State & Federal

Arkansas

Timeline

1820 – First known execution in Arkansas, Thomas Dickinson hung for murder.

1913 – Arkansas replaces hanging with electrocution as its method of execution.

1967 – Arkansas Governor Winthrop Rockefeller declares a moratorium on executions

1970 – Governor Rockefeller grants clemency to all 15 men on death row

1972 – The Supreme Court strikes down the death penalty in Furman v. Georgia.

1973 – Arkansas passes a law reinstating capital punishment.

1976 – The Supreme Court reinstates the death penalty when it upholds Georgia’s statute in Gregg v. Georgia.

1990 – Arkansas resumes executions; abandons electrocution in favor of lethal injection as its method of execution.

1992 – Presidential candidate and Governor of Arkansas Bill Clinton leaves the campaign trail to oversee the execution of Ricky Ray Rector, who was intellectually disabled.

2001 — Arkansas Governor Mike Huckabee signs a law providing providing for Defense Counsel Standards and DNA testing.

2011 – Amid a nationwide execution drug shortage, Arkansas’ supply of one execution drug is seized by the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration.

2012 – The Arkansas Supreme Court finds part of the state’s capital punishment statute unconstitutional because it delegates too much authority to the Department of Corrections in carrying out executions.

2013 – The Arkansas legislature rewrites its execution protocol and passes a law shielding the identities of its execution drug suppliers; the Department of Corrections announces its intention to use phenobarbital for executions.

2015 – Arkansas Supreme Court upholds new execution protocol; Governor Asa Hutchinson sets dates for eight executions between October 2015 and January 2016, with four sets of double executions scheduled one month apart. The Arkansas Supreme Court imposes a stay on executions while evaluating the constitutionality of the 2013 secrecy law.

2016 – Arkansas Supreme Court upholds Arkansas secrecy law. The U.S. Supreme Court declines to review Arkansas death-row prisoners’ challenge to the state’s execution protocol.

2017 – Governor Asa Hutchinson sets dates for eight executions to be carried out in an unprecedented four sets of double executions over an 11-day period in April. Four are ultimately carried out and four are stayed. Executioners botched the executions of Jack Jones and Kenneth Williams.

2018 — Arkansas Supreme Court strikes down the state’s death penalty mental competency law for violating due process. The law previously gave the state’s prison director exclusive authority to determine a death row prisoner’s competency to be executed.

2020 — U.S. District Judge Kristine Baker rejects a claim, filed on behalf of seventeen inmates, that use of midazolam in lethal injection violates the constitutional ban on cruel and unusual punishment.

2022 — A federal appellate court upholds the constitutionality of the three-drug lethal injection protcol in Arkansas.

Famous Cases

Ricky Ray Rector

Rector was executed in 1992 for the murder of police officer Robert Martin. After shooting Officer Martin, Rector shot himself in the head in an apparent suicide attempt.

The suicide attempt destroyed his frontal lobe and left him severely brain damaged, rendering him incapable of understanding his pending execution. For his last meal, he left his pecan pie on the side of the tray, telling the guards who had come to take him to the execution chamber that he was saving it “for later.”

It took a team of five executioners over 50 minutes to find a suitable vein in which to inject the lethal cocktail. During that time, witnesses heard continued moaning from the inmate as he was jabbed over and over again with the execution needle.

Despite Rector’s inability to understand the criminal charges filed against him or his resulting death sentence, Arkansas Governor Bill Clinton made of point of returning to Arkansas and overseeing Rector’s execution during his Presidential campaign, in order to show the electorate that he was not soft on crime.

Barry Fairchild

In 1995 Barry Lee Fairchild was executed for the 1983 murder of Marjorie Mason. Ms. Mason had been raped and shot twice in the head. Acting on a tip from an unnamed informant now known to be inaccurate, the police surrounded Barry Fairchild and released their dog on him. He was bitten on the neck, side, and head. After being treated for the dog bites, he was questioned throughout the night and gave two conflicting confessions.

During his trial, Fairchild recanted his confessions and testified that Sheriff Tommy Robinson beat him and threatened to kill him if he did not confess. He testified that when he told the police he knew nothing of the crime, the sheriff hit him on the head with a shotgun and another man kicked him in the stomach. He said he had been rehearsed for twenty minutes on what to say on tape.

No physical evidence ever linked Fairchild to Mason’s rape or murder: no fingerprints on her belongings could be matched to his; a hat found near the crime scene and identified by witnesses as Fairchild’s contained no strands of his hair; semen found on the victim’s body was inconsistent with his blood type. Nonetheless, the jury found Fairchild guilty of rape and murder.

During subsequent appeals, thirteen men publicly disclosed that they too had been detained for questioning about the Mason murder and were tortured. They testified that they had been subjected to violent beatings, and that guns had been put to their heads while they were told to confess. One of these men reported that he heard deputies in the next room torture Fairchild into confessing.

During the fourth petition the judge found that the evidence showed that Fairchild was “not the one who shot and killed Ms. Mason,” but was an accomplice. As such, the death sentence was reversed, and a sentence of life in prison without parole was imposed in its stead.

In 1994, the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals reversed the lower court’s decision, and without refuting the legal conclusion that the Arkansas capital punishment statute had been violated, the Appellate Court held that it was too late to make this argument. The death sentence was reinstated, and Fairchild became the eleventh Arkansan put to death under the state’s modern capital punishment statute.

Damien Echols

Damien Echols was one of the “West Memphis Three,” wrongly convicted in 1994 of the murders of three 8‑year old Cub Scouts the year before. Echols, who had been sentenced death, and his co-defendants Jason Baldwin and Jessie Misskelley, who received life sentences, entered no-contest pleas in 2011 exchange for their freedom, after newly available DNA evidence failed match any of them to the crime scene. The three were convicted after Misskelley, who is borderline intellectually disabled, falsely confessed to the crimes following nearly 12 hours of interrogation. Misskelley implicated Echols and Baldwin, although portions of his confession did not match details of the case.

