Opinions of the Court

REED V. GOERTZ, No. 21 – 442

Cert. granted: April 25, 2022

Argument: Oct. 11, 2022

Decided: April 19, 2023

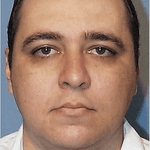

In a capital case from Texas, the Supreme Court ruled (6 – 3) in favor of Rodney Reed’s challenge to a Fifth Circuit decision that blocked access to DNA testing based on Texas’ statute of limitations.

Mr. Reed sought DNA testing of crime-scene evidence that he argued could support his innocence claim. The trial court denied the motion for DNA testing in 2014, and Mr. Reed appealed the ruling to the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals (TCCA). The TCCA remanded the case to the trial court and eventually affirmed the trial court’s decision against Mr. Reed in April 2017. The TCCA then denied a rehearing in October 2017. In August 2019, Mr. Reed filed suit in federal court to challenge the denial of testing under the federal civil rights statute 42 U.S.C. § 1983.

The District Court dismissed Mr. Reed’s suit because it found that he had failed to state a constitutional claim. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit affirmed the dismissal of Mr. Reed’s suit, but for different reasons. The Fifth Circuit found that Mr. Reed’s § 1983 suit was untimely because Mr. Reed failed to meet the 2‑year limitation for filing, which they held started with the Texas trial court’s denial of his DNA testing motion in 2014.

At the U.S. Supreme Court, Mr. Reed argued that the Fifth Circuit misinterpreted the law in calculating the 2‑year limitations period. Mr. Reed maintained that his § 1983 suit was timely because he brought the case within two years of the TCCA’s final decision on his DNA claim – the decision to deny a rehearing.

The question presented in Mr. Reed’s petition for certiorari was:

[W]hether the statute of limitations for a § 1983 claim seeking DNA testing of crime-scene evidence begins to run at the end of state-court litigation denying DNA testing, including any appeals (as the Eleventh Circuit has held), or whether it begins to run at the moment the state trial court denies DNA testing, despite any subsequent appeal (as the Fifth Circuit, joining the Seventh Circuit, held below).

The Court resolved the Circuit split in favor of Mr. Reed’s interpretation: “that the statute of limitations begins to run at the end of the state-court litigation.” The majority determined that “the soundness of that straightforward conclusion is reinforced by the consequences that would follow from a contrary approach,” such as plaintiffs having simultaneous federal and state claims for the same action. The opinion, authored by Justice Kavanaugh, was joined by Justices Roberts, Sotomayor, Kagan, Barrett, and Jackson.

Justice Thomas dissented on the grounds that the federal court lacked subject matter jurisdiction over Mr. Reed’s claim. Justice Alito, joined by Justice Gorsuch, dissented and argued that the statute of limitations should begin to run earlier in the process.

CRUZ V. ARIZONA, No. 21 – 846

Cert. granted: March 28, 2022

Argument: Nov. 1, 2022

Decided: Feb. 22, 2023

The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in favor of John Montenegro Cruz’s challenge to the Arizona Supreme Court’s denial of post-conviction relief. In state court, Mr. Cruz was appealing his death sentence because the trial court failed to instruct the jury about his ineligibility for parole, should he not be sentenced to death.

In 1994, the U.S. Supreme Court held in Simmons v. South Carolina that when future dangerousness is at issue in a capital case, a defendant has a due process right to inform jurors that he will not be parole eligible if he is not sentenced to death, assuming that is the alternative. Despite Simmons, the Arizona Supreme Court consistently held that Arizona capital defendants were not entitled to such a jury instruction about defendants’ parole ineligibility. The court reasoned that all defendants could receive executive clemency, so there was still a possibility of release. In 2016 in Lynch v. Arizona, the U.S. Supreme Court held Arizona’s interpretation to be unconstitutional of Arizona’s and made it clear that just like the defendant in Simmons, Arizona defendants convicted of capital offenses were “ineligible for parole under state law.”

Mr. Cruz was sentenced to death in 2005. After sentencing, the foreperson of the jury said: “Many of us would rather have voted for life if there was one mitigating circumstance that warranted it. In our minds there wasn’t. We were not given an option to vote for life in prison without the possibility of parole.”

