DPIC 2022 Mid-Year Review: Geographic Isolation of Death Penalty Continues Amidst Eight-Year Trend of Minimal Use

Posted on Jul 01, 2022

- Introduction

- First-Half 2022 Death Sentences

- First-Half 2022 Executions

- Exonerations

- The Supreme Court

- Legislative Developments

Introduction Top

Long-term trends continued in the first half of 2022, with new death sentences and executions both on pace for continued historic lows. Use of the death penalty was confined to a small number of states that have historically been heavy users of capital punishment. The unavailability of execution drugs and the inability of states to competently carry out executions continued to shape executions and policies across the country, as prisoners continued to challenge lethal-injection protocols and states halted scheduled executions. At the same time, a small number of states undertook steps to ramp up future executions, three states passed new laws to create more secrecy and give more control over execution methods to state corrections officials, and the conservative supermajority on the U.S. Supreme Court continued to erode access to the courts and enforcement of constitutional rights.

First-Half 2022 Death Sentences Top

Even with the reopening of courts previously shuttered because of the pandemic, the pace of new death sentences in the first half of 2022 remained near record lows. DPIC has identified at least seven death sentences that were imposed in five states from January through June 2022, a pace below even the record sentencing lows set during the pandemic years of 2020 and 2021. Even with a significant surge of unanticipated death sentences in the second half of the year, the U.S. will almost certainly record its eighth consecutive year with fewer than 50 death sentences, more than 85% below the peak sentencing years of the mid 1990s.

Five of the seven defendants sentenced to death in the first half of 2022 are people of color: three are Black and two are Latinx. Two are white. All three Black defendants sentenced to death in the first half of the year were convicted of killing Black victims. Four of the year’s death sentences were imposed for the murders of police or correctional officers.

Ricky Dubose, who was sentenced to death in Putnam County, Georgia on June 16 for the murders of two correctional officers during an attempted escape, was found dead in his cell ten days later of an apparent suicide.

On May 23, a St. Charles County, Missouri trial judge rejected the state’s first jury recommendation for a death sentence in nine years and instead re-sentenced former death-row prisoner Marvin D. Rice to life without parole. The trial judge at Rice’s first trial in 2017 had sentenced him to death under Missouri’s controversial “hung jury” sentencing provisions after a single juror vote for death had prevented an otherwise unanimous jury from imposing a life sentence. Judge Daniel Pelikan considered the prior jury vote in imposing sentence, and found that the mitigating evidence in the case substantially outweighed the prosecution’s aggravating evidence.

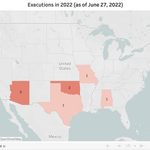

First-Half 2022 Executions Top

Nine states scheduled a total of 23 executions for the first half of 2022. Seven executions in five states were carried out, putting the nation on pace for its eighth consecutive year with fewer than 30 executions. Arizona and Oklahoma each executed two people. Alabama, Missouri, and Texas each executed one.

Ten active execution dates — five in Oklahoma, four in Texas, and one in Alabama — are pending at the start of the year’s second half. On June 6, Oklahoma federal district court Judge Stephen Friot denied a challenge 28 death-row prisoners had brought to the state’s lethal-injection protocol and, just four days later, Oklahoma Attorney John O’Connor filed a motion in the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals requesting the court to set 25 execution dates over a two-year period beginning in August 2022. On July 1, the court set 25 execution dates, five for 2022 and 20 for subsequent years.

Oklahoma executed Donald Grant on January 27. His was the third execution carried out by the state while the prisoners’ lethal-injection protocol lawsuit was pending in federal court. Grant’s attorneys argued that he should not be executed because he was seriously mentally ill and had brain damage. “Executing someone as mentally ill and brain damaged as Donald Grant is out of step with evolving standards of decency,” his lawyers told the Oklahoma Board of Pardons and Parole.

