By JAMES LIEBMAN1, JEFF FAGAN and VALERIE WEST

Special to The National Law Journal

EARLIER THIS summer, we published a study of the death penalty in this country. Our findings were disturbing and have provoked strong reactions. Two months later, it is time to look at some of those reactions, clarify misunderstandings and underline our central claim that the death penalty system is deeply flawed.

Looking at thousands of death verdicts reviewed by courts in 34 states over 23 years, we found that nearly seven in 10 were thrown out for serious error, requiring 2,370 retrials. For cases whose outcomes are known, an astonishing 82% of retried death row inmates turned out not to deserve the death penalty; 7% were not guilty. The process took nine years on average. Put simply, most death verdicts are too flawed to carry out, and most flawed ones are scrapped for good. One in 20 death row inmates is later found not guilty.

Some criticisms of our study misstate our methods and findings. For example, we did not count wholesale reversals in 1976, when the Supreme Court voided many states’ capital statutes, but only those in states with valid statutes. We did not count reversals of verdicts that a higher court reinstated.

Liberal federal judges are not responsible for reversals: 90% were by elected state judges. Most federal reversals occurred when a majority of judges were Reagan and Bush appointees.

We did not manipulate statistics because we oppose the death penalty. We counted outcomes of all death sentences, asking a simple question: Was the verdict approved, or thrown out by the courts?

One critique focused on a single typographical error misreporting one Florida retrial outcome. But digging deeper for Florida data showed that we undercounted Florida reversals. This indicates that the error rates we report are likely conservative: If no errors are found, prisoners are executed. Their cases are easy to track. It’s harder to find reversals that release people from death row.

Significant errors

Errors leading to reversal are not “technicalities.” Virtually none were police seizures of reliable evidence. Where known, 80% were egregiously incompetent lawyering, police suppression of evidence of innocence, faulty jury instructions and biased judges and jurors ¯ errors that courts and studies have found are likely to put the wrong people on death row.

Some readers ask valid questions. Capital cases can go through three stages of court review. Our data on how often retrial outcomes change cover verdicts thrown out at the second stage. What can be said about the other stages? The first level of court review catches the most glaring errors, so these reversals may lead to more, not fewer, changed outcomes. The third stage is similar to the second, so their retrial outcomes may be similar.

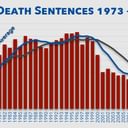

It took time to document all such reversals that occurred between 1973 and 1995. Have things changed in the meantime? There is evidence that our system of finding and curing errors has weakened, but there is no reason to think that cases reviewed in 1999 were less error prone than those in 1995.

Finally, our critics say that focusing on high rates of seriously flawed capital verdicts (1) avoids the crucial issue of the morality of capital punishment, (2) shows that the system works or (3) is irrelevant absent proof that innocent people are being executed.

Our study aims to put aside moral dilemmas that can’t be solved and ask a question managers, consumers and citizens answer every day: What do error rates say about whether a system does what it’s supposed to do and avoids serious risk? If 68% of an airline’s planes fail inspection and 82% sent for repairs are permanently grounded, the meaning is clear. The system is broken. No one would say, “The airline works. It’s good at catching mistakes.” And no one would fly the few planes that pass inspection ¯ even though no one has yet turned up dead. The risk is too high.

Our current death penalty system does not “work” when two of three death verdicts are too flawed to serve their purpose, when most can’t be salvaged and when the cost of each failed verdict is measured in hundreds of thousands of tax dollars, decades of time and untold anguish for victims needing closure.

Nor can death verdicts getting through the system be trusted. High error rates mean that all verdicts are suspect. They also overwhelm the review system. Forty percent of verdicts passing the first two judicial checkpoints prove flawed at the last one. What would a fourth check find?

Chronically high capital error rates are the warning light in the cockpit. We ignore them at our peril.

Mr. Liebman is a professor and Mr. Fagan a visiting professor at Columbia University School of Law. Ms. West is a Ph.D. candidate in sociology at New York University.