The Associated Press

By SHARON COHEN, DEBORAH HASTINGS, AP National Writers

Their time in prison surpassed 1,000 years, and all were wrongly convicted. Then they returned to lives that had passed them by.

An Associated Press examination of what happened to 110 inmates after their convictions were overturned by DNA tests found that, for many of the men, vindication brought neither a happy ending nor a happy beginning.

“It destroyed my family,” says Vincent Moto, unjustly convicted of rape and imprisoned for 10 1/2 years in Pennsylvania. “It cost me over $100,000 to get exonerated. That was my mom and dad’s money to retire. They’re struggling. I’m struggling.” Moto, a 39-year-old father of four, says his kids suffered psychologically and he still has nightmares of prison. He survives on odd jobs, welfare and food stamps. “I have to live with these scars all my life,” he says.

Richard Danziger is even less fortunate. Wrongly convicted of rape and sentenced to life, he suffered permanent brain damage when his head was bashed in by another inmate. Danziger was released in 2001 after he served 11 years in Texas. Now, at age 31, he lives with his sister, Barbara Oakley. “He basically gets up, watches TV, goes to the park, and that’s the extent of his day,” she says.

Lesly Jean, a 42-year-old former Marine imprisoned in North Carolina for a rape he did not commit, struggles to rebuild his life.

“You know that old saying, ‘When someone knocks you down, you need to get back up’? Well,” he says, “sometimes it’s not that simple to get back up.”

That’s especially true when the released men find themselves in a new world where they carry few up-to-date job skills, limited education, and heavy, if not bitter, hearts. For many, being set free doesn’t mean freedom.

In reviewing the cases of the 110, all men, the AP found:

- About half had no prior adult convictions, according to legal records and the inmates’ attorneys. While some were picked up for questioning because they were known to police, many had never been in trouble before.

- Eleven of the men served time on death row; two came within days of execution.

- Slightly more than a third have received compensation, mainly through state claims. Some have received settlements from civil lawsuits or special legislative bills. For others, claims or suits are pending; and some had lawsuits thrown out or haven’t decided

whether to seek money.

- The men averaged 10 1/2 years behind bars. The shortest wrongful incarceration was one year; the longest, 22 years. Altogether, the 110 men spent 1,149 years in prison.

- Their imprisonment came during critical wage-earning years when careers and families are built. The average age when they entered prison was 28. At release, it was 38.

- Their convictions follow certain patterns. Nearly two-thirds were convicted with mistaken testimony from victims and eyewitnesses. About 14 percent were imprisoned after mistakes or alleged misconduct by forensics experts. Nine were mentally retarded or borderline retarded and confessed, they said, after being tricked or coerced by authorities.

Finally freed — by determined lawyers or their own perseverance — the men were dumped back into society as abruptly as they were plucked out. Often, they were not entitled to the help, such as parole officers, given to those rightfully convicted.

“The people who come out of this are often very, very severely damaged human beings who often don’t ever fully recover,” says Rob Warden, executive director of Northwestern University School of Law’s Center on Wrongful Convictions. “Lightning strikes, they come out,” he says, “and they’re in bad, bad shape.”

They represent many walks of life — a homeless panhandler, a therapist, a junkie, a mushroom picker, a handyman, a crab fisherman — but almost all were working-class or poor.

Of the cases reviewed by the AP, about two-thirds involved black or Hispanic inmates, roughly reflecting state prison populations’ racial makeup.

“All of these people have a certain vulnerability. It may be race, class, mental health issues or personality problems,” says Peter Neufeld, who co-founded The Innocence Project with attorney Barry Scheck at the Cardozo School of Law in New York. About 60 percent of the men were helped by the 10-year-old legal assistance program, the rest by other groups or private lawyers. The first DNA releases came in 1989, according to the Innocence Project. “They sort of get caught in this Kafkaesque vortex,” Neufeld adds, “and the rest is history.”

Jeffrey Todd Pierce, for example. He had never been convicted of a crime when at age 24, he was found guilty of rape. Oklahoma City Police Department chemist Joyce Gilchrist testified that hair found at the scene matched Pierce’s, an analysis the FBI would conclude — 15 years later — was just plain wrong.

Pierce’s wife divorced him and his twin sons, now 16, grew up without him. After Pierce was released last year, he reunited with his family in Michigan, though he can’t bring himself to remarry.

“Prison made me look after myself, and I don’t want to commit to anything that can be taken away from me at an instant,” he says.