Mr. Cruz raised the issue on direct appeal, but the Arizona Supreme Court decided that Simmons did not apply. After the U.S. Supreme Court’s 2016 Lynch decision, Mr. Cruz sought state post-conviction relief. Mr. Cruz argued that he was entitled to relief because Lynch was applicable retroactively as a significant change in the law. The Arizona Supreme Court denied relief on the grounds that Simmons was settled law and so his post-conviction claim was repetitive, while not addressing Cruz’s federal retroactivity arguments.

Justice Sotomayor called the state’s logic a “catch-22,” noting that Arizona was requiring Mr. Cruz and similarly situated petitioners to prove that Lynch was both a “significant change in the law,” and at the same time was an application of “settled” federal law to satisfy retroactivity requirements. The majority was joined by Justices Roberts, Kagan, Kavanaugh, and Jackson.

Justice Barrett wrote a dissenting opinion, claiming that the majority ruling was an improper interference with state law. The dissent was joined by Justices Thomas, Alito, and Gorsuch.

Grants of Review with Summary Dispositions

Burns v. Arizona, No. 21 – 847

On March 6, 2023, the Supreme Court issued an order granting certiorari to six death row petitioners from Arizona (Johnathan Burns, Steve Boggs, Ruben Garza, Fabio Gomez, Steven Newell, and Stephen Reeves), vacated the judgements from the Superior Court of Arizona, Maricopa County, and remanded the case for further consideration in light of its ruling in Cruz v. Arizona.

The petitioners raised the same claim as in Cruz (discussed above), that when their prosecutors raised the issue of their future dangerousness during sentencing hearings, they had a due process right to inform jurors that they would not be parole eligible if they were sentenced to life, and that the state court had misapplied both Simmons v. South Carolina and Lynch v. Arizona in refusing to allow them to do so.

Escobar v. Texas, 21 – 1601

On January 9, 2023, the Court issued a two-sentence order granting certiorari to Areli Escobar, vacating the judgment of the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals, and sending the case back for reconsideration.

At Mr. Escobar’s trial, prosecutors presented DNA, shoeprint, and fingerprint analysis from the Austin Police Department crime lab that purported to identify Mr. Escobar as the assailant in the rape and murder of 17-year-old Bianca Maldonado, who was stabbed 47 times. They also presented testimony from Mr. Escobar’s ex-girlfriend that she purportedly received a cellphone call in which she heard a woman repeatedly screaming over the course of ten minutes while being raped — although initially the girlfriend had told investigators only that she had heard Mr. Escobar having “consensual sex” with a woman.

The Austin crime lab was shut down in 2016 after a state investigation found several persistent and systemic issues that rendered results unreliable. Mr. Escobar requested state post-conviction relief based on these issues, and a state trial court ruled in his favor. The trial court found that the lab’s failures were widespread and included a “failure to adhere to scientifically accepted practices,” “suspect and victim-driven bias,” likely contamination of samples combined with a cavalier attitude that hampered the discovery of contamination, and untrained analysists supervised by leaders without necessary technical knowledge.

Based on evidence presented in state post-conviction proceedings, prosecutors concluded that “the State had offered flawed and misleading forensic evidence at Petitioner’s trial and this evidence was material to the outcome of his case in violation of clearly established federal due process law.” Despite this concession, the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals dismissed Mr. Escobar’s claims and denied his request for a new trial. The U.S. Supreme Court’s reversal requires the TCCA to reconsider the case “in light of the confession of error by Texas.”

Denials of Review with Statements by Individual Justices

Johnson v. Vandergriff, No. 23 – 5244

On August 1, 2023, the U.S. Supreme Court denied Johnny Johnson’s petition for a stay of execution. The stay was requested on the basis that Mr. Johnson was legally “insane” and therefore it was unconstitutional to execute him, under the Eighth Amendment and Supreme Court precedent.

In his petition for an evidentiary hearing on his competency to be executed, Mr. Johnson’s attorneys had presented evidence that he had a history of severe mental illness and believed that “Satan is ‘using’ the state of Missouri” to execute him as part of a plan to bring about the apocalypse, but that “he is a vampire and able to ‘reanimate’ his organs” and “enter an animals mind … in order to go on living after his execution.” In response, the state submitted a one-and-a-half-page affidavit from a professional counselor who, under Missouri law, is not qualified to make a formal determination of competency to be executed. The counselor also did not evaluate Mr. Johnson for competency to be executed but reported that Mr. Johnson had never expressed delusions when they met — which was for minutes at a time, sporadically, over a three-year period. A different doctor, who is qualified to determine competency, stated that Mr. Johnson did not meet the legal standard for competency to be executed. The Missouri Supreme Court rejected Mr. Johnson’s argument, as did the federal district court, but a three-judge panel on the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals issued a certificate of appealability. That decision was overruled by the Eighth Circuit en banc, on the legal standard that “no reasonable jurist” could debate the Missouri Supreme Court’s decision.

