creating the nation’s toughest death penalty, more than doubled the number of death-eligible crimes. Two propositions passed in 1990 added 5 death-eligible crimes and caused the death row population to balloon from 279 to 461 in just 4 years. Each time the death penalty was expanded in California, voters were told that the costs of expansion were “unknown” or “minor.”

“Considering that habeas corpus relief has been granted by federal courts in 70% of California’s death row inmates’ cases, a significant number of inmates who died while their petitions were pending may have had their convictions or death sentences set aside…but for the unconscionable delay in judicial review.”

Hazardous Conditions Ahead: Potential state and federal constitutional issues arising out of California’s current death penalty scheme

In analyzing the past death penalty initiatives enacted in California, the authors found several issues that could, if reviewed in state or federal court, lead a court to overturn California’s death penalty. These constitutional questions include:

- Is the current death penalty scheme what California voters intended?

- California courts recognize the general principle that, in determining the validity of voter initiatives, they must interpret and apply the electorate’s intent. If California’s death penalty system does not function in accordance with the electorate’s intent, it may not withstand judicial review. “The answer to whether voters intended to spend $4 billion on a system that has resulted in no more than 13 executions, certainly must be a resounding ‘No.’ ”

- In addition, initiatives are liable to challenge if the information provided to voters in the voting guide and other state resources was so inaccurate as to render voters incapable of making an informed decision. “It is clear from our research that, voting on the death penalty initiatives over a period of 32 years, California voters were not properly informed as to what the costs of expanding the imposition of capital punishment would be; nor were they informed of the fact that if the Legislature failed to provide proper funding to carry out those initiatives, it would result in the de facto repeal of the death penalty, resulting in what appears to be the weakest, least effective death penalty system in the nation.”

- Is the denial of due process ever cruel and unusual?

- State and federal courts, as well as the U.S. Supreme Court, have found that excessive delays in the appeals process may constitute a denial of due process. “The lengthy delays created by California’s defunct death penalty system visits another type of harm on another group of prisoners: those who have died after languishing on death row for many years while still awaiting review either of their automatic appeals or their potentially meritorious state or federal habeas corpus claims of constitutional violations.”

- No court has ruled on whether capital appeals, as currently implemented in California, deny a prisoner due process. Nor has any California case addressed the question of whether those prisoners who die on death row, waiting for their constitutional claims to be heard, have been subjected to cruel and unusual punishment.

- Is our view of the ‘worst of the worst’ overboard?

- The US Supreme Court in Furman v. Georgia (1972) held that the imposition of the death penalty was cruel and unusual punishment unless the discretion afforded to the sentencing body was narrowly tailored to fit the small number of crimes where the death penalty was “peculiarly appropriate.” California’s rather expansive definition of death-eligible crimes could run afoul of this requirement if challenged in court.

“Despite the consensus of state and federal officials supporting the call for Congress, the California Legislature, and the Governor to implement the necessary changes to provide for continuity of state and federal capital habeas counsel, no action has been taken to address this complete breakdown in the system. There have been no fewer than 13 bills introduced in the California Legislature since 2005 that have proposed various reforms to the administration of the death penalty in California, including moratoriums, capital trials, appeals, habeas proceedings, or housing of death row inmates. All have either died in committee or failed to pass.”

Remedies Revisited

The authors address and update the recommendations for reform made in Judge Alarcon’s 2007 article, “Remedies for California’s Death Row Deadlock,” published in the Southern California Law Review. These recommendations deal with shortcomings in the death penalty appeals process in California.

Remedies:

1. Automatic Review by the California Court of Appeal

- Members of the CA Supreme Court unanimously supported a measure to amend the CA Constitution to allow capital appeals (step 1, above) to be handled by the CA Court of Appeals. The Supreme Court would no longer be the sole body responsible for hearing capital appeals and would significantly reduce the backlog of cases before. The amendment never made it out of committee in the state Senate due to concerns over providing additional funding for counsel.