Or consider David Vasquez of Virginia. The 55-year-old man was mistakenly identified by a witness who said he was lurking outside the home of a woman later found raped and murdered. Vasquez, who is borderline retarded, confessed. Four years after his conviction, DNA testing identified the real killer, a serial rapist. “They destroyed his life and mine,” says Vasquez’s mother, Imelda Shapiro. “My life stopped in 1984. My son and I just sit in this house.” Shapiro begins to weep. “We can’t afford to go out, and I’m afraid to go out.” Her son bags groceries part time. “That’s about as much as he can handle,” she says. They live on his wages and $825 a month she secured through a special dispensation from the state.

For many exonerated men, re-entering society is baffling. There are so many changes — PIN codes, the Internet, wireless communication. “Everything was a lot faster than it was when I went in,” says Ronnie Bullock, 46, who spent a decade in an Illinois prison before being cleared of rape in 1994. “Pagers, cell phones, camcorders — even going to the grocery stores was different.”

So, too, was freedom.

After Kevin Green was released, he bought a cell phone and a pager so his family could keep track of him at every moment — just to allay their fears.

Charles Fain struggled to stop pacing five steps forward, then five steps back — the dimensions of his cell.

A team of AP reporters identified 110 cases through late May in which convictions were overturned because of DNA testing. Many other cases were pending. Most of the 110 men had been convicted of rape; 24 were found guilty of rape and murder, six of murder only. In criminal cases, the evidence most often tested for genetic identification is bodily fluids, which explains the high number of rape convictions overturned.

Legal experts differ on who these men represent.

Neufeld says they’re the tip of the iceberg.

From the late 1980s to the mid ’90s, before state and local police had their own labs for DNA testing, they sent the evidence to the FBI for analysis, he says. The results? The prime suspect turned out not to be a match in about 2,000 of 8,000 cases where there was enough material for testing, he says. Errors that lead to wrongful convictions also occur in cases where there’s no DNA to test, he says. “Is there any reason that a witness would be less likely to be mistaken in a robbery than a rape? “What this does tell you is we’re not talking about a handful of innocent people” in prison, he adds. “We’re clearly talking about thousands.”

Historically, of course, convictions have been overturned for many reasons, not just genetic testing; in fact, 11 people exonerated through the Innocence Project Northwest in Seattle had cases that did not turn on DNA results.

But John Wilson, who heads a state crime lab in Missouri and has testified as a DNA expert in criminal trials, doubts Neufeld’s point. He also says more widely available DNA testing has made wrongful convictions less likely in recent years. “The fact is, the majority of the time, the cops are right. It is the right guy,” Wilson says.

Some of the men whose cases the AP looked into had criminal pasts — no fewer than seven had prior convictions for sex crimes. In addition, 11 who were freed have been convicted of new crimes and nine of those have been sentenced to prison.

Kerry Kotler was exonerated of rape in 1992 in New York. Five years later, he was convicted of sexual assault. This time, DNA helped convict him.

Though genetic testing helped Albert Wesley Brown win release from an Oklahoma prison last year, he now admits he was guilty of the murder of a 67-year-old man. A crime-scene hair sample that had been used as evidence against him at trial wasn’t his, a DNA test later showed. But as prosecutors prepared to retry him without this mistaken evidence, he pleaded guilty. “I took him to the lake and drowned him and left him,” Brown said in court last month. The plea was in exchange for a sentence of time served, 18 years.

At the other end of the spectrum, some of the freed men have been remarkably successful.

Mark Bravo recently graduated with honors from a California law school and plans to start a foundation for people who get caught up in similar predicaments. Anthony Robinson just finished his first year as a law student in Texas. Timothy Durham helps run his family’s electronics store in Oklahoma. Edward Honaker has published two novels — both written in a Virginia prison. “The thing about it is, you can’t let your incarceration defeat you,” Honaker says. “And you can’t let it dictate the rest of your life.”

Death has claimed four of the men. Two died of cancer, one while in prison, and the other six months after his release.

Leonard Callace of New York died from a heroin overdose four years after he was freed. “When he got out, he was never able to put it in back of him,” says brother Pierre Callace.

Kenneth Waters enjoyed freedom for just a matter of months. His sister, Betty Anne, had only a high school equivalency diploma but put herself through law school to help win his release. In March 2001, after 18 years behind bars for a murder and armed robbery he hadn’t committed, Waters was released. He had contracted hepatitis C in prison, apparently from dental work. But that did not kill him.

Last September while taking a shortcut to his brother’s Massachusetts home, Waters fell from a 15-foot wall. He fractured his skull and died. “It’s hard,” Betty Anne Waters said at the time. “But we look at it as six months of freedom is better than 20 years in jail.”