Justice Sotomayor, joined by Justices Jackson and Kagan, dissented from the denial. Justice Sotomayor wrote that the Missouri Supreme Court had misapplied the legal standard for competency to be executed, and concluded,

The Court today paves the way to execute a man with documented mental illness before any court meaningfully investigates his competency to be executed. There is no moral victory in executing someone who believes Satan is killing him to bring about the end of the world. Reasonable jurists have already disagreed on Johnson’s entitlement to habeas relief. He deserves a hearing where a court can finally determine whether his execution violates the Eighth Amendment. Instead, this Court rushes to finality, bypassing fundamental procedural and substantive protections.

Mr. Johnson was executed on August 1, 2023.

Barber v. Ivey, No. 23 – 5145

On July 21, 2023, the U.S. Supreme Court denied James Barber’s petition for a stay of execution. Mr. Barber had argued that executing him by lethal injection would violate the 8th Amendment’s ban on cruel and unusual punishment, citing Alabama’s previous botched executions, where the execution team spent hours trying and failing to establish IV access to prisoners. Mr. Barber argued that a recent review of execution protocols ordered by Governor Ivey had not resulted in any meaningful changes so there was a serious risk of those same errors repeating during his execution.

In three consecutive executions, the Alabama execution team spent hours unsuccessfully attempting to set IV lines, and in two of the three cases the death warrant expired before they were able to complete the execution. In those two cases, the prisoners survived and reported experiencing severe pain during the attempts. At that point, Alabama paused executions and began what it called a “top-to-bottom” review of its execution protocols, conducted by the Alabama Department of Corrections (ADOC), which is also responsible for conducting executions. The ADOC did not release a public report but did send a letter to Gov. Ivey stating that “no deficiencies” were found in the execution protocols. The ADOC also noted new rules passed by the Supreme Court of Alabama would extend the time the state had to conduct executions. State and federal courts denied Mr. Barber’s request for discovery regarding the internal review.

Justices Sotomayor, Kagan, and Jackson dissented from the Court’s denial. Justice Sotomayor authored the dissent, beginning by noting the Court’s precedent that a method of execution violates the Eighth Amendment when it causes “a substantial risk of serious harm.” She criticized the ADOC’s policy as “designed only to ensure that ADOC has aneven greater period of time in which to search the bodies of its prisoners for IV access. They do not address the unnecessary pain those prisoners may experience,” and negatively compared the ADOC’s investigation to other states that reviewed their lethal injection policies, emphasizing that others had independent reviewers and published official reports. Mr. Barber was executed on July 21, 2023.

Clark v. Mississippi, No. 22 – 6057

On June 30, 2023, the Supreme Court denied a petition for certiorari filed by Tony Clark, a death-sentenced man in Mississippi. Mr. Clark argued that the prosecutors in his case violated Batson v. Kentucky, the case which prohibits racial discrimination in jury selection.

Mr. Clark raised this claim twice during his initial trial when jurors of color were struck by the prosecution, but the trial court ultimately found that he had failed to show purposeful discrimination. During jury selection, the State struck Black jurors at much higher rates than white jurors. Prosecutors also conducted research about Black jurors to support striking them (which involved finding felons with the same last names as the Black jurors, did not involve asking the jurors if they were related to the felons, and was used as a justification even after the prospective jurors testified that none of their close family members had been prosecuted for felonies). The State’s race-neutral explanation was that it struck Black jurors because they had “equivocated” about their support for the death penalty in initial questionnaires, even though several of the Black jurors who were struck had given far more pro-capital punishment responses than several of the white jurors who were seated.

