The outcome of a capital prosecution can be predicted based upon the relative social status of the victim, the defendant, and the jurors, applying a sociology concept known as the geometrical theory of law, according to the authors of a new book, Geometrical Justice: The Death Penalty in America.

In their new book, released in the Summer of 2022, University of Denver criminology and sociology professor Scott Phillips and University of Georgia sociologist Mark Cooney apply the concept of “social geometry,” developed in the 1970s by sociologist Donald Black, to analyze outcomes of capital cases. After reviewing extensive data collected in connection with the landmark Baldus Study of capital sentencing in Georgia and from the national Capital Jury Project, they conclude that the sentencing outcomes in the cases in those databases support key principles of Black’s theory: the higher the social status of the victim and the lower the social status of the defendant, the more likely a death sentence will be imposed.

Black first introduced the concept of a “geometrical theory of law” in his 1976 book, The Behavior of Law (1976). The theory, Phillips and Cooney explain, posits that the “outcome of a case depends on its social geometry — the location, direction, and the distance of the case in social space.” Social space, put simply, is that “realm of reality humans create through interacting with one another,” and consists of five dimensions: (1) “vertical status” (i.e., wealth); (2) “radial status” (i.e., the degree of involvement in social institutions, such as family, work, religious institutions, politics); (3) “cultural status” (i.e., conventional versus unconventional social traits); (4) “normative status” (i.e., perceived respectability); and (5) “organizational status” (i.e., capacity for collective action).

The authors obtained data from two premier studies of capital punishment to perform their research. Their first dataset was an updated (2020) version of the data from the late University of Iowa law professor and social scientist David Baldus and his colleagues’ study on race and the death penalty, which formed the basis of the constitutional challenge to Georgia’s racially disproportionate application of capital punishment case in McCleskey v. Kemp in 1987. Second, they analyzed data from the National Science Foundation-funded Capital Jury Project, to examine the impact of a juror’s social status on capital sentencing decisions.

Using data from the updated Baldus study data, Phillips and Cooney coded values for defendants and victims along all five social dimensions, producing an overall status score. They found that those with the highest social status scores were “professionals (e.g. doctor, accountant), a parent supporting a child, White, had a clean criminal record, or were state officials.”

Phillips and Cooney then sought to test three key propositions of Black’s theory. First, “downward law is greater than upward law” — that is, individuals with cumulatively higher social status scores will tend to receive more favorable treatment under the law against individuals of cumulatively lower social status than low status individuals will receive against higher status individuals. Second, “law varies directly with social status” — the higher the social status the greater likelihood of favorable treatment under the law. Third, “law increases with social distance,” which means that incidents involving strangers will receive a greater “quantity of law” than incidents involving non-strangers. Applied in the context of capital punishment, Phillips and Cooney explain, a greater “quantity of law” — read as a harsher punishment — would mean a death sentence as opposed to life in prison.

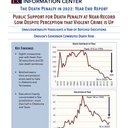

Phillips’ and Cooney’s analysis of the death penalty sentencing data produced statistically significant support for the three key propositions of Black’s “geometric justice” theory. Their comparison of the relative social statuses of victims and defendants revealed that 11% of cases involving victims of higher social status than the defendant resulted in death sentences, as compared to only one percent cases in which the victim was of lower social status. That, they said, showed that downward cases are more likely to receive a death sentence than upward cases.

In situations in which the parties were of approximately equal status, they found that death sentences involving higher status victims were more likely to result in death sentences (7% of cases) than cases involving lower status victims (1% of cases). Those results, they said, validated Black’s suggestion that “law varies directly with social status.” Acknowledging the original findings of the Baldus study, which after a regression analysis that controlled for hundreds of factors found that “the probability of a death sentence was greater in White victim cases,” the authors repeated their analysis, removing race from the measure of status. They found that without the explicit consideration of race, the “underlying pattern is the same,” that the “social status of the parties helps to predict who gets sentenced to death.” While supporting Black’s theory, the analysis did not take into consideration the impact of race in influencing each of the five dimensions of social status that went into the overall assessment of an individual’s social status.

Supporting Black’s proposition that “law increases with social distance,” Phillips and Cooney found that defendants were more likely to be sentenced to death for killing a stranger (17% of cases) than for homicides in which the victim and defendant knew one another (3% of cases).

The authors also calculated the likelihood of a death sentence based on the social status scores of the empaneled juries, using data from the Capital Jury Project. Coding nine variables to calculate each juror’s social status, they found that high status jurors were more likely to vote for death than lower status jurors.

Scott Phillips and Mark Cooney, Geometrical Justice: The Death Penalty in America (2022).