At the midpoint of 2019, death sentences and executions remain near historic lows in the United States, with executions and pending execution dates concentrated heavily in a few southern states. The year’s executions and new death sentences have disproportionally involved defendants or prisoners with mental illness, brain damage, and/or severe childhood trauma, and those with inadequate representation. New Hampshire became the 21st state to abolish the death penalty, and California’s governor imposed a moratorium, removing the possibility of execution for everyone on the nation’s largest death row. With those actions, for the first time since the 1970s, a majority of Americans now live in states that either have abolished the death penalty or have imposed a formal moratorium on executions. Two more innocent men who were wrongfully convicted and sentenced to death – Clifford Williams Jr. and Charles Ray Finch – were exonerated, the nation’s 165th and 166th death-row exonerations since 1973. Both exonerations occurred more than four decades after the wrongful convictions.

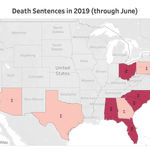

Six months into 2019, it appears that, for the fifth consecutive year, there will be fewer than 50 new death sentences and fewer than 30 executions. The Death Penalty Information Center has documented 14 new death sentences formally imposed in the first half of 2019, with eight other jury recommendations for death awaiting final judicial action. At this point in 2018, 27 new death sentences had been formally imposed. Nine states, six of them in the South, have formally imposed new death sentences, but to date no state has imposed more than two. No county has imposed more than one new death sentence.

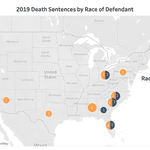

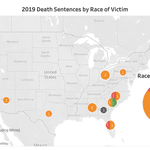

Among those sentenced to death are two defendants who waived their right to a jury trial, two who represented themselves, and one who was sentenced to death based upon a non-unanimous (10 – 2) jury recommendation in Alabama, the only state that allows such sentences. One defendant, Tiffany Moss in Georgia, has brain damage that impairs the portion of her brain responsible for impulse control, executive function, and decision-making. Nonetheless, the trial judge allowed her to represent herself at trial, where she presented no defense. She became the first person sentenced to death in Georgia since 2014. The new death sentences show continuing race-of-victim disparities, with death sentences disproportionally imposed in cases involving white victims: 10 of the 14 cases involved only white victims, and two others involved white victims along with victims of other races.

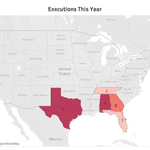

The ten executions carried out in the first half of 2019 have been highly geographically concentrated. All ten were in southern states, and more than half (60%) were in Texas and Alabama. Nine of the ten (90%) had evidence of at least one of the following impairments: brain injury, brain damage, or an IQ in the intellectually disabled range; serious mental illness; or chronic abuse and trauma. Three (30%) were younger than age 20 at the time of the offense for which they were executed. Of the 52 execution dates that have been set this year, 44% (23) have been stayed, reprieved, rescheduled, withdrawn, or rendered moot because the prisoner died on death row. Nineteen death warrants — more than one-third (37%) — are still pending. Nine of those warrants are in Texas. Four others are in Ohio, where Governor Mike DeWine has suspended executions based upon concerns that the state’s current lethal-injection method is unnecessarily torturous.

Major activities at the state level show the continuing decline in the death penalty. Death-penalty repeal bills were proposed in 17 state legislatures. New Hampshire became the 21st state to abolish the death penalty when its legislature overrode the governor’s veto of the repeal bill. It was the last state in New England to authorize the death penalty. The Oregon legislature, which cannot abolish the death penalty because it was put in place by a voter referendum, passed a bill to significantly reduce the number of crimes punishable by death. The bill is awaiting action by the governor. Chambers in three states— Ohio, Texas, and Virginia— passed bills to eliminate the death penalty for people with serious mental illness. The Virginia bill died in the House of Delegates and the Texas bill died in the Senate when neither voted on the bills before their legislative sessions ended. The Ohio bill passed overwhelmingly in the House and is currently pending in the Senate. Governor Gavin Newsom of California took the significant step of imposing a moratorium in his state, which has more death-row prisoners than any other state.

UPDATED to include death sentences imposed in Texas on June 26, 2019 and in North Carolina on April 23, 2019