Just hours after Oklahoma executed Grant, Alabama executed Matthew Reeves, an intellectually disabled prisoner whose attorneys argued that the state had violated the Americans with Disabilities Act. Reeves had been given a form to choose between the state’s default execution method of lethal injection and its new, untested method of nitrogen hypoxia. The form required an 11th grade reading level, but the state offered no accommodations for prisoners like Reeves, who had an IQ in the upper 60s to low 70s. Because he did not fill out the form, the state sought an execution date for him. Alabama does not have a protocol in place for nitrogen hypoxia, so prisoners who opted in to the new method have not received execution dates. A federal district court issued an injunction blocking Reeves’ execution, but the U.S. Supreme Court, in a 5 – 4 opinion issued after Reeves’ execution had been scheduled to begin, lifted the injunction and allowed him to be executed.

Gilbert Postelle was executed on February 17. Postelle was 18 years old, intellectually impaired, mentally ill, and addicted to methamphetamines when, at the direction of his mentally ill father, he, his brother, and a fourth man participated in the fatal shootings of four people. He was the only one of the four perpetrators sentenced to death – his father was found incompetent to stand trial and the others received life sentences. His execution reflects a continuing trend in the U.S. in which states and the federal government have put to death vulnerable, less culpable defendants who are ineligible or barely eligible for the death penalty.

Postelle was the fourth and final person executed as part of a scheduled five-month, seven-person execution spree that Oklahoma announced after a six-year hiatus prompted by a string of botched executions. His execution took place just 11 days before a federal judge began hearing evidence on the constitutionality of the state’s lethal-injection protocol in a trial that was scheduled before the execution spree began.

With the executions of Grant and Postelle, Oklahoma County has carried out 44 executions. It is one of just five counties – along with Harris County (Houston), Dallas County, Bexar County (San Antonio), and Tarrant County (Fort Worth) in Texas – responsible for one-fifth of all U.S. executions since 1976.

Carl Wayne Buntion

Texas executed its oldest death-row prisoner, 78-year-old Carl Buntion, on April 21. Buntion had sought to halt his execution on grounds that his death sentence was predicated upon a false prediction that he would pose a continuing threat if spared the death penalty. His clemency petition, which was denied April 19, argued that “Mr. Buntion is a frail, elderly man who requires specialized care to perform basic functions. He is not a threat to anyone in prison and will not be a threat to anyone in prison if his sentence is reduced to a lesser penalty.” In his 31 years sentenced to death, “he has been cited for only three disciplinary infractions,” the petition said, “and he has not been cited for any infraction whatsoever for the last twenty-three years.”

Missouri prisoner Carman Deck was executed on May 3. Each of Deck’s three death sentences (all for the same crime) were overturned — once by the U.S. Supreme Court — as a result of prejudicial constitutional violations in his trials. Nonetheless, Missouri proceeded with his execution because a procedural technicality overturned his third grant of relief, blocking him from presenting his claim that critical mitigating evidence calling for a sentence less than death had become unavailable due to the long delays between his first, second, and third trials. In a stay application, his attorneys wrote, “[a] state should not be allowed to repeatedly attempt to obtain a death sentence, bungle the process, and then claim victory when no one is left to show up for the defendant at the mitigation phase.”

In May, Arizona resumed executions after a nearly eight-year hiatus following the botched two-hour execution of Joseph Wood on July 23, 2014. The state executed Clarence Dixon, who had been allowed to represent himself at his capital trial, despite having been found legally insane in an earlier trial for an unrelated assault. At a hearing on his mental competency to be executed, his lawyers presented evidence that he has schizophrenia with accompanying auditory and visual hallucinations and delusional thinking. The Navajo Nation, of which Dixon was a member, opposed his execution.

Dixon’s May 11 execution was characterized by experts as botched. Personnel attempted for 25 minutes to set an intravenous line in Dixon’s arms, then resorted to a bloody and apparently unauthorized “cutdown” procedure to insert the IV line in his groin.

The execution team again had difficulties setting an IV line a month later in the June 8 execution of Frank Atwood. Jimmy Jenkins, a reporter at the Arizona Republic, described the “surreal spectacle” of Atwood assisting executioners in finding a vein to inject the drugs that would kill him.

Atwood maintained his innocence, and sought a hearing to present new evidence supporting his claims. He also challenged the constitutionality of Arizona’s execution protocol, arguing that the lethal-injection procedure would cause him excruciating pain due to a spinal condition.

