Washington Post

December 1, 2000

By BROOKE A. MASTERS

Washington Post Staff Writer

“Did you stab a woman in Culpeper?” the state police detective asked.

The illiterate farm worker nodded.

“Was this woman white or black?”

“Black.”

A few questions later, Special Agent C. Reese Wilmore tried again. “Was she white or black?”

This time Earl Washington Jr. said, “White.” That answer launched the biggest mistake ever made by Virginia’s judicial system – and landed Washington on death row.

It wasn’t until Oct. 2 – 17 years after that police interview – that new DNA tests cleared Washington of the 1982 rape and slaying of Rebecca Lynn Williams. Recent interviews with Washington and Williams’s widower as well as dozens of police officers, judges and lawyers involved in the case turned up warnings that went unheeded along the way:

* Police and prosecutors moved forward with a case based almost entirely on a statement full of inconsistencies from an easily persuaded, somewhat childlike special-education dropout. Washington told investigators he “stuck her … once or twice,” but Williams bled to death from 38 stab wounds. He said she was alone. But there was a baby in a playpen and a toddler roaming through the small apartment. The defense made no mention of most of these inconsistencies during the trial.

* A judge ruled that the statement was admissible after hearing from a state mental health expert that a man with an IQ of 69 was competent to waive his rights to a lawyer during initial questioning – even though Washington still doesn’t know what the words “waive” and “provided” mean.

* No eyewitness or physical evidence put Washington at the scene. His blood type did not match a semen stain, and police instructed the state lab not to test key hair evidence. A judge rejected defense efforts to test the hair, and the defense lawyers never told the jury about the mismatched blood types.

* Six courts rejected the inmate’s claims of innocence, including a panel of federal judges who determined that Washington’s trial attorney had failed to meet minimal standards but upheld the conviction anyway. Virginia’s appeals judges, who overturn fewer death sentences than in any other state, ruled that Washington’s confession was properly admitted and the blood evidence was inconclusive.

* In 1993, DNA testing contradicted the prosecution’s theory and Washington’s confession that he alone attacked Williams. State officials reduced Washington’s sentence from death to life in prison but did not clear him.

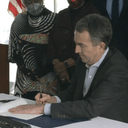

In October, Gov. James S. Gilmore III (R) pardoned Washington after more sophisticated genetic testing found no trace of him at the scene. But two families have been forever changed by Virginia’s unwillingness to reexamine the case. Washington, now 40, spent 17 1/2 years as a convicted murderer and came within five days of the electric chair. And Rebecca Williams’s killer remains unknown.

Although state officials have reopened the investigation, Williams’s widower, Clifford, feels betrayed by Culpeper authorities, who assured him that Washington was the right man and now won’t talk to him, he says.

“What do they have to hide? Why won’t they talk about it?” he asked in a recent interview. “I went for nearly 18 years believing Washington did it. Now I don’t know what to think.”

The mistakes in the Washington case have led to the first comprehensive examination of the state’s death penalty. The Virginia Supreme Court has proposed eliminating the legal rule that prevented Washington from seeking a new trial based on the first DNA test. Both the State Crime Commission and a bipartisan legislative committee are studying that issue as well as the quality of defense lawyers in capital cases and whether to help other convicts get genetic testing.

Still, determining what went wrong is difficult. The Washington Post tried to contact everyone involved in the Washington case. Several of them refused to comment. And nearly all the others defended their roles and insisted that the system worked. Only a single juror and a retired federal judge expressed misgivings about their actions.

The juror, Debera Ann Holmes, who, like Washington, is black, said she wasn’t convinced of his guilt when the trial ended: “With him being slow, he probably didn’t understand what the police were talking about … and if you’re a black man and they think you’re guilty, they’re going to make it so.”

But when most of the other jurors said they would stay all night to fight for a conviction, Holmes, now 41, capitulated. “I pray to God to forgive me for what I did,” said Holmes, one of only two black jurors. “It just hurts me.”

Seven years and five courts later, J. Dickson Phillips Jr. was also unhappy with what he saw. “My intuition was that there was something very, very wrong about the case in the first place,” said Phillips, who recently retired from the 4th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals. In 1991, that court sent Washington’s case back for more hearings – the only Virginia capital case to get that kind of scrutiny for 10 years. But after a lower court pronounced potentially exculpatory evidence inconclusive, Phillips said he felt legally bound to uphold the sentence.

“I wish I could have found a way to stop it.… I am delighted to hear about the pardon,” he said.

However, several investigators said they still believe Washington was involved.

