New Jersey Senator Raymond Lesniak delivered the following speech at the Memorial de Caen International Human Rights Competition in Caen, France on Sunday, February 1,2009. The competition included lawyers from Washington, D.C., France, Belgium, Guinea, Senegal, and Switzerland with speech topics ranging from governmental to military abuses of human rights.

The Senator’s speech below won first place in the international competition. He will donate his first-place winnings, roughly $9,740 from the Caen City Council, to The Road to Justice and Peace: a non-profit started by the Senator to advance the abolition of the death penalty around the globe, to support the families of murder victims, and to promote humane alternatives to

incarceration.

I come here today not to plead a case for a victim whose fundamental human rights have been violated. But, rather, to plead the case that the death penalty violates the fundamental human rights of mankind. In my country, The United States of America, over 3,000 human beings are awaiting execution, some for a crime they did not commit. I plead the case that the death penalty in the United States, Iraq, Pakistan, Japan, wherever, exposes the innocent to execution, causes more suffering to the family members of murder victims, serves no penal purpose and commits society to the belief that revenge is preferable to redemption.

On December 17, 2007, New Jersey became the first state in the Union to abolish the death penalty since the U.S. Supreme Court reinstated it in 1976. When Governor Jon Corzine signed the legislation I sponsored into law, he also commuted the death sentences of eight human beings. The Community of Sant’Egidio in Rome, Italy, a lay Catholic organization committed to abolishing the death penalty throughout the world, lit up the Roman Coliseum to celebrate this victory for human rights.

How was this victory achieved? First, by demonstrating that the death penalty creates the possibility of executing an innocent human being. One of our founding founders, Benjamin Franklin, quoting the British Jurist William Blackstone, said: “It’s better to let 100 guilty men go free than to imprison an innocent person.” Yet Governor Corzine and my legislation let no guilty person go free. It merely replaced the death penalty with life without parole, eliminating the possibility of putting to death an innocent human being.

Byron Halsey could have been one such human being. On July 9, 2007, Byron walked out of jail a free man after serving 19 years in prison for a most heinous crime: the murder of a seven year old girl and an eight year old boy. Both had been sexually assaulted, the girl was strangled to death, and nails were driven into the boy’s head.

Halsey, who had a sixth grade education and severe learning disabilities, was interrogated for 30 hours shortly after the children’s bodies were discovered. He confessed to the murders and, even though his statement was factually inaccurate as to the location of the bodies and the manner of death, his confession was admitted into evidence in a court of law. The prosecution sought the death penalty.

Halsey was convicted of two counts of felony murder and one count of aggravated sexual assault. He was sentenced to two life terms: narrowly evading the death penalty by the vote of one juror who held out against it during the sentencing portion of his trial.

After spending nearly half his life behind bars, post-trial DNA analysis determined, with scientific certainty, that Byron did not commit the murders. A witness for the prosecution at his trial is now accused of those crimes.

But for the good judgment of that one juror, Mr. Halsey might have been executed, and the real killer would never have been discovered and brought to justice.

Stories like Byron’s are not uncommon. Since 1973, 130 human beings on death rows throughout the United States have been released from jail for being wrongfully convicted. During that time over 1,100 prisoners were executed. How many of them were innocent? 3,309 remain on death row throughout the U.S. How many of them are innocent? How many of the innocent will be executed?

It could be Troy Davis. He’s been imprisoned since 1989 in the State of Georgia for a murder he maintains he did not commit. In one of Davis’ numerous appeals, the Chief Justice of the Georgia Supreme Court said, “In this case, nearly every witness who identified Davis as the shooter at trial has now disclaimed his or her ability to do so reliably. Three persons have stated that Sylvester Coles confessed to being the shooter.” Coles had testified against Davis at the trial.

On September 23, 2008, less than two hours before Davis was due to be put to death by lethal injection, he received a stay of execution by the US Supreme Court. On October 14 the stay was lifted and the State of Georgia issued an Execution Warrant for October 27. Three days before this execution date, the 11th Circuit Court stayed the execution to consider a new appeal.

Will Troy Davis be the next innocent person saved from execution, or will he be the next innocent person executed? Does the death penalty serve any purpose, other than to do harm to everyone involved, and society in general? Does the death penalty even console the families of murder victims?

Not according to 63 family members of murder victims who stated, in a letter to the New Jersey Legislature:

“We are family members and loved ones of murder victims. We desperately miss the parents, children, siblings, and spouses we have lost. We live with the pain and heartbreak of their absence every day and would do anything to have them back. We have been touched by the criminal justice system in ways we never imagined and would never wish on anyone. Our experience compels us to

speak out for change. Though we share different perspectives on the death penalty, every one of us agrees that New Jersey’s capital punishment system doesn’t work, and that our state is better off without it.“

Or more specifically stated by Vicki Schieber whose daughter, Shannon, was raped and murdered, “The death penalty is a harmful policy that exacerbates the pain for murdered victims’ families.“

Some argue that the death penalty is a deterrent to murder, yet more than a dozen studies published in the past 10 years have been inconclusive on its deterrent effect.

