More than forty years after he was convicted and sentenced to death by an all-white Columbus, Georgia jury for the rape and murder of a 19-year-old white woman, Johnny Lee Gates (pictured) will be getting a new trial. On March 13, 2020, the Georgia Supreme Court unanimously held that DNA contained on physical evidence that police and prosecutors had withheld for decades raised “significant doubt” as to Gates’ guilt.

The court’s 9 – 0 decision rejected an appeal by state prosecutors of a January 2019 trial court ruling that had set aside Gates’ convictions in the 1976 killing. DNA testing of physical evidence that police and prosecutors had falsely claimed no longer existed excluded Gates as the source of DNA on a bathrobe belt and several neckties that the killer had used to bind his victim. The decision was the culmination of decades of court proceedings that litigated Gates’ innocence and intellectual capacity and systemic race discrimination by the prosecution.

Gates’ 1977 conviction relied heavily on a confession that defense attorneys have long said was the product of coercive police interrogation of an intellectually disabled man. The confession, they argued, included information fed to Gates by police as well as some details that did not match the facts of the crime.

Gates’ death sentence was vacated in 2003 based on evidence of his intellectual disability. At that time, he was granted a jury trial to determine whether his intellectual impairments made him ineligible for the death penalty. When that trial concluded in a mistrial, the prosecution and defense reached an agreement to resentence Gates to life without parole.

For years, police and prosecutors claimed that no physical evidence existed that could be subjected to DNA testing. But in 2015, two Georgia Innocence Project interns reviewed the case file and discovered a manila envelope that contained the neckties and a bathrobe belt. If the prosecution’s theory of the crime — which asserted that Gates had acted alone and had been barehanded when he tied up the victim — was true, he would have left DNA from skin cells on the fabric. DNA testing showed that Gates’ DNA was not present on the items. The appeals court that, while the state’s evidence of Gates’ guilt appeared strong in the absence of the DNA results, he “could have much more effectively countered” the state’s case with the now-available DNA evidence.

Gates’ case was marred from the outset with misconduct by a prosecutor’s office that had an extensive history of racial discrimination. Gates, who is black, was tried before an all-white jury in a trial that took only three days, including the penalty phase. As early as 1991, DPIC had reported that Columbus prosecutors had regularly empaneled all-white juries against black capital defendants, including Gates. During the appeal process, Gates’ lawyers discovered jury selection notes from seven death-penalty cases tried by his prosecutors, which showed that they had systemically excluded black prospective jurors from every capital trial to empanel all-white or nearly all-white juries.

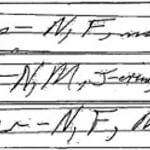

The notes showed that the state attorneys who prosecuted Gates’ case had carefully tracked the race of jurors, struck every Black juror they could, and repeatedly wrote derogatory comments about black people and black prospective jurors, describing black prospective jurors as “slow,” “old +ignorant,” “cocky,” “con artist,” “hostile,” and “fat.” White jurors were marked with the letter “W,” while black jurors were marked with the letter “N.” A Georgia Tech mathematics professor provided expert testimony that the probability that black jurors were removed for race-neutral reasons was infinitesimally small – 0.000000000000000000000000000004 percent.

In an opinion that excoriated local prosecutors for “undeniable … systematic race discrimination during jury selection,” Senior Muscogee County Superior Court Judge John Allen found that the prosecutors “identified the black prospective jurors by race in their jury selection notes, singled them out … and struck them to try Gates before an all-white jury.” However, Judge Allen denied Gates relief on the race discrimination claims, saying that Gates had not shown that his prior lawyers could not have developed the evidence of systematic discrimination.

Gates challenged that portion of the trial court’s ruling. However, the Georgia Supreme Court found it unnecessary to address the race discrimination issue “[i]n light of our determination … that the trial court did not abuse its discretion in granting Gates a new trial on the basis of newly discovered DNA evidence …. Such claim,” the court wrote, “is now moot.”

Chattahoochee Judicial Circuit District Attorney Julia Slater said her office intends to retry Gates. He will not face the death penalty in any future trial.

Tim Chitwood, After death sentence and 43 years in prison, Columbus man will get new trial in murder case, Ledger-Enquirer, March 13, 2020; Shaddi Abusaid, Inmate granted new trial in 1976 rape, murder of 19-year-old Columbus woman, Atlanta Journal-Constitution; Russ Bynum, Georgia’s high court rules DNA evidence warrants new trial, Associated Press, March 13, 2020; Ronald Tabak, REPRESENTING JOHNNY LEE GATES, 35 U. Toledo L. Rev. 603 (Spring 2004).

Read the March 13, 2020 Georgia Supreme Court opinion in State v. Gates and the January 10, 2019 order of Muscogee County Superior Court granting a new trial to Johnny Lee Gates.

For more background see: Citing Evidence of Innocence, Race Discrimination, Georgia Court Grants New Trial to Former Death-Row Prisoner, Death Penalty Information Center, January 18, 2019; Jury Notes Show Georgia Prosecutors Empaneled White Juries to Try Black Death-Penalty Defendants, Death Penalty Information Center, March 23, 2018; Gates case was one of five Columbus, Georgia death penalty cases referenced by DPIC’s 1991 report, Chattahoochee Judicial District — Buckle of the Death Belt: The Death Penalty in Microcosm (1991).