Battle Scars: Military Veterans and the Death Penalty

Posted on Nov 10, 2015

- Executive Summary

- Infographics Related to the Report

- Media Coverage of the Report

- Additional Information

Executive Summary Top

In many respects, veterans in the United States are again receiving the respect and gratitude they deserve for having risked their lives and served their country. Wounded soldiers are welcomed home, and their courage in starting a new and difficult journey in civilian life is rightly applauded. But some veterans with debilitating scars from their time in combat have received a very different reception. They have been judged to be the “worst of the worst” criminals, deprived of mercy, sentenced to death, and executed by the government they served.

Veterans with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) who have committed heinous crimes present hard cases for our system of justice. The violence that occasionally erupts into murder can easily overcome the special respect that is afforded most veterans. However, looking away and ignoring this issue serves neither veterans nor victims.

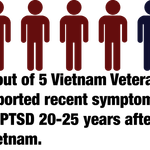

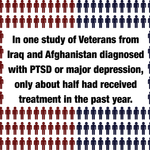

PTSD has affected an enormous number of veterans returning from combat zones. Over 800,000 Vietnam veterans suffered from PTSD. At least 175,000 veterans of Operation Desert Storm were affected by “Gulf War Illness,” which has been linked to brain cancer and other mental deficits. Over 300,000 veterans from the Afghanistan and Iraq conflicts have PTSD. In one study, only about half had received treatment in the prior year.

Even with these mental wounds and lifetime disabilities, the overwhelming majority of veterans do not commit violent crime. Many have been helped, and PTSD is now formally recognized in the medical community as a serious illness. But for those who have crossed an indefinable line and have been charged with capital murder, compassion and understanding seem to disappear. Although a definitive count has yet to be made, approximately 300 veterans are on death row today, and many others have already been executed.

Perhaps even more surprising, when many of these veterans faced death penalty trials, their service and related illnesses were barely touched on as their lives were being weighed by judges and juries. Defense attorneys failed to investigate this critical area of mitigation; prosecutors dismissed, or even belittled, their claims of mental trauma from the war; judges discounted such evidence on appeal; and governors passed on their opportunity to bestow the country’s mercy. In older cases, some of that dismissiveness might be attributed to ignorance about PTSD and related problems. But many of those death sentences still stand today when the country knows better.

Unfortunately, the plight of veterans facing execution is not of another era. The first person executed in 2015, Andrew Brannan, was a decorated Vietnam veteran with a diagnosis of PTSD and other forms of mental illness. Despite being given 100% mental disability by the Veterans Administration after returning from the war, Georgia sought and won a death sentence because he bizarrely killed a police officer after a traffic stop. The Pardons Board refused him clemency. Others, like Courtney Lockhart in Alabama, returned more recently with PTSD from service in Iraq. He was sentenced to death by a judge, even though the jury recommended life. The U.S. Supreme Court turned down a request to review his case this year.

This report is not a definitive study of all the veterans who have been sentenced to death in the modern era of capital punishment. Rather, it is a wake-up call to the justice system and the public at large: As the death penalty is being questioned in many areas, it should certainly be more closely scrutinized when used against veterans with PTSD and other mental disabilities stemming from their service. Recognizing the difficult challenges many veterans face after their service should warrant a close examination of the punishment of death for those wounded warriors who have committed capital crimes. Moreover, a better understanding of the disabilities some veterans face could lead to a broader conversation about the wide use of the death penalty for others suffering from severe mental illness.

Infographics Related to the Report Top

Media Coverage of the Report Top

The release of Battle Scars: Military Veterans and the Death Penalty was widely covered by the national, state, and internatlional media. Among the outlets reporting were:

- Reuters

- NBC News (#3 in top 7 Stories of the Day)

- Washington Post

- TIME

- Newsweek

- USA Today

- The New Yorker

- Los Angeles Times

- Boston Globe

- SFGate

- Texas Tribune

- Chicago Tribune

- Stars & Stripes

- Christian Science Monitor Washington Times

- Washington Examiner

- GQ Magazine

- Military.com

- Yahoo News

- Gawker

- CBS News Radio

- U.S. News & World Report

- The Nation

- New York Magazine

- Wall St Hedge

- Jet Magazine

- NYSE Post

- Oregon-Politics.com

- The Guardian

- Huffington Post

- AFP

- BuzzFeed

- Business Insider

- The Daily Beast (Number 6 on “Cheat Sheet”)

- Vice News Morning Bulletin

- CorrectionsOne

- Daily Mail

- Al Jazeera America

- China Post

- RT.com

- The Straits Times (AFP)

- Vox

Partial compilation of the texts and links of the articles.

Additional Information Top

Read the Battle Scars Press Release.

Last Day of Freedom is a richly animated personal narrative that tells the story of Bill Babbitt’s decision to stand by his brother, Manny, a Veteran returning from war, as he faces criminal charges, racism, and ultimately the death penalty. Manny’s case is also described in DPIC’s report, Battle Scars. The 2015 film is a portrait of a man at the nexus of the most pressing social issues of our day – veterans’ care, mental health access and criminal justice. Last Day of Freedom was nominated for an Oscar for Best Documentary – Short Subject and won the IDA (International Documentary Association) award for Best Short Documentary.

Directed by Dee Hibbert-Jones & Nomi Talisman (poster image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons).

The Rand Center for Military Health Policy Research, Invisible Wounds Mental Health and Cognitive Care Needs of America’s Returning Veterans