“I feel as strongly about the case as I did back then,” said Fauquier County sheriff’s deputy Terry Schrum, who helped take Washington’s first statement.

Multiple Confessions

On June 4, 1982, Rebecca Williams stumbled to the front stoop of her Culpeper apartment, still conscious and begging for help. Her husband, who had been out with a friend, came home as his wife was waiting for the ambulance.

“I say ‘What happened?,’ and she says, ‘It was a black man with a beard,’ and she put her hands up like she was praying and kind of went to sleep,” Clifford Williams, now 41, recalled.

A neighbor reported seeing a lone black man jumping the fence behind the complex, and investigators took biological samples from five men. But the investigation seemed to run aground.

Nearly a year later, an illiterate farm laborer was arrested in neighboring Fauquiera. Angry with his brother, Earl Washington had broken into his elderly neighbor’s house to get a gun she kept there. When Hazel Weeks surprised him, he hit her with a chair.

Washington says he was so drunk that he doesn’t remember what happened next. But police notes and court records show he was immediately contrite about hurting Weeks. Investigators then asked about several other unsolved crimes in Fauquier, and Washington confessed each time.

Sgt. Alan Cubbage, a Warrenton investigator, remembers the call he got from Fauquier deputies that day about one of his cases. “They said, ‘You better get down here. We’ve already got a confession on your rape case,’ ” said Cubbage, 47. “It was almost like a big party. ‘Come on down, this guy is confessing to everything.’ ”

Schrum eventually brought up the unsolved slaying in Culpeper. Washington looked at the floor. So Schrum raised his voice – “EARL DID YOU KILL THAT GIRL IN CULPEPER?” the investigator’s notes say. “Earl sat there silent for about five seconds and then shook his head yes and started crying.” Schrum declined to discuss the interrogation in detail.

Investigators drove Washington all over Culpeper, trying to get him to show them where the killing took place. They had read him his Miranda warnings, and Washington waived his rights.

“I figured I didn’t need a lawyer [because I didn’t do it],” he said.

A mental health expert who examined Washington later found the inmate to be “extremely suggestible.… His innate orientation is to believe what others say.” Washington copes with an IQ that puts him in the bottom 2 percent of the population by following other people’s cues, University of New Mexico special education professor Ruth Luckasson wrote.

Wilmore, the Virginia State Police detective, and another investigator have died, but several others said they are still convinced of Washington’s involvement because he seemed to know so many details. According to a typed confession that Washington signed but could not read, he correctly said that the radio was on and the rape took place in a bedroom. Police also testified that when they showed Washington a shirt believed to have been left behind by the killer, he said it was his. And when they pointed out Williams’s apartment, Washington said he recognized it and had escaped over the fence.

“You would have to be associated with this crime in some fashion to know that,” said H. Lee Hart, now sheriff of Culpeper County.

Washington, who recanted his confession almost immediately, has a simple answer for where he got the information: “It’s the cops that tell me everything.”

If that’s true, said Culpeper Police Chief C.B. Jones, then Washington has to take the blame for what happened later.

“If he didn’t do it, then he did a miscarriage of justice. Even with his IQ, he knows better than that,” Jones said. “Some good people were involved in that case. They didn’t con him into confessing.”

Clifford Williams now wonders whether the authorities were as sure of their case as they claim. In the weeks after his wife’s death, Culpeper police found several hairs in the pocket of the shirt that was left behind, and they asked the lab to run comparisons with hair samples from five suspects.

But when Washington was arrested a year later, Investigator K.H. Buraker told the lab not to compare Washington’s hair with those in the shirt, according to lab records.

“You should run every piece of evidence and not pick and choose who you are going to pin it on,” Williams said. “If it had been tested back then, maybe then the investigation could have gone in another direction while the trail was still hot and not 18 years later.”

Buraker, now a captain with the Culpeper police, said he did not remember why he did not want the comparison done. The hairs from the shirt have disappeared.

Hiring a Lawyer

Although Washington was eligible for a court-appointed lawyer, his family and the local NAACP were so concerned that local attorneys would feel uncomfortable defending a black man on charges of raping and murdering a white woman that they hired a black lawyer from 35 miles away.

Neither John W. Scott Jr. nor his young associate, Gary A. Hicks, had ever handled a capital case. They immediately asked a judge to throw out the confession.

But prosecutor John C. Bennett argued that the police had acted properly, and the court ordered a mental health evaluation. Bennett, now in private practice, did not respond to seven phone messages and a letter sent to his office.

The state’s expert, psychologist Arthur Centor, concluded that Washington, despite his illiteracy and low IQ, “would have the capacity to understand the Miranda warnings … and make a knowing and intelligent waiver.”

