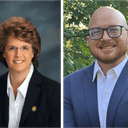

When Utah County Attorney David Leavitt (pictured) announced on September 8, 2021 that his office would no longer pursue the death penalty, his decision to do so was emblematic of a broader shift in conservative thinking on the death penalty. The Republican district attorney from “a deeply conservative” county that gave Donald Trump a 41-percentage-point margin of victory in the 2020 presidential election joined what the Wall Street Journal describes as “a growing movement of conservatives across the country pushing for an end to capital punishment.”

In a November 20, 2021 analysis, Journal reporter Laura Kusisto found that “Mr. Leavitt isn’t alone as more Republican lawmakers and prosecutors are abandoning [support for the death penalty] and champion[ing] an end to capital punishment.”

Republican “[p]oliticians and prosecutors say the shift is driven in part by concern about the cost of capital cases, which has ballooned as the appeals process has grown more extensive,” Kusisto reports. “The exoneration of dozens of death row inmates [also] has led to concern about whether the state can be trusted to decide matters of life and death.”

Leavitt, the son of a long-time Republican state legislator and brother of a three-term Republican governor, is no political radical. He cited his belief in limited government, concerns about the enormous resources required to prosecute a death penalty case, and the worthlessness of capital punishment as a crime-fighting tool. “Pretending that the death penalty will somehow curb crime is simply a lie,” Leavitt said in his policy announcement. “What I have witnessed and experienced since deciding to seek the death penalty is that regardless of the crime, seeking the death penalty does NOT promote our safety.”

The Wall Street Journal analysis places Leavitt’s decision in the context of conservative opposition to the death penalty across the country. When Virginia abolished the death penalty in March 2021, three House Republicans joined their Democratic colleagues in voting for the abolition bill. In New Hampshire, the support of many Republican legislators was necessary to override the governor’s veto and repeal the death penalty in 2019. In Ohio, a pending repeal bill was introduced by a bipartisan slate of sponsors and Utah Republican legislators have said they will be sponsoring a bill in the 2022 legislative session to replace its death penalty with a sentence of 45 years to life in prison for aggravated murder.

In 2019, the Wyoming House of Representatives approved a bill to abolish the death penalty, with the backing of a majority of House Republicans. The bill unanimously then passed the Republican-controlled Senate Judiciary Committee before it failed in the Senate, where it nevertheless drew support by 1/3 of Senate Republicans. Public opinion polls also found declining support for capital punishment in other conservative strongholds. An October 2021 Oklahoma poll reported support down ten percentage points, from 74% to 64% since 2014. A Texas poll in April 2021 reported support down twelve percentage points since 2015, from 75% to 63%. An Ohio poll, released in January 2021, found that more than half of Republican registered voters who had been provided information on innocence, costs, and other death-penalty issues favored replacing capital punishment with life without parole.

The ‘Repeal and Replace’ Effort in Utah

Leavitt’s death-penalty opposition has been echoed by other leaders in Utah. The same day he announced his office’s new policy, two Republican legislators, State Representative Lowry Snow (R – St. George) and State Senator Daniel McCay (R – Riverton) announced that they will be introducing a bill in the 2022 legislative session to repeal and replace Utah’s death penalty. Rep. Snow, a former death-penalty supporter, said his fellow Republicans have been open to his arguments for repeal. “They’ve been opposed to it, like I was before,” he said. “I’m seeing a shift in those positions.”

Republican Salt Lake County District Attorney Sim Gill, who represents the state’s most populous county, joined Leavitt and two Democratic district attorneys in supporting the repeal bill. Their endorsement was followed in October by a vote of the Utah County commissioners urging that the death penalty be repealed and replaced. Commissioner Amelia Powers Gardner pointed to the excessive financial burden of capital punishment, noting that a single capital case can cost $2 million, or about 2% of the county’s annual budget. Leavitt had raised similar concerns. His office has more than 4,000 cases to handle, he said, and a single death-penalty case required four attorneys. Other prosecutors in the office could handle as many as 125 cases. “We had spent such an enormous amount of money and resources away from the other cases we should be focusing on,” he said.

Previously, Brett L. Tolman, who served as U.S. Attorney for the District of Utah under President George W. Bush, and former Salt Lake City Police Department chief Chris Burbank joined a group of nearly 100 law enforcement leaders who wrote to the Trump administration seeking to halt the federal execution spree. “Many have tried for over forty years to make America’s death penalty system just,” their letter said. “Yet the reality is that our nation’s use of this sanction cannot be repaired, and it should be ended.”

Former Utah prosecutor Creighton Horton, who also now opposes the death penalty, summed up the change he has seen, saying that a decision like Leavitt’s would once have been “political suicide.” The recent actions of Utah officials, as well as conservative legislators in numerous other states, have shown that is no longer true.

Laura Kusisto, More Conservatives Turn Away From Death Penalty, Wall Street Journal, November 20, 2021.