Courts or governors put scheduled executions on hold in a number of states. Ohio Gov. Mike DeWine issued a series of nine reprieves of executions set for 2022 in response to “ongoing problems involving the willingness of pharmaceutical suppliers to provide drugs” for use in executions “without endangering other Ohioans.” Drug manufacturers had informed the governor that they would halt selling medicines to state facilities if Ohio diverted drugs that had been sold for medical use and instead used them in executions.

Tennessee Governor Bill Lee

On April 21, Tennessee Governor Bill Lee issued a reprieve halting Oscar Franklin Smith’s execution less than a half-hour before it was scheduled to be carried out, after learning that corrections officials had failed to test execution drugs for bacterial endotoxins. Court documents later revealed widespread non-compliance by Tennessee execution personnel with many provisions in the state’s execution protocol. On May 2, Lee announced that Tennessee would not go forward with any of the executions scheduled in the state in the second half of 2022 and that the state had retained former U.S. Attorney Ed Stanton to conduct an independent review of Tennessee’s execution process. Executions are expected to remain on hold for the duration of that investigation and while court challenges to any revision of the state’s execution protocol are being litigated.

The South Carolina Supreme Court for the third time halted executions to resolve questions concerning the state’s compliance with its execution protocol. The Georgia state courts stayed the execution of Virgil Presnell after his lawyers argued that the state attorney general’s office had secured his death warrant in violation of an agreement not to schedule executions until six months after Georgia had resumed normal visitation at state prisons and a COVID vaccine had become “readily available to all members of the public.”

Exonerations Top

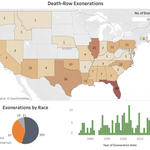

Samuel Randolph was exonerated from Pennsylvania’s death row. On April 6, 2022, two days after the U.S. Supreme Court had declined to review the county prosecutors’ appeal of a federal court ruling granting Randolph a new trial, District Attorney Fran Chardo filed a motion to enter an order of nolle prosequi terminating the prosecution of Mr. Randolph. Randolph’s conviction had been overturned by a federal district court nearly two years earlier because Randolph’s trial court had violated his Sixth Amendment right to be represented by counsel of choice by preventing counsel retained by Randolph’s family from entering his appearance in the case and forcing him to go to trial with an unprepared court-appointed lawyer with whom he had an “absolute[,] complete breakdown of communication.” Dauphin County prosecutors appealed the decision to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit, which affirmed the lower court’s ruling, and the U.S. Supreme Court, which denied review.

In DPIC’s research for the Death Penalty Census, two additional exonerations were uncovered, bringing the total number of death-row exonerations to 189.

Alexander McClay Williams (left) with then-District Attorney William J. McCarter

Pennsylvania posthumously exonerated Alexander McClay Williams, a Black teenager who was executed in 1931 on false charges that he had murdered a white woman. Williams was just 16 when he was killed in the electric chair, making him the youngest person ever executed in Pennsylvania. The court action was the culmination of years of effort by Williams’ family and Sam Lemon, the great-grandson of his trial lawyer, to clear the teen of the murder of his school matron, Vida Robare. Robare had actually been murdered by her abusive ex-husband shortly after she had obtained a divorce from him on grounds of “extreme cruelty.” Williams was represented at trial by William Ridley, the first African American admitted to the Bar of Delaware County. Ridley was provided just $10 to investigate and defend the case. An all-white jury convicted and condemned Williams based upon a confession coerced by police, after prosecutors withheld exculpatory evidence. The entire trial took less than a day. He was executed without an appeal. Delaware County District Attorney Jack Stollsteimer said, “We cannot rewrite history to erase the egregious wrongs of our forebearers. However, when, as here, justice can be served by publicly acknowledging such a wrong, we must seize that opportunity.”

In the first half of 2022, two people with strong innocence claims received significant nationwide attention.

Melissa Lucio

Texas set an execution date of April 27 for Melissa Lucio, a battered woman who was sentenced to death for what may have been an accidental fall that killed her two-year-old daughter. A bipartisan group of nearly 90 members of the Texas House of Representatives called on Governor Greg Abbott to grant clemency to Lucio. “The system literally failed Melissa Lucio at every single turn,” Rep. Jeff Leach (R – Plano), the chair of the House’s Criminal Justice Reform Caucus, said at a news conference. “As a conservative Republican myself, who has long been a supporter of the death penalty in the most heinous cases, I have never seen a more troubling case.” Just two days before the execution date, the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals stayed Lucio’s execution and directed the trial court to conduct a hearing on the evidence of her innocence.

