Less than a week after Alabama halted the failed execution of a terminally ill prisoner whose veins were not suitable for intraveneous injection, the U.S. Supreme Court has decided to hear the case of another Alabama prisoner whose medical condition, his lawyers say, make him constitutionally unfit for execution.

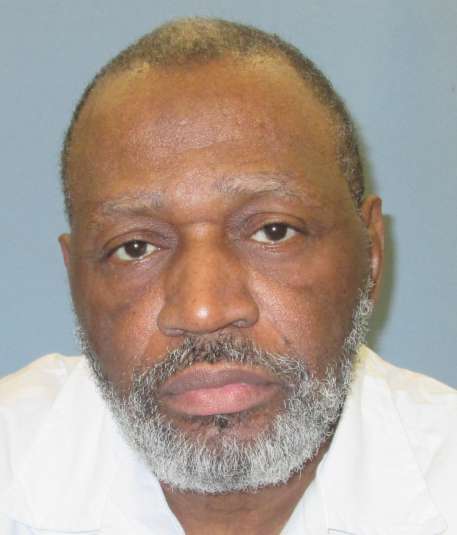

Strokes have slurred Vernon Madison’s speech and left him legally blind, incontinent, unable to walk independently, and with no memory of the offense for which he was sentenced to death. Madison’s vascular dementia, his lawyers argue, make him incompetent to be executed.

This is the third time since 2016 that Madison’s case has come before the Court. In May 2016, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit granted Madison a stay of execution to consider his competency claim. At that time, state prosecutors asked the Court to lift the stay, but with one seat vacant from the death of Justice Scalia, the Court split 4 – 4, leaving the stay in place.

Ten months later, citing uncontroverted evidence that Madison has “memory loss, difficulty communicating, and profound disorientation and confusion,” the Eleventh Circuit ruled in Madison’s favor, finding him incompetent to be executed. Alabama prosecutors again asked the Supreme Court to intervene. On November 6, 2017, the Court agreed to review the case and in a unanimous unsigned opinion reversed the circuit court’s decision.

The Court explained that, under restrictions on federal habeas corpus review of state decisions imposed by the Congress in the Anti-Terrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act (AEDPA), the federal courts were required to defer to state-court decisions under most circumstances. While expressing “no view on the merits of the underlying question outside of the AEDPA context,” the Court ruled that “the state court’s determinations of law and fact were not so lacking in justification as to give rise to error beyond any possibility for fairminded disagreement.”

Justice Ginsburg, joined by Justices Breyer and Sotomayor, concurred. However, they believed “[t]he issue whether a State may administer the death penalty to a person whose disability leaves him without memory of his commission of a capital offense is a substantial question not yet addressed by the Court.” If the issue reached the Court in an appropriate procedural posture, they wrote, “the issue would warrant full airing.”

The Court’s ruling cleared the way for Madison to be executed, and the State of Alabama set a January 25, 2018 execution date. In response, Madison’s lawyers, led by Bryan Stevenson of the Equal Justice Initiative, presented the state court with additional evidence of Madison’s deteriorating condition and new evidence that the doctor whose medical opinion had provided the court’s basis for finding Madison competent had been addicted to drugs, was forging prescriptions, and had since been arrested.

The state court denied relief without an evidentiary hearing and Madison’s lawyers — emphasizing that this was no longer a habeas corpus case — asked the Supreme Court to grant a stay of execution to review the case. On the evening of the 25th, the Supreme Court issued a stay of execution, halting Madison’s execution so it could decide whether to review his claim.

On February 26, the Court voted to review the case to determine whether the Eighth Amendment prevents a state from executing a prisoner whose mental and physical condition prevents him from having memory of the crime for which he was convicted. The Court may now review the issue unencumbered by the limitations on habeas corpus cases. The Court will likely hear argument in the fall and a decision is expected by June 2019.

Ivana Hrynkiw, Supreme Court will hear case of Alabama death row inmate, convicted of killing Mobile cop, AL.com, February 26, 2018; Supreme Court to hear Vernon Madison death penalty case, Associated Press, February 26, 2018; High Court to Review Death Penalty for Stroke-Addled Cop Killer, Courthouse News, February 26, 2018.

Read statement from Equal Justice Initiative: Supreme Court to Review Questions About Competency to Be Executed. See U.S. Supreme Court and Mental Illness.