Washington Post

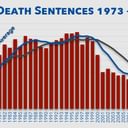

THE YEAR 2001 saw the continuation of what now appears to be a dramatic decline in the use of the death penalty in America. In 1999, 98 people were put to death. That number fell to 85 in 2000. But in the year just past, according to data from the Death Penalty Information Center, 66 people were executed. Texas, which has the dubious distinction of leading the nation in state-sponsored killing, cut executions by more than half (from 40 in 2000 to 17 in 2001) and lost the lead to Oklahoma, which executed 18 convicts in 2001. The top five death penalty states in 2001 — Oklahoma, Texas, Missouri (7), North Carolina (5) and Georgia (4) — accounted for 77 percent of executions. But no other state — including Virginia, with its historically hyperactive death chamber — executed more than two people.

The decline is an encouraging development for death penalty opponents. But caution is warranted. The decrease is only partly the result of a changing political climate. True, a combination of declining crime rates and a continuing wave of DNA exonerations has made the public and the courts more skeptical of death sentences. And demographic quirks in the death row population have played a significant, perhaps even predominant, role. But the climate could easily shift back. Now that it’s faltering, the booming economy, which presumably facilitated the decrease in crime over the past several years, could end up pushing crime rates in precisely the opposite direction. Views on capital punishment and the need to deal with terrorists with the firmest of hands also may have been hardened by the Sept. 11 attacks. Without systematic reform at both the state and federal levels — something that has begun but is far from complete — the current favorable trend in death penalty use could easily take a turn for the worse.

Unfortunately, one disturbing counter-trend has already been seen. In 2001, the federal government began executing people again, for the first time in decades. Shifting the federal death penalty into gear at exactly the time federal authorities ought to be pushing states to reform their own systems sends the wrong message. This problem will only grow worse if federal terrorism trials become common. Pressure in those cases for the death penalty may be even stronger than in routine criminal cases. It is, therefore, all the more critical to remember why capital punishment must be abolished. The death penalty doesn’t deter crime — much less terrorism. It is a capricious act toward human life on the state’s part. And it can produce disastrous, irreversible errors.