The first half of 2021 spotlighted two continuing death-penalty trends in the United States, according to the Death Penalty Information Center’s 2021 Mid-Year Review. On one hand, the continuing erosion of capital punishment in law and practice across the country; on the other hand, the extreme and often lawless conduct of the few jurisdictions that have attempted to carry out executions this year. The year began with three executions that concluded the Trump administration’s unparalleled spree of 13 federal civilian executions in six months and two days, and saw state attempts to revive gruesome, disused execution methods and to introduce never-before-tried ways of putting prisoners to death. At the same time, the first half of 2021 featured the historic abolition of capital punishment in the former home of the Confederacy and historically low numbers of both executions and new death sentences.

Virginia’s abolition of the death penalty was significant both historically and symbolically. When Gov. Ralph Northam signed the repeal bill (pictured), it was the first time a Deep South state whose death penalty was closely tied to a history of slavery, lynching, and Jim Crow segregation had abandoned the punishment. Virginia was the 23rd state to abolish the death penalty and, with formal moratoria on executions in place in three states, meant that a majority of states either did not authorize the death penalty or had a formal policy against carrying it out.

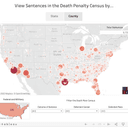

Five people were executed in the first half of the year — three by the federal government and two by the state of Texas. Only four new death sentences were imposed — one each in Alabama, California, Florida, and Nebraska — in a rate of sentencing unmatched since the death penalty resumed in the U.S. in the 1970s. The low numbers were once again unquestionably affected by the pandemic, but signaled that 2021 will be the seventh consecutive year of fewer that 30 executions and fewer than 50 new death sentences in the U.S.

The states of Arizona and South Carolina moved forward with plans to carry out executions using execution methods that have been abandoned in most of the country due to their brutality. Arizona announced that it had “refurbished” its gas chamber to execute prisoners with cyanide gas, the same substance used by the Nazis to murder more than a million people during the Holocaust. One day before the tenth anniversary of the state’s last execution, the South Carolina legislature passed a law allowing the state to perform executions using the electric chair or firing squad. Alabama announced that it was nearly ready to perform executions using nitrogen hypoxia, a new, untried method in which the prisoner dies of asphyxiation from breathing pure nitrogen.

The executing states also displayed remarkable incompetence, with South Carolina setting four execution dates it was incapable of lawfully carrying out; Arizona testing the air-tightness of its execution chamber by passing a candle flame across its seals; Nevada obtaining drugs online in probable violation of state and federal law and despite advance notice that the drugs could not be used for executions; and Texas forgetting to bring assembled reporters into the prison to witness an execution.

Death Penalty Information Center, DPIC 2021 MID-YEAR REVIEW: Virginia’s Historic Death Penalty Abolition Accompanies Continuing Record-Low Death Penalty Usage in First Half of Year, July 1, 2021.