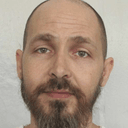

UPDATE: The Georgia Board of Pardons and Paroles denied Sallie’s request for clemency. PREVIOUSLY: Georgia plans to execute William Sallie (pictured) on December 6 in a case his attorneys argue is tainted by egregious juror misconduct that no court has considered because Sallie missed a filing deadline during a period in which he was unrepresented and Georgia provided him no right to a lawyer. It is a case that Andrew Cohen, a Fellow at the Brennan Center for Justice and long-time legal analyst, says “should shock the conscience of every person who believes [in] due process of law.” Sallie was convicted of killing his father-in-law and wounding his mother-in-law during a 1990 custody fight with his estranged wife. Because the case involved domestic violence, divorce, and a custody battle, potential jurors were questioned about their experiences with those issues in an effort to eliminate possible bias. One juror lied about her background, which included four contentious divorces, child custody and support fights, and family violence. Although the trial judge had presided over three of the juror’s four divorce proceedings — including one said to have involved dramatic scenes in the courtroom — he failed to remove her from the jury. During questioning, the same juror stated that she would follow Biblical law over Georgia law, which Cohen says also should have disqualified her from serving in the case. However, over the objections of Sallie’s attorney, the judge permitted her to serve and the Georgia courts rejected this challenge to the juror on appeal. During the course of the trial, the juror then carried on an extramarital affair with a male juror, and law enforcement personnel were dispatched to her house after the trial to tell the man his wife had been looking for him. The judge subsequently informed Sallie’s lawyers of that affair, but in the 15 months before filing a motion for a new trial, they did nothing to investigate the juror and did not raise her marital history or in-trial misconduct as an issue. The juror later said in an affidavit that she had pressured six other jurors into voting for a death sentence for Sallie. No appeals court has heard evidence of the juror misconduct because Sallie missed a filing deadline by eight days during a period when he had no lawyers representing him. Former Georgia Supreme Court Chief Justice Norman S. Fletcher decried Georgia’s failure to provide death row inmates with attorneys throughout the appeals process, saying that “[f]undamental fairness, due process and the prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment require the courts to provide an attorney throughout the entire legal process to review a death sentence. Virtually every capital-punishment state has this safeguard. Georgia is an outlier.” In his clemency petition, Sallie’s attorneys argue, “The determination of a death sentence must occur only with the most pristine and careful proceedings uncorrupted by bias and dishonesty. That simply did not happen here.”

(A. Cohen, “The Night the Lights Went Out in Georgia,” Brennan Center for Justice, December 2, 2016; R. Cook, “Death row inmate’s lawyers to Parole Board: Juror was biased,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, December 3, 2016; N. Fletcher, “Georgia’s Dangerous Rush to Execution,” The New York Times, December 5, 2016.) See Arbitrariness and Representation.