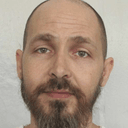

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit upheld the conviction and death sentence of a death row inmate on a tie vote (7 – 7), despite the fact that the defendant was represented by an attorney who did not even learn his client’s true name. The defense lawyer misled a reviewing court about his experience in capital cases and has been indicted for perjury. The defendant, who was tried in Kentucky as James Slaughter but whose real name is Jeffrey Leonard, is apparently brain damaged and endured a brutal childhood. A number of judges have concurred that the lawyer’s investigation into Leonard’s background was below Constitutional standards, but there were not enough votes to say that a better investigation would have made a difference in sentencing.

One of the dissenting judges, Guy Cole, sharply criticized the Court of Appeals’ decision:

We are uneasy about executing anyone sentenced to die by a jury who knows nearly nothing about that person. But we have allowed it. We are also uneasy about executing those who commit their crime at a young age. But we have allowed that as well. We are particularly troubled about executing someone who likely suffers brain damage. We rarely, if ever, allow that – especially when the jury is not afforded the opportunity to even consider that evidence. Jeffrey Leonard, known to the jury only as “James Slaughter,” approaches the execution chamber with all of these characteristics. Reaching this new chapter in our death-penalty history, the majority decision cannot be reconciled with established precedent. It certainly fails the Constitution.”

He highlighted the arbitrariness of the court’s ruling: “Although we cannot be absolutely certain that a single juror sentencing Jeffrey Leonard — a brain-damaged man whose family would corroborate his testimony and plead for his life — would come to a different conclusion, this court’s decision leaves one aspect of this case indisputable: We will never know.”

(N.Y. Times, Nov. 2, 2006; Slaughter v. Parker, 01 – 6359 (6th Cir., Nov. 1, 2006)).

See Representation and Arbitrariness.