Oklahoma death-row prisoner Richard Glossip also received support from state legislators, who released an independent review of his case. “We’ve got an individual sitting on death row that’s been there 25 years and I believe he’s totally innocent,” Oklahoma Rep. Kevin McDugle (R – Broken Arrow) said at a press conference on June 15. The 343-page report includes the revelation that the district attorney’s office told police to destroy a box of evidence before Glossip’s second trial. Records indicate the box included financial records, duct tape, and a shower curtain from the crime scene. Glossip has faced three execution dates, one of which was halted at the last minute because the state had obtained the wrong drug for his execution. He is the second of 25 prisoners for whom the Oklahoma Attorney General requested execution dates. “Given the thoroughness of the investigation and report, and the seriousness of the concerns it raises, it would be premature for this Court to set a date for Mr. Glossip’s execution,” Glossip’s attorneys said in their objection to setting an execution date. Despite these objections, Glossip’s execution has been scheduled for September 22, 2022.

The Supreme Court Top

Action and inaction by the conservative supermajority of the U.S. Supreme Court in the first half of 2022 continued to erode judicial enforcement of constitutional protections in death penalty cases. Since the retirement of Justice Anthony Kennedy and death of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, the Court has not ruled in favor of a death-row prisoner or stayed any execution on any issue related to the constitutionality of a capital conviction or death sentence.

In a partisan 6 – 3 decision authored by Justice Clarence Thomas on May 23, the Court, in the consolidated cases of Shinn v. Martinez Ramirez and Shinn v. Jones, judicially rewrote the federal habeas corpus statute to deny two Arizona death-row prisoners access to the federal courts to present evidence that their ineffective state court counsel had failed to develop. Calling federal court intervention to prevent an unconstitutional conviction or execution an “intrusion … [on] the State’s sovereign power to enforce ‘societal norms through criminal law,’” Thomas ruled that 1990s amendments to the federal habeas corpus law permit state prisoners who were provided ineffective representation at trial and in state post-conviction proceedings to argue that their counsel were ineffective but bar them from presenting evidence of that ineffectiveness that competent lawyers had discovered once the case had reached federal court. Barry Jones’ state court lawyers had failed to investigate available evidence that he was innocent and David Martinez Ramirez’s state court lawyers had failed to investigate evidence of intellectual disability that could have led a jury to spare his life.

Justice Sonia Sotomayor issued a scathing dissent, joined by Justices Stephen Breyer and Elena Kagan. She described the decision as “perverse” and “illogical,” writing that it “eviscerates” controlling case precedent and “mischaracterizes” other decisions of the Court. “The Court,” she wrote, “arrogates power from Congress[,] … improperly reconfigures the balance Congress struck in the [habeas amendments] between state interests and individual constitutional rights,” and “gives short shrift to the egregious breakdowns of the adversarial system that occurred in these cases, breakdowns of the type that federal habeas review exists to correct.”

On June 13, the Court refused to review a decision of the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals (TCCA) that for the second time had denied relief to Terence Andrus on his claim that his court-appointed lawyer had failed to investigate and present to his sentencing jury a “tidal wave” of available mitigating evidence. In June 2020, a 6 – 3 majority of the Court had reversed the TCCA’s prior decision denying relief, finding that counsel had unreasonably failed to investigate “abundant,” “compelling,” and “powerful mitigating evidence” that could have been presented to the jury to spare Andrus’ life. The Court remanded the case to the state court to reconsider whether this failure had been prejudicial. The TCCA responded with a 5 – 4 decision that “reiterate[d] … to the extent our holding was not clear … that we decided the issue of prejudice when the case was originally before us.”

Justice Sotomayor, joined by Justices Breyer and Kagan, dissented, writing that “Andrus’ case cries out for intervention, and it is particularly vital that this Court act when necessary to protect against defiance of its precedents.” Sotomayor also stated that by denying certiorari, the Court is permitting “defiance of vertical stare decisis,” which “substantially erodes confidence in the functioning of the legal system.”