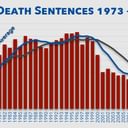

The pace of exonerations is quickening, keeping up with the availability of genetic testing. The Innocence Project reported 23 men were cleared last year by DNA, compared with six in 1992.

That increase has prompted much legislation giving inmates access to DNA testing to challenge their convictions. Twenty-five states now have such laws, all but two passed in the last three years, says Nina Morrison, the Innocence Project’s executive director.

But some new laws have restrictions that she considers unreasonable — such as a one-year period for inmates to seek DNA testing. That’s not enough time to assemble a case, she says.

Meanwhile, the number of inmates begging for genetic analysis grows. The Innocence Project says it has 4,000 cases at some stage of investigation.

The biggest problem, Neufeld says, is the race against time. In three-quarters of the Innocence Project’s cases, physical evidence such as hair or blood has been lost, misplaced or destroyed. During a criminal trial, the disappearance of evidence can mean acquittal. After conviction, it can mean losing all chances to prove one’s innocence.

When lawyers for Marvin Anderson wanted DNA analysis in 1993, they were told the evidence against him had been destroyed. But a swab containing genetic material was later found, taped to the inside of a lab technician’s notebook. It proved Anderson was not guilty — though not everyone was convinced. “Some people look at me like I’m guilty,” he says. “It’s hard finding a job. No one hires a person convicted of rape.”

Five years after his exoneration, Anderson is a trucker, scraping by on $200 to $400 a week. He faces the hardest task of the men able to work — earning a living wage.

Others say they cannot work because of post-traumatic stress syndrome, depression or physical handicaps.

Of 29 men who told the AP their income, the average weekly earnings were $438. If “all that’s on your resume is a blank, or state prison for the last 10, 15 years, there’s not exactly a bunch of people out there willing to hire you for other than minimum-wage jobs,” says Randy Schaffer, a Houston lawyer who represented three exonerated Texas men.

Steven Toney, a shuttle bus driver in Missouri, earns slightly more than minimum wage. He says he has struggled to get beyond menial jobs, but suspects his past has been held against him by prospective employers. “How many are going to come out and say, ‘I’m not hiring you because you were incarcerated’?” he asks. “But I don’t get the call.”

When Eduardo Velazquez looks for work, he carries a newspaper photo of himself taken the day of his release. After 13 years in a Massachusetts prison, he wants to prove he did nothing wrong. Still, says the 35-year-old man, no one will hire him.

Ronald Williamson came within five days of being executed for a murder and rape. After 11 years in prison, his bipolar disease degenerated to hearing voices and psychotic episodes. Today, the former minor-league ballplayer’s best chance for a job is an application he recently submitted to a cafeteria.

The families of these men also suffer.

Moto, the Pennsylvania man, recalls how his children would grab his legs as they ended their prison visits and plead to the guards, ’ ”Let my daddy go!“ ‘

Some families remain together, others are ripped apart.

Steve Linscott was convicted of murdering a young woman in suburban Chicago. Then a college Bible student managing a Christian halfway house with his wife, he told police about a strange dream he had, which in some ways was similar to the attack. The police considered it a confession. He ended up going to prison for more than three years. Linscott’s wife and children moved to southern Illinois, near the penitentiary, and waited for him. Now a therapist for emotionally disturbed children, he is working on his second master’s degree.

Ben Salazar was married to his childhood sweetheart, Christina. After four years of bringing their three children to a Texas prison visiting room, she couldn’t cope anymore. Salazar couldn’t stand to see her suffer. “I told her, ‘You do what you have to do.’ And she went on with her life. She filed for divorce. It was hard for me to say that … We grew up together.” Now 36, he is engaged to someone else.

Billy Wardell, 37, has a wife, a 2‑year-old daughter, a house and a job as a machinist — every single thing he dreamed of during 11 years in an Illinois prison. And yet something is missing. “There’s a big gap that makes me wonder … all the things I could have been and could have done,” he says. “Now there’s just a big piece of time that’s gone.”

Ronald Cotton Jr. faces the future by looking, unflinchingly, at his past. Jennifer Thompson is the rape victim whose mistaken identification put him in prison for 10 years. He has become her friend. Together, they give speeches. She lobbied to change laws so Cotton would be entitled to more than the $5,000 North Carolina originally offered as compensation. He received nearly $110,000. After becoming a free man in 1995, Cotton bought some land, got married, fathered a child and found work as a machine operator.

Still, he is haunted. “I know if it happened once,” he says, “it can happen again.”