Kenneth Williams

On April 27, 2017, Kenneth Williams was executed during the course of a week in which eight executions had been scheduled to be carried before the state’s supply of the controversial execution drug, midazolam, expired. Media witnesses reported observing Williams “coughing, convulsing, lurching, jerking, with sound that was audible even with the microphone turned off” during his execution. Associated Press reporter Kelly Kissel said “Williams’ body jerked 15 times in quick succession — lurching violently against the leather restraint across his chest.” Kissel, who has witnessed ten executions, noted that “[t]his is the most I’ve seen an inmate move three- or four-minutes in.”

Notable Exonerations

Rickey Dale Newman

An Arkansas trial judge dismissed all charges against former death-row prisoner, Rickey Dale Newman on October 11, 2017, exonerating the intellectually disabled man after nearly 16 years imprisonment for a February 2001 murder. The former Marine also was seriously mentally ill and homeless — suffering from major depression and chronic posttraumatic stress disorder from childhood abuse — at the time he was charged with murdering Marie Cholette. After coercive interrogations by police, Newman came to believe he had committed the murder and falsely confessed, although the physical evidence contradicted his confession. The court found him competent to stand trial permitted him to represent himself. Following a one-day trial in which Newman told the jury he had committed the murder and asked them to impose the death penalty, he was convicted and sentenced to death in June 2002. No physical evidence linked Newman to the murder and DNA evidence on the blanket on which the victim was found excluded Newman. Nonetheless, a prosecution expert falsely testified that hair found on Newman’s clothing had come from the victim.

Newman subsequently sought to waive his appeals and be executed. However, four days before his scheduled execution on July 26, 2005, he permitted federal public defenders to seek a stay of execution. His lawyers obtained DNA testing of the hair evidence that disproved the prosecution’s trial testimony. They also discovered that prosecutors had withheld from the defense evidence from the murder scene that contradicted Newman’s confession. A federal court hearing also provided evidence that the state’s mental health doctor had made significant errors in administering and scoring tests he had relied upon in testifying that Newman had been competent to stand trial.

Notable Clemencies

Governor Winthrop Rockefeller, who declared a moratorium on executions when he took office in 1967, granted clemency to all fifteen men on death row in December of 1970.

Milestones in Abolition Efforts

In 2009 a near-unanimous Arkansas General Assembly created the Arkansas Legislative Task Force on Criminal Justice. The Task Force’s stated objective was to study judicial districts to determine if there is discrimination in how the most serious felonies, including capital cases, are handled and who is subject to these prosecutions. The Task Force was successful in identifying key areas where the state lacked adequate information gathering procedures.

In 1993, nine years before the U.S. Supreme Court banned the execution of people with mental retardation, the Arkansas criminal code was amended to create a mitigating circumstance for mental retardation in capital murder cases. This was due in large part due to public reaction to the execution of Ricky Ray Rector in 1992.

Other Interesting Facts

Since the Supreme Court upheld state statutes that reinstated capital punishment in 1976, Arkansas is the only state to have conducted three executions on the same night. It has done so twice:

On August 3, 1994, under Governor Jim Guy Tucker, the state executed Hoyt Franklin Clines, Darryl Richley, and James William Holmes.

On January 8, 1997, under Governor Mike Huckabee, the state executed Paul Ruiz, Earl Van Denton, and Kirt Douglas Wainwright.

Resources

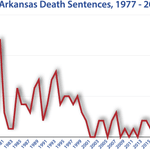

Arkansas Execution Totals Since 1976

News & Developments

News

Aug 12, 2025

Arkansas Death-Sentenced Prisoners File Lawsuit Challenging Constitutionality of State’s New Nitrogen Gas Execution Law

On August 5, 2025, a group of ten Arkansas death-sentenced prisoners filed a lawsuit challenging a new state law that authorizes their execution using nitrogen gas. Act 302, which Governor Sarah Huckabee Sanders signed into law in March 2025, went into effect on the same day the lawsuit was filed. The prisoners’ lawsuit argues that the new law is unconstitutional because it violates the state constitution’s separation of powers. All ten prisoners included in the…

Read MoreNews

Jun 04, 2025

2025 Roundup of Death Penalty Related Legislation

More than one hundred bills have been introduced this year in 34 states and in Congress to expand and limit use of the death penalty, abolish and reinstate the death penalty, modify execution protocols and secret the information about them, and alter aspects of capital trials. Thus far, nine bills in five states have been enacted, with Florida enacting the most legislation. Of the bills that have been signed into law, three modify execution protocols; two expand…

Read MoreNews

Apr 29, 2024

Arkansas Supreme Court Decision Allows New DNA Testing in Case of the “West Memphis Three,” Convicted of Killing Three Children in 1993

Damien…

Read MoreNews

Apr 27, 2022

Arkansas Marks Five Years Since End of 2017 Execution Spree

On April 27, 2017, Kenneth Williams convulsed violently as he died on the gurney, the fourth prisoner put to death in an eleven-day execution spree in which Arkansas intended to execute eight men before its supply of execution drugs expired. It has not…

Read MoreNews

Aug 18, 2021

Federal Appeals Court Upholds Ruling Barring Death Penalty for Intellectually Disabled Arkansas Death-Row Prisoner Alvin Jackson

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit has upheld a federal district court ruling that Arkansas death-row prisoner Alvin Jackson is ineligible for the death penalty because of intellectual…

Read More