New York Daily News

By THOMAS M. DeFRANK

Daily News Washington Bureau Chief

It’s called the special housing unit at a place known as The Castle. But for the six soldiers on the military’s Death Row at Fort Leavenworth, Kan., life is no fairy tale.

Despite intense public and media interest in Timothy McVeigh’s execution, little attention has been paid to the six condemned soldiers incarcerated within the pale yellow-and-white walls of the U.S. Disciplinary Barracks.

One of those convicted murderers is in the last stages of a 12-year appeals process that may end with the first execution by the armed forces in more than 40 years.

Before Army Pvt. Dwight Loving of Rochester can be put to death, however, President Bush and the Supreme Court must affirm his sentence — a process that could take another three years.

The case has languished at Army headquarters since December 1998, when the Supreme Court declined to hear Loving’s appeal of his conviction for murdering two cab drivers near Fort Hood, Tex.

Experts Predict More Delays

A senior Army legal official confirmed that the case now awaits a decision by Army Secretary Thomas White. Because of various procedural issues, that decision isn’t imminent, he added, and outside legal experts predicted it will be several months before the case goes to Bush.

Under the Uniform Code of Military Justice, the commander-in-chief must personally approve all death sentences. There’s little doubt that will happen — as governor of Texas, he signed 151 death warrants, commuting only a single sentence.

The six current inmates on Fort Leavenworth’s Death Row are enlisted men in their mid-30s — three soldiers and three Marines. Four are black, one Asian-American and one white.

Ronald Gray has been there more than 13 years. The newest member is Jesse Quintanilla, a Marine from Guam who arrived in January 1998.

Critics charge that military death verdicts are seriously flawed, especially because soldiers can be sentenced to death by a jury of as few as five other soldiers — not the 12 jurors required by the federal government and all 38 states with a death penalty.

“On a day-to-day basis, the military justice system is very fair, but it has its peculiarities,” says Dwight Sullivan of the American Civil Liberties Union of Maryland and a former Marine Corps lawyer. “And those peculiarities really come to the forefront in death-penalty cases.”

Since the last military execution, the method of death has changed twice. Army Private John Bennett, convicted of the 1955 rape and attempted murder of an 11-year-old Austrian girl, was hanged at Fort Leavenworth in 1961.

The electric chair that replaced the gallows was never used and was recently donated to the Army’s military police museum in Missouri. Lethal injection is now the prescribed method. Leavenworth’s basement “special processing unit” is virtually identical to the death chamber where McVeigh met his fate in Terre Haute, Ind.

Even if Bush signs his death warrant, Loving can appeal to federal courts and, ultimately, to the Supreme Court again. That could easily take three years. President Dwight Eisenhower signed Bennett’s death warrant in 1958, for example, but he wasn’t executed until John F. Kennedy was President.

The last presidential death-penalty action was in 1963, when Kennedy commuted to life imprisonment the sentence of a Navy enlisted man convicted of murdering an officer. In 1997, President Bill Clinton added life without parole as an alternative to the death penalty — a sentence currently being served by four soldiers.

Sentences Commuted to Life

Though military executions have become increasingly rare, an estimated 465 soldiers have been executed since the Civil War, most for desertion in wartime and mutiny.

In 1983, a military appeals court ruled the military death penalty unconstitutional because sentencing guidelines didn’t require a finding of “aggravating circumstances.”

As a result, the seven inmates then on Leavenworth’s Death Row had their sentences commuted to life imprisonment. One has been denied parole every year since and is still at The Castle. The other six were scattered to federal prisons.

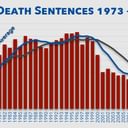

A year later, President Ronald Reagan reinstated the death penalty with an executive order setting out clear sentencing guidelines. By 1988, Leavenworth’s Death Row began receiving new occupants.

Critics charge that the military’s capital-punishment system is even more flawed than its civilian counterpart. African-American soldiers are sentenced to death in far greater numbers than whites. Moreover, the same senior officer who has already decided that a crime will be tried as a capital case also picks the jurors. And critics say inexperienced military death-penalty defense attorneys often provide inadequate counsel.

The system’s defenders reply that military personnel have more appellate options than other death-sentence felons — including both military and civilian courts and two separate appeals to the U.S. Supreme Court.