2. State Habeas Petitions filed first in the Trial Courts

- The California legislature could pass laws relieving the Supreme Court of its duty to review every petition for state habeas corpus relief (step 2, above) by requiring that original petitions for a writ of habeas corpus in capital cases be filed first in the court that entered the judgment of death. Although this change would not require a constitutional amendment, the two bills that attempted to make this change died in committee.

3. Increase Funding for Capital Appellate and Habeas Counsel

- The hourly rate of $145 for appellate and post conviction counsel remains far short of what can be considered reasonable compensation, discouraging the few qualified lawyers from accepting death penalty cases. In addition, if funds were provided for a consistent representative in the state and federal courts during habeas review (steps 2 – 3, above), the cases would spend less time shuffling between state and federal courts as additional claims are raised in federal court that must first be developed in state court.

Reform and Abolition in Other States

- New Jersey

- After a Death Penalty Study Commission found that the death penalty cost the state more than sentences of life without the possibility of parole, the legislature passed a law in 2007 abolishing capital punishment with the recommendation that “any cost savings…be used for benefits and services for survivors of victims of homicide.”

- New Mexico

- A 2007 court ruling stayed an execution because the state’s failure to provide adequate funds for defense counsel violated defendants’ 6th Amendment rights. After trial judges later ruled that prosecutors could not seek the death penalty unless further funds were allocated, a bill was introduced in the House Assembly to abolish the death penalty. Gov. Bill Richardson signed it into law in March 2009.

- Maryland

- A 2009 law restricted the state’s application of the death penalty to cases where biological evidence, such as DNA, videotaped evidence of a murder, or a videotaped confession is present. This new law is expected to save the state hundreds of millions of dollars over time, as well as drastically reduce the possibility of executing an innocent person.

- Illinois

- After Governor George Ryan decided that the death penalty in Illinois was “fraught with error” in 2000, a blanket commutation was issued to all 167 inmates left on death row in 2003. A moratorium on the death penalty persisted for ten years before the legislature approved a bill that abolished the death penalty in 2011.

“We hope that California voters, informed of what the death penalty actually costs them, will cast their informed votes in favor of a system that makes sense.”

Roadmap for Reform

Because the current system is the result of voter initiatives, any death penalty reforms in California must be implemented through voter initiatives. The authors suggest 5 propositions to reform or abolish capital punishment in California:

Propositions 1 and 2: Reform the Death Penalty but leave its current scope unchanged

1. Direct the legislature to fix the system by providing adequate funding for the appointment of qualified counsel and by creating an agency to ensure continuity of counsel through state and federal habeas appeals.

- This proposition would initially cost about $85 million per year, in addition to the amount currently spent on the death penalty. The change would come from increases to the budgets of the Office of the State Public Defender, Habeas Corpus Resource Center, Attorney General, and California Supreme Court.

2. Amend the California Constitution to allow automatic reviews to be undertaken by the California Court of Appeals rather than the CA Supreme Court. The Supreme Court could still have discretionary review in order to correct erroneous rulings or resolve conflicts among various districts

- This would result in a net savings of hundreds of millions of dollars over time due to condemned inmates spending less time on death row.

Proposition 3 and 4: Reform the Death Penalty by narrowing the number of death-eligible crimes

3. Reduce the number of death eligible crimes to 5 so that those sentenced to death truly represent the worst of the worst. (39 crimes are currently death-eligible.)

- This would create an immediate net savings of at least $55 million per year by reducing the number of death penalty trials by about half and reducing the size of death row.

4. Narrow the death penalty to cases in which the prosecution presents scientific or video evidence of guilt, or in which there is a recorded confession. This system is currently in place in Maryland.

- This would result in an immediate net savings of “tens of millions of dollars per year” by reducing the number of capital trials and appeals.

Proposition 5: Abolish the death penalty and replace it with a sentence of life without the possibility of parole

5. Assuming that the Governor would commute the sentences of those remaining on death row to life without parole.

- Assuming the Governor were to commute the sentences of those currently on death row, this option would result in an immediate savings of $170 million per year, with a savings of $5 billion over the next 20 years.