More than a dozen former Alabama prosecutors, judges, and state bar presidents have filed briefs in a Birmingham court calling for a new trial for Alabama death-row prisoner Toforest Johnson (pictured, center, with family members). The extraordinary filings join Jefferson County District Attorney Danny Carr in supporting efforts by lawyers from the Southern Center for Human Rights, the University of California-Berkeley Law School Death Penalty Clinic, and the Innocence Project to free Johnson from what they regard as a wrongful capital conviction and death sentence.

Former Alabama Attorney General Bill Baxley, one of the prosecutors who is seeking to overturn Johnson’s conviction, wrote in a March 9, 2021 Washington Post op-ed, “[a]s a lifelong defender of the death penalty, I do not lightly say what follows: An innocent man is trapped on Alabama’s death row.”

“Johnson’s murder trial was so deeply flawed, the evidence presented against him so thin, that no Alabamian should tolerate his incarceration, let alone his execution,” Baxley wrote.

Johnson has continuously maintained his innocence of the 1999 murder of Jefferson County Sheriff’s Deputy William G. Hardy. No physical evidence connects Johnson to the crime and ten alibi witnesses place him at a nightclub on the other side of Birmingham when the shooting occurred. Over the course of four different court proceedings involving Johnson or his co-defendant, Ardragus Ford, prosecutors presented at least five different, conflicting accounts of how the murder occurred, based upon the shifting testimony of 15-year-old Yolanda Chambers, whom police had repeatedly threatened with imprisonment if she did not cooperate. Two other witnesses who refused to testify to the version of events police wanted were jailed.

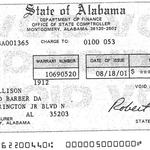

Prosecutors also presented testimony of an alleged “earwitness,” Violet Ellison, who claimed she had been eavesdropping on a phone call her daughter had placed to the prison and overheard a man calling himself “Toforest” confess to the crime. Ellison had been paid $5,000 in reward money for her testimony. Although the trial judge, Alfred Bahakel — whose brother was a Jefferson County sheriff’s deputy at the time Hardy was murdered — approved the payout and the prosecution was aware of the reward, neither disclosed the payment to the defense or to the jury.

“All of the evidence, including phone records and witnesses, clearly showed that [Chambers] couldn’t have witnessed the Hardy murder,” said Richard Jaffe, a defense attorney who represented Ford. “Her accusations should have been painfully and obviously false.” Ford ultimately was acquitted, but Johnson’s court-appointed lawyer failed to marshal the available evidence and he was convicted and sentenced to death.

“My conclusion, beyond all shadow of doubt, is that this evidence should not have gone to a jury,” Baxley told the Associated Press. “It’s not sufficient to uphold conviction. My further conclusion is that the guy is not guilty. The guy is innocent,” Baxley said.

The brief of the former prosecutors, while not addressing the question of Johnson’s innocence, urged that his conviction be overturned. “The case of Toforest O. Johnson merits thoughtful reconsideration,” they wrote. “Based on the substantial evidence supporting Mr. Johnson’s innocence and right to a new trial, it would be unconscionable not to grant a new trial.”

A brief filed by former judges of the Alabama Supreme Court and Alabama Court of Criminal Appeals and former Alabama Bar Association presidents argued that “overwhelming evidence casts serious doubts over Mr. Johnson’s conviction. To prevent a reprehensible miscarriage of justice that may otherwise lead to the execution of a likely innocent man, this Court should defer to District Attorney Carr’s recommendation and grant Mr. Johnson’s [new trial],” they wrote.

In a separate brief, the Innocence Project wrote, “[i]f ever a case bore the hallmarks of a wrongful conviction, Toforest Johnson’s is it.”

Johnson’s Family Continues to Press for Justice

Johnson’s family has long pressed his fight to prove his innocence. Johnson’s daughter, Shanaye Poole, who was five years old when her father was sentenced to death, told The Birmingham Times, “It’s tough because you miss time with your father, you miss time with your family, some of the life lessons are stripped away from you prematurely.” Her other siblings and their children, she said, feel the same. “[My father] has grandchildren he hasn’t seen aside from pictures we can send to him,” she said. “It’s been tough through the years. … I was confused as a child because I just didn’t understand, because we’re taught that justice serves us all.”

Tony Green, Johnson’s first cousin, told The Times, “I love my cousin, we grew up together, there’s only two or three years difference between us in age. … I feel they have an opportunity to make an extreme wrong right. … We can’t get the time back” that has been lost to Johnson’s wrongful imprisonment, Green said, “and we realize that, but they can do as much as they can to make this situation right by granting his freedom.”

Bill Baxley, Opinion: As a former Alabama attorney general, I do not say this lightly: An innocent man is on our death row, Washington Post, March 9, 2021; Mark Berman, Former prosecutors, judges join push for new trial in Alabama death row case, Washington Post, March 10, 2021; Bryan Lyman, 14 former judges, prosecutors urge new trial for Alabama death row inmate, citing ‘irregularities’ in conviction, USA Today, March 11, 2021; Kim Chandler, Ex-judges, others urge retrial for Alabama death row inmate, Associated Press, March 10, 2021; Erica Wright, Family of Alabama Death Row Inmate Seeks Just Mercy, Birmingham Times, February 19, 2020.

Read the amicus curiae briefs of the Alabama appellate judges and the former Alabama prosecutors.