Today, the DPIC office is closed in observance of Juneteenth, which celebrates the emancipation of enslaved people in the United States. As we commemorate this holiday, we remember the historical relationship between slavery, lynching, Jim Crow segregation, and the death penalty and their use as instruments of social control to maintain racial hierarchy. Our September 2020 report, Enduring Injustice, delves into the historical use of capital punishment, providing context for the racial disparities that persist in the modern death penalty system. The story below accompanied the release of that report. DPIC’s overview page on Race and the Death Penalty also provides valuable resources, including links to studies, data, and news on the issue.

The Death Penalty Information Center has released a major new report on race and the U.S. death penalty, providing an in-depth look at the historical role race has played in the death penalty and detailing the pervasive impact racial discrimination continues to have throughout every stage of a death penalty case today. Enduring Injustice: the Persistence of Racial Discrimination in the U.S. Death Penalty, released on September 15, 2020, also makes the case for why redressing discrimination in the American death penalty is essential if the United States is serious about creating a fair and just criminal legal system.

In early news coverage of the report, the Associated Press wrote: “The report from the Death Penalty Information Center is a history lesson in how lynchings and executions have been used in America and how discrimination bleeds into the entire criminal justice system. It traces a line from lynchings of old — killings outside the law — where Black people were killed in an effort to assert social control during slavery and Jim Crow, and how that eventually translated into state-ordered executions.”

“The death penalty is inextricably linked to our history of slavery, of lynching, and Jim Crow segregation, and we wanted to put what is happening today in its appropriate context,” DPIC Executive Director Robert Dunham told Associated Press. “[W]hat the data tells us and what history tells us is that they’re all part of the same phenomenon.”

The Memphis Commercial Appeal noted that the report was released in an environment of social upheaval in which “[o]pponents of the death penalty are finding their arguments about the history of state-sanctioned executions fit into a wider discourse about racial injustice amid nationwide protests against police brutality and racism.”

Ngozi Ndulue, DPIC’s Senior Director of Research and Special Projects and the author of the report, agreed. “We have seen more explicit reference to the continued racial discrimination in the death penalty in the last few months,” she told the Commercial Appeal. “This is a moment that advocates are really looking for concrete changes and what we’re trying to do with this report — the bulk of it was written before the deaths of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, George Floyd — ties really into the moment of reckoning of racial justice the country is having right now.”

The report documents the historic role the U.S. death penalty has played as an instrument of social control, tracing its use during slavery as a tool for controlling Black populations and curbing rebellions through the post-Civil War era in which lynchings and other extrajudicial violence rose in prominence and public officials promised legal executions as a means to discourage “vigilante justice.” As lynchings decreased in the early 20th century, the report says, executions began to take their place in some of the same circumstances that earlier would have ended in lynchings.

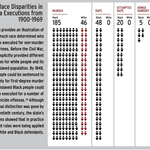

The report cites Virginia as an illustration of the racist deployment of capital punishment. “Before the Civil War, Virginia explicitly provided different penalties for white people and its enslaved population,” the report says. “By 1848, white people could be sentenced to death only for first-degree murder while enslaved Black people could be executed for a number of non-homicide offenses.” By the 20th century, the racial categorization of crimes was gone from the law books but was retained in practice. From 1900 through 1969, the report shows, 258 African Americans were executed, as compared to 46 whites. Forty-eight Black men were executed for rape, 20 for attempted rape, and 5 for armed robbery. No white person was executed for any crime that did not result in death. The same pattern prevailed across the South, with hundreds of African-American men condemned and executed for the alleged rape or attempted rape of white women or girls. No white man was ever executed for raping a Black woman or girl.

The report also explains that racial bias persists today, as evidenced by cases with white victims being more likely to be investigated and capitally charged; systemic exclusion of jurors of color from service in death-penalty trials; and disproportionate imposition of death sentences against defendants of color. “The death penalty has been used to enforce racial hierarchies throughout United States history, beginning with the colonial period and continuing to this day,” Ndulue said.

Among the evidence of continuing discrimination in the use of the death penalty, the report references:

- A 2015 meta-analysis of 30 studies showing that the killers of white people were more likely than the killers of Black people to face a capital prosecution.

- A study in North Carolina showing that qualified Black jurors were struck from juries at more than twice the rate of qualified white jurors. As of 2010, 20 percent of those on the state’s death row were sentenced to death by all-white juries.

- Data showing that since executions resumed in 1977, 295 African-American defendants have been executed for interracial murders of white victims, while only 21 white defendants have been executed for interracial murders of African Americans.

- A 2014 mock jury study of more than 500 Californians that found white jurors were more likely to sentence poor Latinx defendants to death than poor white defendants.

- Data showing that exonerations of African Americans for murder convictions are 22 percent more likely to be linked to police misconduct.

“Racial disparities are present at every stage of a capital case and get magnified as a case moves through the legal process,” Dunham said. “If you don’t understand the history, … you won’t understand why. With the continuing police and white vigilante killings of Black citizens, it is even more important now to focus attention on the outsized role the death penalty plays as an agent and validator of racial discrimination. What is broken or intentionally discriminatory in the criminal legal system is visibly worse in death-penalty cases. Exposing how the system discriminates in capital cases can shine an important light on law enforcement and judicial practices in vital need of abolition, restructuring, or reform.”

The death penalty’s “discriminatory presence as the apex punishment in the American legal system legitimizes all other harsh and discriminatory punishments,” Ndulue said. “That is why the death penalty must be part of any discussion of police reform, prosecutorial accountability, reversing mass incarceration, and the criminal legal system as a whole.”

Ngozi Ndulue, Enduring Injustice: the Persistence of Racial Discrimination in the U.S. Death Penalty, Death Penalty Information Center, September 15, 2020; Colleen Long, Report: Death penalty cases show history of racial disparity, Associated Press, September 15, 2020; Frank Green, Death penalty has been used to enforce racial hierarchies since colonial times, study concludes, Richmond Times-Dispatch, September 15, 2020; Katherine Burgess, Death penalty opponents see ties to nationwide reckoning over race as center releases new report, Memphis Commercial Appeal, September 15, 2020.

Read the DPIC media release.