The Court on June 30 also refused to review another Texas case involving glaring ineffectiveness of penalty-phase counsel for Anibal Canales to investigate and present mitigating evidence. In dissent, Justice Sotomayor noted that “The mitigating evidence put on by Canales’ counsel was so thin that the prosecutor remarked in closing that it was ‘an incredibly sad tribute that when a man’s life is on the line, about the only good thing we can say about him is he’s a good artist.’” Sotomayor wrote: “The legal errors … below, involving life-or-death stakes, are so clear that I would summarily reverse.”

On June 21, the first business day after the 20th anniversary of the Court’s landmark ruling in Atkins v. Virginia prohibiting the use of capital punishment against individuals with intellectual disability, the Court let stand a Florida case that created a procedural loophole that allows those executions to continue. In a one-line ruling, the Court summarily denied a petition for writ of certiorari filed on behalf of death-row prisoner Joe Nixon, declining to review the state’s refusal to apply to his case the Supreme Court’s 2014 ruling in Hall v. Florida that had struck down the unconstitutionally harsh criteria the Florida courts had previously used to deny his intellectual disability claim. The Court on February 28 had declined to disturb a case in which intellectually disabled death-row prisoner Rodney Young had challenged Georgia’s uniquely harsh requirement that the defendant must prove his or her intellectual disability beyond a reasonable doubt. Then, on June 30, the Court refused to hear the case of Ohio death-row prisoner Danny Hill, whose claim of intellectual disability had been denied despite what the three liberal justices described in dissent as “a mountain of record evidence” establishing his ineligibility for the death penalty.

Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson.

June 30 also marked the official retirement of Justice Stephen Breyer, a death-penalty skeptic who continued to his final days on the Court to urge the justices to reconsider the constitutionality of capital punishment. He was replaced on the Court by Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson, the first African-American woman and first former federal public defender to serve on the Court.

Legislative Developments Top

New laws expanded secrecy policies in two states, while another state passed a law barring the death penalty for people with serious mental illness.

State legislatures in Idaho and Florida passed secrecy bills to conceal from the public the identity of execution drug suppliers. Supporters of the bills said the secrecy laws were necessary for the states to continue with executions, since pharmacies and drug suppliers have refused to publicly supply drugs for executions. Opponents included the ACLU, media and first amendment organizations who said the laws would curtail public oversight of executions.

Mississippi also passed a law intended to remove obstacles to executions. The new law gives the Commissioner of Corrections unprecedented discretion in determining how prisoners will be executed. The state’s previous policy allowed prisoners to elect which method would be used for their execution. The new law places that decision in the hands of the Commissioner of Corrections, who must inform the prisoner of the method to be used within seven days of receiving an execution warrant. The law does not tell the commissioner how to determine which method to be used and provides no transparency regarding how that choice is made.

Kentucky became the second state, along with Ohio, to bar the death penalty for people with serious mental illness. The bipartisan bill prohibits the death penalty for defendants with a prior diagnosis of four serious mental health disorders: schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder, and/or delusional disorder, but does not apply to people already on death row. Defendants who qualify under the measure can still be tried and convicted, but will face a maximum sentence of life without parole.

On the federal level, President Joe Biden signed historic legislation making lynching a federal crime. The law had been proposed more than 100 years earlier. “From the bullets in the back of Ahmaud Arbery to countless other acts of violence — countless victims known and unknown — the same racial hatred that drove the mob to hang a noose brought that mob carrying torches out of the fields of Charlottesville just a few years ago,” Biden said. “Racial hate isn’t an old problem; it’s a persistent problem. A persistent problem. And I know many of the civil rights leaders here know, and you heard me say it a hundred times: Hate never goes away; it only hides. It hides under the rocks. And given just a little bit of oxygen, it comes roaring back out, screaming. But what stops it is all of us, not a few. All of us have to stop it.”

For more on the historical relationship between lynching and the death penalty, see DPIC’s November 2020 report, Enduring Injustice: the Persistence of Race Discrimination in the U.S. Death Penalty.