Justice Sotomayor listed these facts in her dissent (joined by Justices Kagan and Jackson), and wrote that the Mississippi Supreme Court did not address any of them in the majority opinion upholding Mr. Clark’s conviction and sentence. She argued that the majority’s silence on any of these factors should be sufficient for the Court to reverse the decision, but the cumulative effect “cries out for intervention by this Court.” She specifically drew parallels to Flowers v. Mississippi, a 2019 case which “made sure that lower courts understood how to apply Batson properly,” and which referenced statistical evidence of racial disparities in jury strikes, evidence of the State’s disparate investigation into and questioning of minority jurors, and the State’s misrepresentations when defending its strikes, all as evidence of a Batson violation. Justice Sotomayor concluded, “Apparently Flowers was not clear enough for the Mississippi Supreme Court, however. In yet another death penalty case involving a Black defendant, that court failed to address not just one but three of the factors Flowers expressly identified. … Today, this Court tells the Mississippi Supreme Court that it has called our bluff, and that this Court is unwilling to do what is necessary to defend its own precedent. The result is that Flowers will be toothless in the very State where it appears to be still so needed.”

Hamm v. Smith, No. 22 – 580

On May 15, 2023, the Supreme Court declined to review the Eleventh Circuit’s holding that Kenneth Eugene Smith had pled a viable Eighth Amendment claim when challenging Alabama’s lethal injection protocol and alternative method of execution.

In 2018, Alabama enacted a statute authorizing nitrogen hypoxia as an alternative method of execution to lethal injection but it has not carried out any executions with this new method. When a capital defendant argues that a method of execution violates the Eighth Amendment and is unconstitutionally cruel and unusual, the Supreme Court requires a defendant to plead a “feasible and readily implementable” alternative method of execution. The Eleventh Circuit held that because Alabama has a statute authorizing nitrogen hypoxia as an alternative method of execution, Smith met his initial burden. The State sought certiorari, which was denied.

Justice Thomas, joined by Justice Alito, dissented from the Court’s denial of certiorari. Justice Thomas argued that the Eleventh Circuit erred by holding that a method of execution which was authorized by statute was a “known and available alternative” since it had never been used in practice, and that Smith should be required to prove “the State’s unjustified refusal to adopt [a] proffered alternative despite its documented advantages, including its readily availability.”

Burns v. Mays, No. 22 – 58-91

On April 24, 2023, the Supreme Court denied Kevin Burns’ petition for certiorari regarding his death sentence without commenting on the reason for the denial. Mr. Burns argued that he had received inadequate assistance of counsel at the penalty phase of his trial, in violation of the Sixth Amendment’s right to counsel, because his trial level attorneys failed to present certain mitigation evidence at sentencing. Justice Sotomayor, joined by Justices Kagan and Jackson, dissented from the denial of certiorari.

Mr. Burns was convicted of felony murder, which only required that the jury determine he had participated in a felony resulting in death. During sentencing, he claimed that his attorneys performed inadequately by failing to introduce available evidence that, although he was guilty of participating in the felony, he had not been the gunman during the robbery, which could have served as mitigating evidence leading the jury not to sentence him to death. The Sixth Circuit held that whether he was the gunman was “residual doubt” evidence, or evidence that would indicate that he was not guilty of the felony murder charge, and that he could not claim that his counsel was ineffective on that basis. Mr. Burns appealed to the Supreme Court, arguing that the Sixth Circuit Court should have characterized the evidence as mitigation.

The dissent argued that the Sixth Circuit had erred in characterizing Mr. Burns’ evidence as residual doubt because Mr. Burns had only been convicted of felony murder – “the jury did not have to find that he shot anyone in order to convict him.” Therefore, evidence of whether he was the gunman went to the penalty phase deliberation, not to his underlying guilt, and evidence that he had not shot anyone could have been mitigatory. The dissent also argued that even if the characterization of “residual doubt” was correct, the Sixth Circuit erred in holding that the Supreme Court had not recognized a right to introduce residual doubt evidence during the penalty phase. They stated that under the precedential case of Strickland v. Washington attorneys should be measured by “an objective standard of reasonableness,” and hence the failure to present this important evidence could be considered ineffective assistance of counsel.

Brown v. Louisiana, No. 22 – 77

On April 3, 2023, the Supreme Court denied David Brown’s petition for certiorari regarding his conviction and death sentence. Brown’s petition argued that the state violated Brady v. Maryland when it failed to provide him with the statement of a co-defendant that indicated he was not involved in the murder for which he was sentenced to death, and that the lower courts misapplied Brady by not classifying the statement from the co-defendant as “favorable” to Mr. Brown.

