A second Muslim death-row prisoner has filed a federal civil rights lawsuit challenging Alabama’s policy of allowing only a Protestant Christian chaplain in the execution chamber. Charles Burton, Jr. (pictured), converted to Islam 47 years ago. In a complaint filed in the United States District Court for the Middle District of Alabama, Burton, who was sentenced to death in 1992, argues that Alabama’s policy violates the Establishment and Free Exercise Clauses of the First Amendment and the religious freedom amendment of the Alabama state constitution by denying non-Christian prisoners access to religious advisors during executions in circumstances in which spiritual assistance is made available to Protestant Christian prisoners. The Stanford Religious Liberty Clinic and the Alabama federal defenders office are representing Burton in his lawsuit. “In practice, inmates who share the chaplain’s faith may hold his hand and pray with him in their final moments, but that same comfort and prayer is denied to those of other denominations or faiths,” the clinic wrote in a press release announcing the suit. “This violates basic principles of religious equality and human dignity,” the clinic said.

Burton’s challenge was filed after a 5 – 4 majority of the U.S. Supreme Court lifted a federal appeals court’s stay of execution and allowed Alabama to execute Domineque Ray, another Muslim prisoner who had argued that the state’s refusal to accommodate his request to permit an imam in the execution chamber was religiously discriminatory. Overturning the fact-finding of a federal appeals court, the Court asserted that Ray had filed his claim too late and therefore was not entitled to a stay of execution. The decision in Ray’s case drew significant criticism, and less than two months later, the Court halted the execution of Texas prisoner Patrick Murphy, who raised a strikingly similar claim. Murphy, a Buddhist, challenged Texas’ policy of allowing only Christian or Muslim chaplains, both employed by the Department of Criminal Justice, to be present during executions. Texas responded to the ruling by barring all religious advisors from the execution chamber. To avoid any possibility that Alabama could say he did not timely raise his challenge, Burton filed suit before the state has set an execution date for him.

Burton’s filing emphasizes the importance of religious freedom. Alabama’s actions, the suit alleges, “violate two of the most elementary principles of our constitutional democracy, principles that the law requires to be honored even in prison: to be able to practice one’s religion free from substantial and unjustified governmental burdens and to be free from governmental discrimination based on one’s religion.” In an editorial on April 11, 2019, the Wall Street Journal supported Burton’s claim. “The death penalty ranks among America’s most divisive issues,” the editorial board wrote. “But on one point we suspect advocates and detractors agree: the right of a condemned man to have a minister of his own faith inside the execution chamber at the hour of his death.”

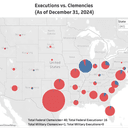

(Kelsey Dallas, Religious freedom on death row: How a new lawsuit affects a growing debate, Deseret News, April 8, 2019; Press Release, Stanford Religious Liberty Clinic Joins Legal Team in Death-Penalty Chaplaincy Case, Stanford Law School, April 4, 2019; Editorial, When a Prisoner Is Executed: Another Muslim death row inmate in Alabama pleads for an imam, Wall Street Journal, April 11, 2019.) Read the complaint in Burton v. Dunn. See Executions and Religion.