Centor, now retired, stands by that evaluation. “He was competent to give the statement. Whether it was a valid statement is not something I’m competent to judge.… That’s for the jury,” he said.

The two Circuit Court judges who handled the case, F. Ward Harkrader Jr. and David Berry, declined to comment.

Scott said he did not ask for public money to hire an independent mental health expert to counter Centor because he thought the court would turn him down.

A year after Washington’s trial, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that a defendant in a capital case was entitled to his own mental health expert. Legal analysts said that an experienced death penalty lawyer would have known the issue was on appeal and would have tried to raise it.

“Using 20 – 20 hindsight, it was a mistake,” Scott said. “But under the circumstances, we did the best we could.”

Defense experts can be vital to point out the holes in a case that police and prosecutors may ignore or gloss over, analysts said. “Once police get the confession, the prosecutor is happy to say, ‘Oh, now I can get rid of this case,’ ” said University of Richmond law professor Ron Bacigal.

The three-day trial went badly for Washington. Scott failed to get the shirt evidence suppressed, even though Washington’s sister, Alfreda Pendleton, told the jury that she did all her brother’s laundry and had never seen the shirt. “The commonwealth said I was just up there saying things to protect Earl. I felt that, regardless of what I said, they had already decided the case, that he was guilty,” she said.

Washington did no better on the stand. He not only denied committing the offenses but also denied ever making the confessions. In the process, he looked like a liar, several jurors said.

Scott made no mention in his brief closing argument of the serious inconsistencies in Washington’s confession, and he said nothing about the lack of blood or other physical evidence. “We argued his basic IQ and education background.… There were an awful lot of things” to tell the jury, Scott said.

The jurors, though, remember the trial differently.

“I figured the defense was saying he was guilty, too, because they didn’t put on much of a case,” said juror Jacob Dodson, now 51. “The only thing they challenged was his [statement], but the judge ruled that admissible.”

Scott said he believes there was immense social pressure to send Washington to the electric chair. “I did a closing argument … and I heard people chewing gum. I heard newspapers rattling,” he said. “I have never had such a feeling that I was climbing this wall by myself.”

The jury deliberated for just 50 minutes before finding Washington guilty. It took them 90 minutes to recommend a death sentence.

“After what we heard, I didn’t think we had a choice,” said juror Frank Crescenti, now 76. “Thank goodness for DNA.”

Close to Execution

After the U.S. Supreme Court rejected Washington’s appeal in 1985, he came within five days of his execution date before a team of legal volunteers got a stay.

When Scott turned over his files to Robert Hall, the Fairfax County lawyer made a startling discovery: State laboratory tests had discovered semen that was blood type A on a bloody blanket from Rebecca Williams’s home.

Both Washington and Clifford Williams were blood type O.

“It jumps right out at you that we’re dealing with a third party who hasn’t been identified yet,” Hall said.

Yet Scott had told the jury nothing of the contradiction. He acknowledged in a 1989 affidavit that he had scanned the report but did not realize its significance. Prosecutor Bennett testified during an appeal that he knew the blood types didn’t match but believed the difference was “explainable” if the semen had been contaminated with Rebecca Williams’s vaginal fluid, which was blood type A.

When the case reached the 4th Circuit, Phillips and two other judges ordered new hearings on the blood evidence. But U.S. District Judge Claude M. Hilton subsequently ruled that the blanket results were inconclusive and would not have affected a jury. Hilton did not respond to requests for comment.

That ruling, Phillips said, put the 4th Circuit in a bind when it heard the case again. Although all three judges agreed that Scott’s failure to introduce the lab report was “incompetence,” Phillips and J. Harvie Wilkinson concluded that Hilton’s decision on the factual evidence was not “clearly erroneous.” Neither Wilkinson nor the dissenting judge, John Butzner, would comment.

“The lesson from that case is the absolute necessity that whenever people are charged with these heinous crimes, that they have really competent lawyers at the trial level,” Phillips said. “Once things go off track at the trial level, it is very difficult to undo the damage.”

Phillips also faults Virginia officials for defending Washington’s conviction so vigorously in spite of the serious errors. “I remember one of the state’s lawyers, how outraged he was that anyone could think that anything so terrible as the conviction of an innocent man could ever happen in the state of Virginia,” the judge said.

The state’s lawyers declined to comment. But Stephen Rosenthal, who oversaw the case as acting attorney general, said the office had done its job properly.