Mr. Brown was convicted along with four co-defendants of the murder of a prison guard during an escape attempt. Mr. Brown has consistently maintained that he was not present when the guard was killed. After he was sentenced to death, his counsel discovered that the prosecution had previously obtained a statement from one of his co-defendants describing the murder, and the co-defendant did not mention Mr. Brown being present. His counsel argued that if they had had access to that confession during his trial, Mr. Brown may have received a lesser conviction or sentence, as it would have supported the theory that he was not present during the murder. The Louisiana Supreme Court rejected this argument.

Justice Jackson, joined by Justices Sotomayor and Kagan, dissented from the denial of certiorari. The dissent stated that under Brady v. Maryland, Mr. Brown had a right to all material evidence that was “favorable” (meaning to have “some value”) to his case. Because having a “relatively minor” role in a crime is mitigating under Louisiana law, Justice Jackson explained she would have granted certiorari and reversed the lower court’s decision because “the Louisiana Supreme Court misinterpreted and misapplied our Brady jurisprudence in a manner that contravenes settled law.”

Chinn v. Shoop, No. 22 – 5058

On November 7, 2022, the Supreme Court denied certiorari review of Davel Chinn’s Ohio conviction and death sentence. Chinn argued that Montgomery County prosecutors violated Brady v. Maryland by failing to provide evidence to the defense that could have impeached the credibility of a key prosecution witness, and that the appellate courts applied the wrong standard to determine whether this omission was material.

Mr. Chinn was convicted of a murder during the course of a robbery, largely based on the testimony of a supposed accomplice, Marvin Washington, who is intellectually disabled, which “may have affected [his] ability to remember, perceive fact from fiction, and testify accurately.” Although Mr. Washington’s disability was documented in his juvenile records (which stated that he had an IQ of 48), the State did not provide those records to the defense prior to Mr. Chinn’s trial. During Mr. Chinn’s direct appeal, the Ohio Supreme Court stated that the prosecution’s case hinged on Mr. Washington’s testimony. However, during post-conviction appeals, when Mr. Chinn’s counsel raised the Brady claim, the state courts determined that the evidence about the witness’s credibility was not “material” enough to affect the trial.

Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson, joined by Justice Sonia Sotomayor, dissented from the Court’s denial of certiorari. The dissent focused on “the relatively low burden that is ‘materiality’ for the purposes of Brady and Strickland.” It stated that the standard set by those cases, that there is a violation of the defendant’s rights if there is a “reasonable probability of a different outcome” if the misconduct did not occur, is lower than the “more probable than not” preponderance of the evidence standard. The dissent noted that although the Sixth Circuit purported to recognize that the standards were different, it also claimed that the standards were “effectively the same,” and incorrectly applied a higher “preponderance of the evidence” evaluation to Mr. Chinn’s claim.

Thomas v. Lumpkin, No. 21 – 444

On October 11, 2022, the Supreme Court denied certiorari review of Andre Thomas’ conviction and death sentence. Thomas argued that he was tried by a racially biased jury and that his attorneys provided ineffective representation by failing to remove racially biased individuals during jury selection.

Mr. Thomas was convicted by an all-white jury of murdering his wife, their son, and his wife’s daughter from a previous relationship. Notably, Mr. Thomas is Black, his wife and her daughter were white, and their son was biracial. Three of the jurors who decided Mr. Thomas’ fate indicated on written pre-trial questionnaires that they opposed interracial marriage or did not believe interracial couples should have children. Mr. Thomas’ attorneys failed to question two of the jurors about their answers and did not attempt to prevent any of them from sitting on the jury.

Justice Sonia Sotomayor, joined by Justices Elena Kagan and Ketanji Brown Jackson, dissented from the denial of certiorari. She wrote that Mr. Thomas’ trial counsel “fell far below an objective standard of reasonableness” by failing to question or object to the potential jurors who opposed interracial marriage in a case centered on an interracial family. Further, the state court’s finding that Mr. Thomas was not prejudiced by his attorney’s actions “violated clearly established law,” because “seating even one biased juror infringes on a criminal defendant’s Sixth Amendment right” to an impartial jury. Justice Sotomayor wrote that courts must “safeguard the fairness of criminal trials by ensuring that jurors do not harbor, or at the very least could put aside, racially biased sentiments.”