In testimony before the Subcommittee on the Constitution, Civil Rights and Property Rights of the United States Senate Judiciary Committee in February 2006, Richard Dieter, Executive Director of the Death Penalty Information Center, testified that states without a death penalty statute have significantly lower murder rates than their counterparts with the death penalty. Mr. Dieter also testified that of the four geographic regions in the U.S., the South, which carries out 80% percent of all executions in the country, has the highest murder rate. Conversely, the Northeast, which

implements less than 1% of all executions, has the lowest murder rate in the nation.

Even those who believe the death penalty can act as a deterrent admit that existing research has inconclusive results. Professor Erik Lillquist of Seton Hall University School of Law testified that recent econometric studies conclude that the death penalty can act as a deterrent, but only if the death penalty is implemented in a “sufficient” number of cases. Conversely, he also maintained that other studies suggest that executions can cause a “brutalization effect,” in which the murder rate actually increases.

Professor Lillquist stated:

“It just may be impossible to know what the deterrent or brutalization effect is here … at least as an empirical matter — simply because we’re never going to have a large enough database that can be removed from the confounding variables, such that we can come to a conclusion. When scientists run studies in general, we try to do it in a controlled environment. You can’t do that with murders and the death penalty.“

Jeffrey Fagan, Professor of Law and Public Health, Columbia University and Steven Durlauf, Kenneth J. Arrow Professor of Economics, University of Wisconsin-Madison wrote in a letter to the Editor in the Philadelphia Enquirer on November 17, 2007:

“Serious researchers studying the death penalty continue to find that the relationship between executions and homicides is fragile and complex, inconsistent across the states, and highly sensitive to different research strategies. The only scientifically and ethically acceptable conclusion from the complete body of existing social science literature on deterrence and the death penalty is that it’s impossible to tell whether deterrent effects are strong or weak, or whether they exist at all.“

The professors concluded:

“Until research survives the rigors of replication and thorough testing of alternative hypotheses and sound impartial peer review, it provides no basis for decisions to take lives.“

While the death penalty inevitably executes the innocent, exacerbates the pain and suffering of families of murder victims and serves no penal purpose, the worse damage it does is to a society that believes it needs to seek revenge over redemption.

The need for revenge leads to hate and violence. Redemption opens the door to healing and peace. Revenge slams it shut.

A society that turns its back on redemption commits itself to holding on to anger and a need for vengeance in a quest for fulfillment that can not be met by those destructive emotions. Redemption instead opens the door to the space that asks healing questions in the wake of violence: questions of crime prevention, questions of why some human beings put such a low value on life that they readily take it from others, questions that help us understand how to help those impacted by violence; questions that take a back seat, and are often ignored, when our minds and emotions are filled with a need for revenge.

Thirty-six states and the federal government of the United States still impose the death penalty. The United States has more human beings in prison and more violence than just about every other civilized country in the world. As long as we continue to choose revenge over redemption, it’s likely we will continue to be a leader in the amount of violence and size of our prison population.

It doesn’t have to stay that way.

When New Jersey abolished its death penalty, it chose redemption over revenge, healing over hate, peace over war. We need more states and our federal government to make those same choices. Consider the following headlines which appeared side by side in the New York Times: “Iraqi Leaders Say the Way Is Clear for the Execution of ‘Chemical Ali’.” The other headline read: “Bomber at Funeral Kills Dozens in Pakistan.“

Both Iraq and Pakistan have the death penalty. After the announcement setting the execution date for “Chemical Ali,” San Jawarno, whose father and other family members were killed in attacks directed by “Chemical Ali” said, “Now my father is resting in peace in his grave because Chemical Ali will be executed.“

The two events, the bombing in Pakistan and the words of the bereaved son whose father was killed, are not unrelated. We must speak up, at every forum, in our homes, our churches, synagogues, mosques and temples, in our legislative bodies, wherever an opportunity exists, to convince political leaders, community leaders, religious leaders, anyone who will listen, that the death penalty has no reason to exist, promotes violence, and brings peace to no one: in the grave or not.

That was to be the end of my plea to abolish the death penalty. Then I read a report from Amnesty International about the 13-year-old girl who was stoned to death in a stadium packed with 1000 spectators in Kismayo, Somalia. Her offense? Islamic militants accused her of adultery after she reported she had been raped by three men.

Will this senseless, inhumane killing ever end?

Perhaps. The brutality of the death penalty and of Islamic militants can end, if we speak out against it, wherever it exists, in any shape, in any form.

The death penalty is a random act of brutality. Its application throughout the United States is random, depending on where the murder occurred, the race and economic status of who committed the murder, the race and economic status of the person murdered and, of course, the quality of the legal defense.

I’m proud of the people of the State of New Jersey for electing political leaders who ended this random act of brutality. And I applaud Amnesty International for alerting the good people of the world to the brutality of the Islamic militants in Somalia who stoned to death that poor girl.

No good comes from the death penalty, whether it’s imposed by duly elected governments, or by radical, religious fanatics. No good.

The burden of proof in the Court of Public Opinion should be on those advocating for the death penalty. That burden has not been met.

Just ask Byron Halsey. Or Troy Davis. Or, if you could, that 13 year old girl.

- — - — -

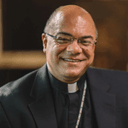

State Senator Raymond Lesniak chairs the (NJ) Senate Economic Growth committee and serves on the Judiciary and Commerce committees.