In a new article for the Lewis & Clark Law Review, author Carla Edmondson argues that the future dangerousness inquiry that is implicit in capital setencing determinations “is a fundamentally flawed question that leads to arbitrary and capricious death sentences” and because of the “persistent influence of future dangerousness … renders the death penalty incompatible with the prohibitions of the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments on cruel and unusual punishment.”

Edmonson’s article, Nothing is Certain but Death: Why Future Dangerousness Mandates the Abolition of the Death Penalty, reviews the pervasive influence of future dangerousness in capital sentencing decisions throughout the U.S., either as a statutory aggravating factor, or as a permissable line of argument that prosecutors may use to encourage a jury to impose a death sentence. Edmondson argues that the practice of considering future dangerousness “impermissibly asks jurors to function as fortune tellers, basing their sentencing determination on the likelihood of some future, unascertained event.” The article examines the history of the future dangerousness question, its use in various states, and empirical evidence documenting its inaccuracy, randomness, and powerful impact.

Edmonson cites seminal studies conducted in Texas and Oregon, two states in which capital sentencing juries are required to find that defendants pose a continuing threat to society before they may impose the death penalty. Those studies, she writes, demonstrate both the unreliability of expert testimony on future dangerousness and the inaccuracy of jury determinations on the subject.

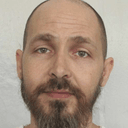

Experts in psychology have long argued that predictions of future dangerousness are junk science, and their use in capital sentencing proceedings continues to create serious constitutional concerns. On February 22, 2017, the U.S. Supreme Court overturned the death sentence imposed in Texas on Duane Buck (pictured), whose trial was tainted by racial bias when the defense’s own psychologist testified that Buck posed a future danger because he was black. On August 19, 2016, the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals stayed the execution of Jeffery Wood to permit him to litigate claims that the future dangerousness predictions of the state’s expert — who had been expelled from state and national professional associations for his unscientific and unethical future dangerousness predictions in the past — constituted false scientific evidence whose use violated due process.

“Often based on unreliable and prejudicial evidence, predictions of future dangerousness undermine the efficacy of any imposed sentence,” Edmondson argues. “Its unavoidable influence on life-or-death decisions, and the irremediableness of the problems associated with inaccurate predictions of future behavior, demonstrates why any system of capital punishment is unconstitutional and cannot be applied consistent with the Eight Amendment’s prohibition on cruel and unusual punishment.”

The 2004 Texas study cited by Edmondson examined 155 cases in which prosecution experts said capital defendants would pose a continuing risk of violence and found that the experts’ predictions of future dangerousness were wrong 95% of the time. The study of Oregon prisoners convicted of aggravated murder between 1985 and 2008 showed that “jurors’ predictions of future violent conduct appeared ‘to be completely unrelated to the actual commission of such acts’”; that “[m]ost capital offenders, whether sentenced to death or placed in the general prison population after being sentenced to life without parole or obtaining relief from a death sentence, do not commit serious acts of violence while in prison”; and that defendants who were sentenced to life, defendants who were sentenced to death, and defendants whose death sentences were reversed and were resentenced to life had virtually identical low rates of serious violence while in prison.

Carla Edmondson, NOTHING IS CERTAIN BUT DEATH: WHY FUTURE DANGEROUSNESS MANDATES ABOLITION OF THE DEATH PENALTY, Lewis & Clark Law Review, Vol 20:3, 2016.