“Before any of the DNA testing, we didn’t believe there was enough evidence of innocence to offset our duty to protect a valid jury verdict,” he said. But, he added, “nobody on either side of this case has been very flexible, and perhaps that’s a lesson to be learned.”

Analysts said the judges are to be faulted as well. “The problem in Virginia is inadequate appellate review. If mistakes are made early on, they don’t get caught,” said Washington and Lee University law professor Roger D. Groot. “These cases just roll on through.”

Nationally, two-thirds of death sentences are overruled, compared with just 18 percent in Virginia, according to a study by Columbia University law school.

Washington was moving toward execution again when Rosenthal learned in 1993 that scientific advances had made it possible to do additional DNA testing. He ordered the lab work – even before the defense put in a request.

The results thrilled Washington’s defense team: The testing found genetic material that could not have come from Washington or Clifford Williams.

Washington’s attorneys were convinced he had been exonerated, as Rebecca Williams’s dying words pointed to a single attacker. But Virginia’s strict 21-day deadline for reopening a case based on newly discovered evidence had long since passed. Legally, the DNA results were irrelevant.

So the defense team took a gamble. They dropped their appeals and asked then-Gov. L. Douglas Wilder (D) for a pardon. Wilder learned that the DNA results could not completely rule Washington out.

“I suspected the evidence showed some kind of coercion in the confession, but I didn’t have the proof,” Wilder said.

In 1994, Wilder commuted Washington’s sentence to life in prison and urged the legislature to change the 21-day deadline for submitting new evidence so that the inmate could go back to court.

Six years passed. Washington’s parents died, and the inmate grew increasingly depressed. “I was mad with myself for getting my hopes up,” Washington said.

Then, last winter, his attorneys learned that DNA technology had improved to the point that their client could be ruled out entirely. They turned to Gilmore, who ordered the new tests.

This time, the results showed no trace of Washington at the crime scene. The semen on the blanket had DNA that matched the genetic fingerprint of a man already imprisoned for rape. The last remaining vaginal swab had faint traces of DNA from an unknown man who was neither Washington, Clifford Williams nor the felon – widening the mystery. State police are questioning the imprisoned felon, but he has not been charged.

The governor pardoned Washington for the murder. But he left the inmate in prison to serve the remainder of his 30-year sentence for the Weeks attack. The parole board is considering Washington’s release, and he will be eligible for mandatory parole Feb. 12.

Gilmore’s legal counsel, Walter Felton, says the case points to the need for reform. “The governor’s office is not the place to retry cases,” he said. “The courts are the right forum with the right rules to look at new evidence.”

Timeline of a Tainted Death Penalty Case

June 4, 1982: Rebecca Lynn Williams, 19, a Culpeper mother of three, is stabbed 38 times in her apartment. Before passing out, she tells her husband and a neighbor that she was raped and stabbed by a black man.

May 21, 1983: Earl Washington Jr. is arrested by Fauquier County deputies after he breaks into the home of a neighbor and hits her with a chair. During two days of questioning, he confesses not only to attacking the neighbor, but also to a series of unrelated crimes, including the Williams killing.

Nov. 2, 1983: A judge rules that prosecutors can use Washington’s confession because the defendant understood his rights.

Jan. 18 – 20, 1984: Washington is tried and convicted of capital murder, and the jury recommends the death penalty.

May 13, 1985: Following the lead of the Virginia Supreme Court, the U.S. Supreme Court upholds Washington’s conviction. Virginia officials then set a Sept. 5 execution date, though Washington has no lawyer.

Aug. 27, 1985: The New York law firm of Paul, Weiss files for a stay of execution, which is granted five days before the planned electrocution.

Dec. 19, 1991: The 4th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals sends the case back for new hearings after learning that Washington’s blood type does not match the blood type of semen found on a blanket at the crime scene.

Sept. 17, 1993: After a lower court decides that the blood type evidence is inconclusive, the 4th Circuit upholds the death sentence, 2 to 1.

Oct. 25, 1993: A DNA test done by the Virginia state laboratory finds genetic material on Williams’s body that could not have come from Washington. But Virginia’s 21-day rule prevents Washington from going back to court.

Jan. 14, 1994: Gov. L. Douglas Wilder commutes Washington’s sentence to life in prison but does not pardon him.

June 1, 2000: Gov. James S. Gilmore III orders a new round of DNA testing. The results find no trace of Washington at the murder scene.

Oct. 2, 2000: Gilmore pardons Washington for the capital murder and reopens the investigation into Williams’s death.

December 2000: Washington, who is still serving a 30-year term for the attack on his neighbor, is being considered for early release, and a decision is expected shortly.